In this present age of instability, notions of “work” never seem to stay the same. Skills, or even entire fields, may be invaluable one year and wholly disposable the next, often thanks to technological developments such as Artificial Intelligence. New economic projections by the World Economic Forum anticipate 40% of employers plan to reduce their workforce through AI-automation by 2030, with workers themselves anticipating that 39% of their existing skill set will be either transformed or obsolete.

Employment Decline and the Case for UBI

The displacement of labor has long been a basis for arguments favoring universal basic income and similar guaranteed income programs. These are typically cash assistance programs providing a basic income to cover living expenses for as broad a population as possible, often without work requirements much like the stimulus payments the U.S. government made during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Increased support for basic income and renewed attention to financial insecurity at large by policymakers is of the utmost importance given rapidly intensifying income inequality, particularly seen in the United States where there is a lower social safety net compared to other developed nations. While broad UBI programs have been increasingly prototyped in recent years, smaller targeted programs have also been introduced. Targeted income programs alongside those aimed at alleviating poverty, providing access to healthcare, social services, and retirement planning have all been adapted for a long-marginalized industry: the arts.

It may come as no surprise that financial security and careers in the arts are rarely considered together. The life of the working artist, from stage actors to painters and sculptors, is historically associated with instability, project-based work, and plenty of market risk due to a field driven by aesthetic taste. While the lucky few may experience meteoric stardom and unimaginable wealth, the data on the average artist paints a very different picture.

The Starving Artist - An Invisible Precariat

Artists in their fullest variety are already a difficult occupation to capture in data, often due to their infrequent periods of work and high rates of self-employment. Research out of the National Endowment for the Arts analyzed six federal datasets including the American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey to estimate roughly 5 million workers (artists and other labor) in the arts and cultural sectors as of 2019.

Additional research has further broken down how incomes vary among working artists. A longitudinal study of 20 million workers across industries from 2006 to 2021 found that those working as artists incur significant earnings-penalties compared to non-artists, earning upwards of 30% less than their peers depending on industry and worker demographic. (Artists in this study ranged from craft artists, singers, and musicians, to actors, art directors, and choreographers.)

The earnings discrepancy persists across education levels in a manner that would seem unintuitive to many as well: artists with undergraduate degrees in the fine arts experienced lower relative earnings than similar working artists without a bachelors, and artists with masters-level fine arts degrees earn even less than their working peers with bachelors. This makes clear a stark occupational penalty for artists as well as an educational penalty given the high cost of formal training and limited returns.

The data makes clear a reality that artists already know: The road to being a financially successful artist is narrow, risky, and unpredictable. This situation is a result of a combination of employment practices, the unique economics of the arts industry, and public policy (or lack thereof). In this way, working artists might be understood as members of the modern precariat, a socio-economic class defined by low wages, job insecurity, and poverty traps.

Their position within the precariat is not rooted in low wages alone: visual-arts workers often face long periods in their careers without employer-sponsored benefits or regular payments toward retirement funds or social security. While the performing arts have pioneered collectivist approaches to guaranteeing pensions and insurance through unions like the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA) offering such benefits, visual artists and writers working on contracts with galleries and publishing houses have been forced to be more creative in their attempts to secure such luxuries.

Guaranteed Income and Pension Programs for Artists - Potential Solutions?

Change may be on the horizon, however. An increasing number of public policies and private initiatives have appeared around the world, experimenting with schemes aimed at bolstering income and retirement security for working artists.

From a coalition of mayors advocating for guaranteed income programs to the Irish government extending a first-of-its-kind national income plan for artists, stabilizing incomes for the artistic precariat has steadily risen in prominence. The benefits of such security may go far beyond the artists themselves, with some studies suggesting that increased incomes across the board might benefit markets at large.

Universal Basic Income - A Boon for Cultural Industry

Basic income and programs may have vast implications in the arts beyond securing individual artists' livelihoods. Economist Stefan Kesenne modeled how universal basic income could stimulate both formal and informal art production, elevating arts consumption in the marketplace.

Arts organizations typically face what economist William Baumol termed a "cost disease," where their inability to increase production relative to other industries leads to rising costs without associated revenue increases. Additionally, rising incomes in the broader economy make workers' leisure time increasingly expensive, adding a "shadow price" to time-based artistic products.

Kesenne’s model demonstrated that universal basic income would increase workers' likelihood of pursuing artistic production despite potentially low payoffs due to the UBI-subsidy increasing their total income and job satisfaction. If applied broadly, cultural consumption would likely rise too as the unconditional nature of basic income reduces both direct costs and indirect costs, simultaneously increasing consumers' financial means.

The road to financial security for all, despite its grand aims, often needs to begin by attending to the most vulnerable. History reveals a steady parade of attempts at addressing the economic needs of the artists among us, providing models of successes, failure, and working drafts for policymakers today.

Historical Employment Programs in the United States [1934-1943; 1974-1982]

Source: Unsplash

Financial security comes in many forms. Stable work at a single employer is often the most common source of reliable income for the typical worker. Artists, however, often work by selling their art or labor in the form of contracts for services or through representation via galleries and dealers.

As referenced earlier, the United States saw periods of direct employment for artists through programs such as the Federal Arts Project employing some 10,000 artists on creative projects between 1935-43. The Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) further employed 20,000 artists and support staff between 1974-82, primarily in teaching and educational capacities. These two periods represent the greatest historical efforts to directly employ artists by the U.S. government.

COVID-19 and the Basic Income Wave [2020-]

COVID Measures [2020]

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted many sectors, especially the arts. In response, governments launched unprecedented assistance including stimulus checks, the Paycheck Protection Program, and Shuttered Venue Operator grants for arts organizations. Though temporary, these programs demonstrated the potential for public financial support and sparked ongoing local experiments with basic income and enhanced government assistance programs.

Guaranteed Income - Municipal Pilot Programs [2021-]

Capitalizing on pandemic relief efforts, various municipal guaranteed income programs have appeared as conversions of infrastructure established during the Pandemic, with various cities implementing pilot programs targeted specifically at artists.

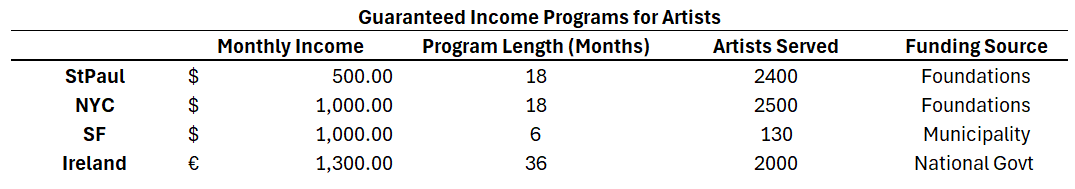

San Francisco, St Paul, and New York are three such cities. Intending to allow artists access to stable income, these programs aim to free artists from the frequent need to work second jobs for supplemental income in order to more fully focus their creative efforts and output throughout the cities.

These income experiments do not end at the municipal level, with entire nations such as Ireland enacting a three-year pilot program titled Basic Income for Artists in 2022. An additional appropriation of €35 million in 2025 will extend the program beyond its initial three-year pilot range and signals a commitment to such policies beyond pandemic-recovery contexts.

Source: Author (data from Zachary Small (NYT), CRNY, and the Government of Ireland)

The variety of such policies illustrates broad feasibility and diversity of approach, with models ranging in funding from coalitions of foundations to municipal and national government budgets serving as sources for these expenditures.

Preliminary results have shown to be promising too. A report from Creatives Rebuilding New York, the organization sponsoring the NYC program, shows that recipients of the funds were able to establish financial safety nets, pay down debt, make rent payments more reliably, and continued to create with greater flexibility in projects they could pursue and finding success in experimentation. Data showed that recipients of the funds were even more likely to win grants and prizes in support of their work than the average artist as well.

Pension-Building And Resource-Sharing: [2004-Present]

Since the turn of the millennium, attention has also shifted from artists' lack of regular employment and income to the resultant issue of access to pensions and employer contributions to retirement funds, further compounding the problems of artistic underemployment. This separate but related problem has inspired a series of organizations to build models aimed at remedying this issue. The following offer a view of private solutions both attempted and ongoing.

Source: Unsplash

Artist Pension Trust [2004-2024]

The Artist Pension Trust (APT) grew out of the bullish art market optimism of the 2000s, with its financial influences rooted in both Reaganomics and the invention of the Mei Moses Art Index in 2002. Informed by the recent discovery and promotion of art as a viable alternative asset class by researchers Mei and Moses, the APT was established in 2004 as a profit-sharing scheme whereby member artists would donate works to the trust which would then, in turn, promote the works and the artists over time. This model would reduce financial risk by diversifying its income across multiple artistic catalogues, effectively indexing the fund’s returns to the appreciation of the collective artists catalogues over time.

Unfortunately, the management of the APT ceased communications with artists in 2017 and the remaining years of the contract have been rife with scandal. Lacking accountability, the artists involved have lost any hope of retirement on this scheme and may be lucky to even get their art back.

Contemporary Art League + Commonwealth and Council - Improvements to the ATP [2021-]

The spirit of the APT, despite its failings, inspired similar efforts from various coalitions of artists determined to see the model work. Learning from the APT and even interviewing former members of the trust, a new organization called Contemporary Art League emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic intending to act as a resource bank for LA-County artists and managed by those familiar with the dynamics of the contemporary art world.

Spending a year interviewing artists about their biggest needs, they found “healthcare, childcare, and access to capital” to be the most important and lacking resources. Offering guidance on the health insurance marketplace, studio loans, and contract templates, CAL takes a more pragmatic approach to solving shorter-term inequities while advocating for greater long-term gains in public policy and equity.

Other collectivized approaches being taken by LA institutions include Commonwealth and Council, a Koreatown gallery. The Gallery created two internal programs for its artist roster in attempts to secure both healthcare as well as long-term investment returns from art.

The Commonwealth Fund, financed by collector donations in-lieu of discounts has helped contribute to artist healthcare across the gallery

The Council Trust, acting similarly to the APT, is an opt-in program where artists can donate a work valued between $15,000 and $20,000 with the profits from the pool of donated artwork being distributed to all stakeholders in the fund once sold.

Initiatives such as these show that, despite previous waves of success and failure, there is still initiative among both artists and arts managers to shed light on the financial burdens of arts workers and advocate for solutions in organizations as well as public policy.

Other Models for Artist-Support

Despite the plethora of pilot programs and established government funds committed to artist well-being, they are still a minority across the globe. While national approaches are yet to even be considered in the United States, local governments and institutions can learn from their peers how to utilize their own assets for the financial good of the artists in their communities. Structures and strategies are still developing, with further approaches and experiments adding to the collective effort toward greater financial security for artists.

Researcher Rebecca Singerman delineates three main challenges for artistic careers: unpredictability of the art market, illiquidity of artwork when considered as an asset, and dependency on galleries exposing artists to potential abuses of the relationship without protected employee benefits.

In response to these unique challenges Singerman recommends the following general measures to bolster financial security:

Smaller-scale gallery funds that support artists' financial wellbeing through regular payments, funded entirely by collectors; and

Reforms to the Internal Revenue Code and ERISA that would allow galleries and artists to contract into an arrangement wherein the gallery directly invests those payments in artists' retirement accounts.

Noticeably both suggestions embody strategies mentioned earlier, with small scale gallery funds echoing Commonwealth and Council and the tax reform evoking Germany’s KSK. This suggests that reforms throughout both industry and government might work in tandem and help mutually collaborate on shared goals.

Further outlining industry behaviors, Elizabeth Merritt of the AAM writes about reframing museums as a “Universal Basic Asset” advocating for strategic use of their physical and social capital to deliberately raise the reputations of historically marginalized artists in their collections. In partnering with the artist to exhibit, loan, and market their works, the museum would elevate the reputation of the artist, indirectly delivering gains in income and commissions, while raising the value of their own collection which would then lead to future sales to finance more acquisition-exhibition partnerships.

In this way museums could more deliberately mobilize their social capital to uplift artists and their works, delivering material, targeted returns to living artists with works in their collections. Yet again following a markets-driven model demonstrated by the APT, but managed by established arts institutions held to standard measures of accountability and oversight, having missions aligned with artists’ success and security.

Research shows how artist-endowed foundations operate in similar manners and thus could be potential sponsors of such programs as well. By attempting to preserve and develop the legacy of their founders’ works (often comprising a portion of the endowment) they therefore protect and grow the value of the foundation’s assets while subsequently dedicating their philanthropic distributions to supporting the works of other living artists and organizations in a symbiotic, market-oriented manner.

Conclusion

Artists have always struggled financially. A constellation of social attitudes, market conditions, paired with a lack of government policy and patronage have cut the artist out of a number of opportunities for financial security. From the long-term benefits of retirement and social security contributions that come with stable employment to the day-to-day needs of healthcare or a regular paycheck, such luxuries are often out of reach for the artists living next door.

While entire nations such as Germany have developed sophisticated models for including artists into their social safety nets, U.S. artists have needed to get creative and collaborate with galleries, foundations, and cities to construct solutions.

Pilot programs in cities, nations, and organizations attempting to remedy these inequities remain promising and continue to grow yearly. Whether these efforts fade as a passing political wave or strengthen into a foundation for larger-scale policies and programs remains to be seen. What can be said is that these issues are no longer being overlooked, and may indicate a renewed care toward the livelihoods of the artists among us.

-

“The Future of Jobs Report 2025,” World Economic Forum, January 7, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/digest/.

The Stanford Basic Income Lab, “What Is UBI | Stanford Basic Income Lab,” The Stanford Basic Income. accessed 2025, https://basicincome.stanford.edu/about/what-is-ubi/.

Iyengar, S., Nichols, B., Shaffer, P., Akbar, B., & Menzer, M. (2019). Artists and other cultural workers: a statistical portrait. Washington: National Endowment of the Arts.

Makridis, Christos A. “The Labor Market Returns of Being an Artist: Evidence from the United States, 2006–2021.” Journal of Cultural Economics, October 3, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-023-09490-x.World Economic Forum. “Meet the Precariat, the New Global Class Fuelling the Rise of Populism,” November 9, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2016/11/precariat-global-class-rise-of-populism/.

“AGMA Retirement and Health Fund – Take Your Benefits Center Stage,” accessed 2025, https://www.agmaretirement-health.org/.

“Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.” Accessed 2025. https://www.mayorsforagi.org/.

Newsdesk, The Hot Press. “Budget 2025: Basic Income for the Arts Scheme Extended with Funding of €35m.” Hotpress. October 01, 2024. https://www.hotpress.com/culture/budget-2025-basic-income-for-the-arts-scheme-extended-with-funding-of-e35m-23052540.

Baumol, W. J., and W. G. Bowen. “On the Performing Arts: The Anatomy of Their Economic Problems.” The American Economic Review 55, no. 1/2 (1965): 495–502.

“Linder, S. ”The Harried Leisure Class” Columbia University Press, New York (1970). https://livingeconomics.org/article.asp?docId=145.

Késenne, Stefan. “Can a Basic Income Cure Baumol’s Disease?” Journal of Cultural Economics 18, no. 2 (June 1, 1994): 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01078932.

Laning, Edward. “When Uncle Sam Played Patron Of The Arts: Memoirs Of A Wpa Painter.” AMERICAN HERITAGE. Vol 21, Issue 6. 1970. https://www.americanheritage.com/when-uncle-sam-played-patron-arts-memoirs-wpa-painter.

“CETA and Arts Employment.” 2015. https://ceta-arts.com/.

Small, Zachary. “San Francisco and Other Cities Try to Give Artists Steady Income.” The New York Times, April 6, 2021, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/06/arts/design/san-francisco-artists-income.html.

“Basic Income for the Arts Pilot Scheme,” April 5, 2022. https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/09cf6-basic-income-for-the-arts-pilot-scheme/.

Newsdesk, The Hot Press. “Budget 2025: Basic Income for the Arts Scheme Extended with Funding of €35m.” October 1, 2024. https://www.hotpress.com/culture/budget-2025-basic-income-for-the-arts-scheme-extended-with-funding-of-e35m-23052540.

Mei, Jianping, and Michael Moses. “Art as an Investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces.” The American Economic Review 92, no. 5 (2002): 1656–68.

Artnet News. “The Artist Pension Trust Had a Utopian Dream to Give Artists a Shared Retirement Fund. It’s Devolved Into Legal Threats and Despair,” January 11, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/artist-pension-trust-rise-fall-part-one-2058236.

Wagley, Catherine. “A New Generation of Idealists Is Learning From the Artist Pension Trust’s Mistakes. Can They Deliver on Its Promise?” Artnet News, January 12, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/artists-pension-trust-rise-fall-part-two-2059097.

“Commonwealth and Council,” Commonwealth and Council, February 1, 2025, https://commonwealthandcouncil.com/.

Singerman, Rebecca. “Do Artists Deserve to Retire? Methods to Remedy Disadvantages Artists Face in Saving for Retirement.” Elder Law Journal 32, no. 1 (2024): [i]-324.

American Alliance of Museums. “Sharing the Wealth: Museums as Equity Engines,” November 25, 2019. https://www.aam-us.org/2019/11/25/sharing-the-wealth-museums-as-equity-engines/.

Mischler, Lucas Lockwood. “Artists in Legacy-Land: Endowing Foundations to Balance Market and Philanthropic Activity.” M.A., Sotheby’s Institute of Art - New York, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2784392804/abstract/15ED5B8EC5B04D76PQ/1.