“Can machines think?” This was the question initially posed by Alan Turning in 1950 (Turing, 433–60). By the summer of 2024, over 2,000 artificial intelligence (AI) tools had become available to the public. While not necessarily “thinking” in the human sense, these advanced systems demonstrate capabilities that continue to blur the lines between human and machine intelligence.

The advancement of AI technologies has sparked a new wave of ethical considerations in various fields, including education. Educators, in particular, are grappling with the challenge of integrating AI into classrooms, fearing that these systems might replace traditional learning methods rather than enhance them. They might ask: Should these machines do the thinking for students?

This brings us to the following question:

What barriers prevent educators from implementing artificial intelligence into their curriculum, and how can they be addressed?

The goal is to help educators move beyond fear or hesitation toward AI while acknowledging their current concerns. While the current educational system is not adequately prepared to support AI integration, educators can, in the meantime, consider developing an AI-inclusive learning environment that maintains the integrity of the educational process.

WHAT IS AI? WHAT IS GENERATIVE AI?

AI is “a technology that enables computers and machines to mimic human abilities such as learning, comprehension, problem-solving, decision-making, creativity, and autonomy” (IBM). AI can be found within everyday applications: e-commerce, search engines, and any language translation software. AI relies on algorithms, data, and computational power to simulate human intelligence, unlike computers or smartphones.

Figure 1. The difference between a computer and an AI. Source: “What Is (AI) Artificial Intelligence?” Graphic by author.

On the other hand, Generative AI (gen AI) refers to a specific type of AI capable of producing new content, including conversations, stories, images, videos, and music (AWS). Gen AI not only generates new material but can also apply its knowledge to a variety of queries.

How Does it Work?

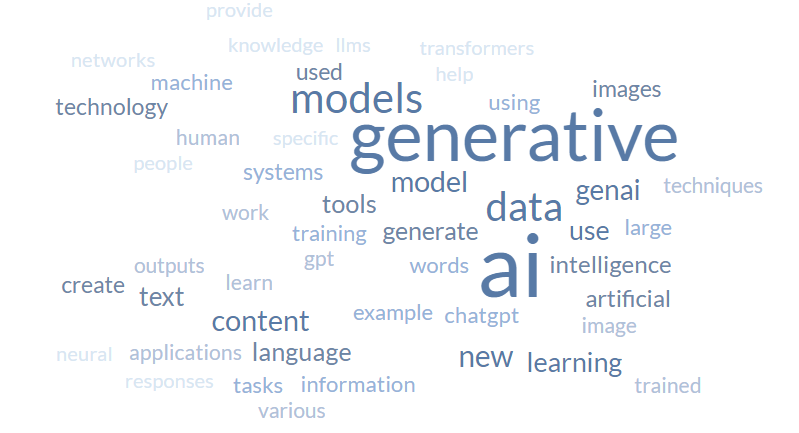

While there are many different types of generative AI models out in the world, there is a consensus on what constitutes generative AI. Among the many definitions that exist (see Figure 2), the most common reference terms include "content," "language," "intelligence," "models," "create," and "generate." According to Nvidia, generative AI uses “neural networks to identify the patterns and structures within existing data to generate new and original content” (Nvidia). Merriam-Webster defines the word generative, with regards to computing, as “using artificial intelligence algorithms to create complete units of content” (Merriam-Webster).

Figure 2. A sampling of the words used to describe generative AI. Source(s): Many. Graphic by author.

Generative AI must possess the "knowledge" to respond to queries to be labeled as artificial intelligence. For generative AI to respond accurately to queries, it must be trained to understand patterns in the data it receives. To do so, it must undergo a training process. The basic steps of that process are as follows:

Figure 3. A brief overview of how to train AI . Source: Actian. “How to Train Generative AI.”

Google provides a prompt gallery with examples of prompts to view and test. If one were to choose a prompt asking AI to sort and categorize popular Italian pasta dishes, the AI would analyze the request and generate an organized list based on its knowledge of different pasta types.

Figure 5. Google’s example AI response. Source: “Culinary Dish Classification | Generative AI on Vertex AI | Google Cloud.”

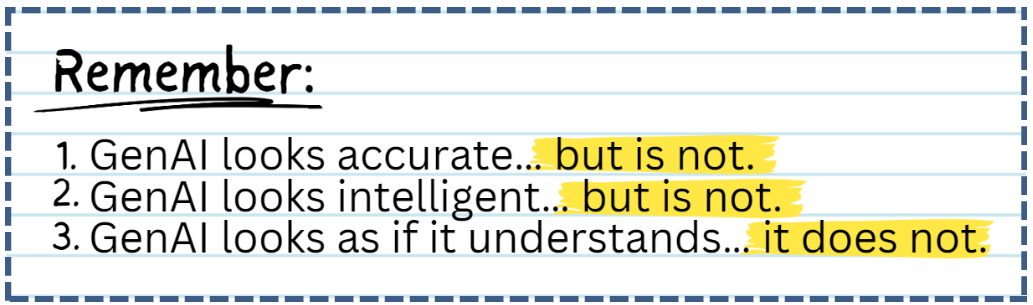

However knowledgeable generative AI might be, there are instances where queries have produced hallucinations or complete fiction. Therefore, whether you're an educator or not, it’s essential to remember that generative AI is nowhere near a substitute for research, critical thinking, or problem-solving (see figure 4 for additional reminders).

Figure 4. What to keep in mind when considering whether or not to engage with generative AI. Source: UCL, “Introduction to Generative AI.” Graphic by author.

Despite the growing global understanding of generative AI and its applications, educational spaces have yet to integrate them fully. However, some educators and schools are already exploring and implementing generative AI tools.

Current Usage of AI in Education

By Teachers

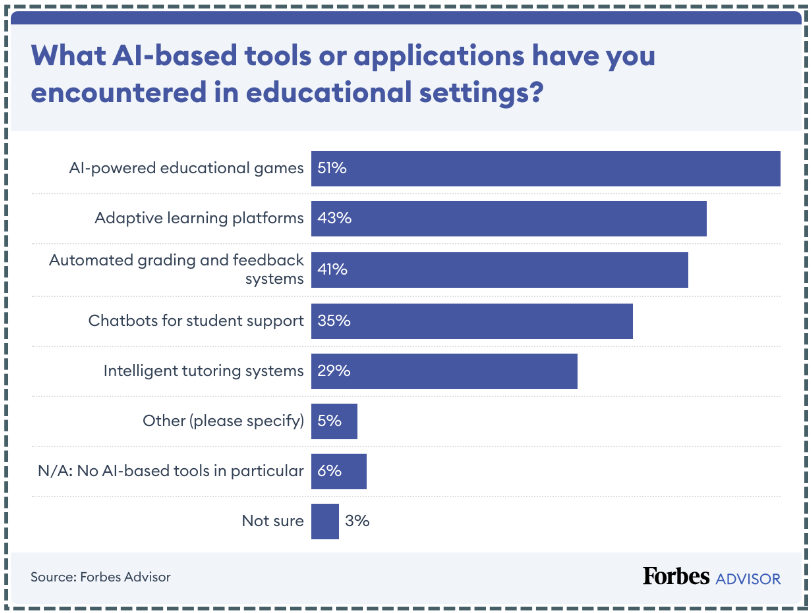

A Forbes Advisor survey of 500 educators revealed that 60% actively incorporate AI in their classrooms, with the highest usage rates reported by those under the age of 26 (Hamilton). These findings suggest that younger educators are more open to embracing AI technologies due to their familiarity with digital tools (though there exists as much evidence to support that as there is to disprove that).

Figure 5. Survey responses from practicing educators across the U.S. Source: Hamilton, “Artificial Intelligence In Education.”

That being said, a recent study from Michigan Virtual found that K-12 teachers are generally more hesitant and express concerns about using AI (Langreo). Given this divide, what exactly are the teachers who use AI incorporating it for?

AI-powered educational games are the most widely adopted AI tools in classroom settings, with 51% of educators reporting their use. Gamification has long been a popular instructional strategy for enhancing engagement and motivation. However, it’s interesting that educators use AI to design and build these games rather than creating them from scratch or sourcing them from fellow educators or online platforms. One AI tool, Taskade, specifically advertises an “AI Educational Game Generator” tool to educators seeking to “turn lessons into play” (Taskade). When prompted to create a game for a lesson plan centered around Romeo and Juliet, Taskade created an outline entirely in Spanish.

Figure 6. Taskade’s response. Source: “AI Educational Game Generator.”

These games offer innovative ways to enhance student engagement, but as the Taskade example demonstrates, AI tools are not without their quirks and limitations.

Figure 7. CoGrader’s co-founder, Gabriel Adamante, explains that this AI tool aims to work with educators. Source: “How AI Can Enhance the Grading Process.”

More successful implementations of AI can be found in tools like CoGrader, which aims to reduce grading time and assist educators in delivering personalized feedback to students. In one review of CoGrader, educator David Cutler acknowledges how a tool such as this can help him better prioritize his time and improve how he provides feedback himself (Edutopia). Adamante addresses misconceptions about the

tool's intended use (see Figure 7) and urges educators to work collaboratively with AI – both to stay informed of their students' progress and to ensure they agree with the feedback provided.

By Students

A recent study reveals that 51% of young people aged 14-22 have used generative AI, with Black and Latinx youth showing significantly higher adoption rates. However, only 4% report daily use (Harvard Graduate School of Education). While AI has made significant inroads into students’ academic lives, its use is still sporadic rather than habitual for most. The higher adoption rates among Black and Latinx youth could indicate that these groups see AI as a potential equalizer in education, or it may reflect different patterns of technology access and use among various demographic groups.

Additionally, students' most frequent use of AI revolves around writing assignments. However, in another Forbes survey, students reported also using AI for general homework questions, research support, math assistance, and help with coding (Zhang). AI has become more than a shortcut for writing tasks; it is a comprehensive aid for various aspects of learning.

Students' views on AI are also nuanced. While many believe they can be trusted to use AI responsibly, 41% acknowledge it will likely have both positive and negative impacts on their future (Harvard Graduate School of Education). Furthermore, students from Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, California, shared equally nuanced perspectives on AI in education (Ferlazzo). Their insights ranged from cautious optimism to significant concerns. Many highlighted potential issues such as AI-generated biases, the spread of misinformation, and the risk of diminishing the meaningful aspects of learning tasks. Most students recognized AI's potential benefits, emphasizing that these tools could be valuable educational assets if utilized thoughtfully and responsibly.

Barriers to AI Implementation

Despite the potential benefits to using AI, both for teachers and students, several obstacles hinder the widespread adoption of AI literacy in classroom spaces.

1. Lack of Educator Knowledge and Training. One of the primary challenges in implementing AI literacy is the gap in educators' understanding, their fear, and their lack of confidence. According to the 2024 Classroom of the Future Report, only 30% of teachers expressed moderate confidence in using AI-powered tools in their classrooms. Conversely, 45% reported being slightly to not at all confident (Clever). This significant confidence gap indicates the need for ongoing professional development and opportunities to equip educators with the knowledge to integrate AI into their teaching practices effectively.

2. Resource Constraints. While knowledge gaps persist, resource limitations also hinder AI integration in schools. The 2023 Report on School Connectivity shows that 74% of districts now have sufficient internet connectivity for daily digital learning (Ascione). However, a quarter of districts still lack adequate connectivity. Addressing these resource gaps is necessary to ensure equitable AI integration and prevent widening educational disparities.

3. Ethical and Privacy Concerns. AI tools often raise important ethical and privacy issues in the classroom. Concerns such as data privacy, the potential for algorithmic bias, and the reliance on automated systems create valid worries for educators. According to an EdWeek Research Center survey, nearly 8 out of 10 educators report that their districts lack clear AI policies. This policy vacuum leaves teachers without guidance on navigating their use and students' use of AI within their classrooms.

Conclusion: No Need to Fear

Figure 8. Quote from Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). Source: “How Technology Is Reinventing K-12 Education.” Graphic by author.

AI's role in education is rapidly expanding, whether or not educators feel fully prepared for its integration. As the use of AI technology rises in prevalence, education systems (and the educators within them) should be prepared to adapt. Moving forward, educators’ areas of focus should include:

1. Educators should take active roles in advocating for and developing AI literacy programs. One example is the Classroom-Ready Resources About AI For Teaching (CRAFT) initiative from Stanford Graduate School of Education. CRAFT aims to help high school teachers across all subjects integrate AI-related topics into their curriculum. This program supports teachers in fostering students' exploration and critical thinking about AI use. A better-informed educator can better inform students about how to engage appropriately with AI.

2. Establishing ethical guidelines for AI use in educational contexts. Educators must be advocates for their (and their students’) interests. For instance, the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction has created a framework called "Ethical Considerations for AI: A Framework for Responsible Use" (Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction). This guidance provides specific considerations for various stakeholders, including educators, students, and administrators. This framework emphasizes a human-centered approach to AI integration, with the goal that AI use in education always begins with human inquiry and ends with human reflection.

There is no one answer to approaching this issue. But, by addressing these areas, educators, students, and the systems surrounding them can begin to work toward AI's potential while mitigating its risks. Ultimately, the goal must be to create learning environments that are not only technologically advanced but also ethically sound and pedagogically effective.

-

Actian. “How to Train Generative AI.” https://www.actian.com/how-to-train-generative-ai/. “AI in Education: A Comprehensive AI Framework and Resources,” June 20, 2023. https://michiganvirtual.org/resources/ai/.

AIPRM. “AI in Education Statistics · AIPRM,” July 11, 2024. https://www.aiprm.com/ai-in-education-statistics/.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. “What Is Generative AI? - Gen AI Explained - AWS.” https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/generative-ai/.

Ascione, Laura. “Majority of Districts Now Meet FCC’s School Internet Connectivity Goal.” eSchool News, January 3, 2024. https://www.eschoolnews.com/it-leadership/2024/01/03/school-internet-connectivity-data/.

Cantú Ballesteros, Lorenia, Urías Maricela, Sebastián Figueroa-Rodríguez, and Guillermo Salazar-Lugo. “Teacher‘s Digital Skills in Relation to Their Age, Gender, Time of Usage and Training with a Tablet.” Journal of Education and Training Studies 5 (March 28, 2017): 46. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v5i5.2311.

Clever. “New Survey: AI Optimism Soars Among Teachers Amidst Demands for More Inclusive Edtech.”https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-survey-ai-optimism-soars-among-teachers-am idst-demands-for-more-inclusive-edtech-302234777.html.

CRAFT. “CRAFT Is Empowering Students with AI Literacy.” https://craft.stanford.edu/.

“Culinary Dish Classification | Generative AI on Vertex AI | Google Cloud.” https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/prompt-gallery/samples/extract_culinary_ dish_classification.

“Definition of GENERATIVE.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/generative.

Edutopia. “How AI Can Enhance the Grading Process.” https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-ai-grading-tools-enhance-process/.

Enterprise AI. “What Is Gen AI? Generative AI Explained | TechTarget.” https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/generative-AI.

Fahmiyah, Indah, Ika Qutsiati Utami, Ratih Ardiati Ningrum, Muhammad Noor Fakhruzzaman, Angga Iryanto Pratama, and Yohanes Manasye Triangga. “Examining the Effect of Teacher’s Age Difference on Learning Technology Adoption Using Technology Acceptance Model.” AIP Conference Proceedings 2536, no. 1 (May 19, 2023): 020013. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0123943.

Ferlazzo, Larry. “Here’s What Students Think About Using AI in the Classroom.” Education Week, June 19, 2023, sec. Technology, Classroom Technology. https://www.edweek.org/technology/opinion-heres-what-students-think-about-using-ai-in-the-cla ssroom/2023/06.

“Gamification and Game-Based Learning | Centre for Teaching Excellence.” https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/catalogs/tip-sheets/gamification-and-game-b ased-learning.

“Generative Artificial Intelligence | Center for Teaching Innovation.” https://teaching.cornell.edu/generative-artificial-intelligence.

Google Cloud. “Generative AI Prompt Samples | Generative AI on Vertex AI.” https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/prompt-gallery.

Google Cloud. “What Are AI Hallucinations?” https://cloud.google.com/discover/what-are-ai-hallucinations.

GovTech. “Teachers Worry About What AI May Do to Student Mental Health,” March 29, 2024. https://www.govtech.com/education/k-12/teachers-worry-about-what-ai-may-do-to-student-ment al-health.

Grose, Jessica. “Opinion | What Teachers Told Me About A.I. in School.” The New York Times, August 14, 2024, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/14/opinion/ai-schools-teachers-students.html.

Hamilton, Ilana. “Artificial Intelligence In Education: Teachers’ Opinions On AI In The Classroom.” Forbes Advisor, December 5, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/education/it-and-tech/artificial-intelligence-in-school/

“How Many Generative AI Tools Are There? A Comprehensive Guide,” June 4, 2024. https://artsmart.ai/blog/how-many-generative-ai-tools/.

“How Many Generative AI Tools Are There? A Comprehensive Guide.” https://artsmart.ai/blog/how-many-generative-ai-tools/.

“How Technology Is Reinventing K-12 Education.” https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2024/02/technology-in-education.

“Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence in Schools.” Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. https://ospi.k12.wa.us/student-success/resources-subject-area/human-centered-artificial-intellig ence-schools.

IBM Research. “What Is Generative AI?,” February 9, 2021. https://research.ibm.com/blog/what-is-generative-AI.

Langreo, Lauraine. “Teachers Are More Wary of AI Than Administrators. What Would It Take to Change That?” Education Week, January 26, 2024, sec. Technology, Classroom Technology. https://www.edweek.org/technology/teachers-are-more-wary-of-ai-than-administrators-what-wo uld-it-take-to-change-that/2024/01.

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Explained: Generative AI,” November 9, 2023. https://news.mit.edu/2023/explained-generative-ai-1109.

NVIDIA. “What Is Generative AI?” https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/glossary/generative-ai/.

Saripudin, S, Ida Budiyanto, Reni Listiana, and Sarip Udin S. “666 -680 Digital Literacy Skills Off Vocational School Teachers.” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 16 (February 1, 2021): 666–80.

“Schools Are Taking Too Long to Craft AI Policy. Why That’s a Problem.” https://www.edweek.org/technology/schools-are-taking-too-long-to-craft-ai-policy-why-thats-a-pr oblem/2024/02.

Schubert, Carolyn. “Research Guides: Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education: AI and Ethics.” https://guides.lib.jmu.edu/AI-in-education/ethics.

Shaw, Ben. “Research Guides: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Information Literacy: What Does AI Get Wrong?” https://lib.guides.umd.edu/c.php?g=1340355&p=9880574.

“Students Are Using AI Already. Here’s What They Think Adults Should Know | Harvard Graduate School of Education,” September 10, 2024. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/usable-knowledge/24/09/students-are-using-ai-already-here s-what-they-think-adults-should-know.

Taskade. “AI Educational Game Generator.” https://www.taskade.com/generate/education/educational-game.

“Teachers Growing More Confident With Using Tech in the Classroom – MeriTalk State & Local.” https://www.meritalkslg.com/articles/teachers-growing-more-confident-with-using-tech-in-the-cla ssroom/.

TeachingTimes. “Rise In Teacher Confidence Using Edtech - A Key Benefit From Lockdown,” July 16, 2020. https://www.teachingtimes.com/new-research-into-staggered-school-returns/.

Topics | European Parliament. “What Is Artificial Intelligence and How Is It Used?,” April 9, 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20200827STO85804/what-is-artificial-intelligen ce-and-how-is-it-used

Turing, A.M.. “I.— Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Mind LIX, no. 236 (October 1, 1950): 433–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

Tweed, Stephanie Renee. “Technology Implementation: Teacher Age, Experience, Self-Efficacy, and Professional Development as Related to Classroom Technology Integration,” n.d. UCL. “Introduction to Generative AI.” Teaching & Learning, August 15, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/generative-ai-hub/introduction-generative-ai.

“What Is (AI) Artificial Intelligence? | Online Master of Engineering | University of Illinois Chicago.” https://meng.uic.edu/news-stories/ai-artificial-intelligence-what-is-the-definition-of-ai-and-how-d oes-ai-work/.

“What Is AI Model Training and Why Is It Important?” https://www.oracle.com/artificial-intelligence/ai-model-training/.

“What Is Artificial Intelligence (AI)? | IBM,” August 9, 2024. https://www.ibm.com/topics/artificial-intelligence.

“What Is ChatGPT, DALL-E, and Generative AI? | McKinsey.” https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-generative-ai.

Zhang, Tao. “Council Post: The Use Of AI In Education: Understanding The Student’s Perspective.” Forbes.https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2024/07/01/the-use-of-ai-in-education-understanding-the-students-perspective/.