As the pandemic presses on, building stronger online communities can help arts organizations serve the immediate needs of all audience members now and increase access to art and community for audience members who prefer to participate from home in the future. Arts organizations are finding myriad creative ways to produce and deliver content online. However, audiences do not just come for the content; they also come for the connection. In fact, according to LaPlaca Cohen’s 2020 study Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis connection to others remains one of the most-missed aspects of arts experiences during the pandemic.

In a November article for AMT Lab, I outlined the history of third place theory and its utilization by city planners and arts managers alike to create physical spaces that facilitate the type of connection and community that arts audiences crave. This second article will help arts managers pivot from theory to action by projecting the benefits and limitations of online third places demonstrated by video game research; presenting the data supporting the urgency and viability of online third places as solutions for audience “connection”; and suggesting four platforms through which arts managers might build their organizations’ online third places.

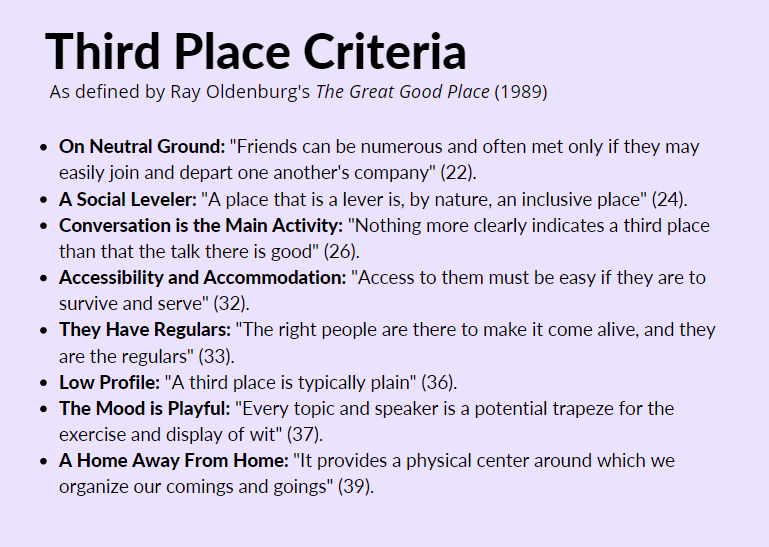

Figure 1: Third place illustration based on Oldenburg's The Great Good Place. Source: Author.

Third Places in the Online World: What We Know from Video Game Research

The term “third place” was coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in 1989 with his book The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. In his book, Oldenburg emphasizes the personal and societal value of spaces outside of work or home that center conversation and foster a true sense of community (Figure 1). Even in the analog world, not all public spaces are third places. Rather, Oldenburg lays out specific criteria, as shown below in Figure 2, for what makes public spaces effective “third places.”

Figure 2: Third place criteria as defined by Oldenburg's The Great Good Place. Source: Author.

The Great Good Place describes third places in explicitly physical terms, and Oldenburg has maintained skepticism that the third place phenomenon can be replicated online; however, researchers of massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) have found evidence that most third place attributes can indeed be found in these online spaces. Though social dynamics of video games have been studied for decades, in the mid-2000s, several ethnographies and case studies specifically and carefully analyzed the potential for MMOs to create online “third places.” Several of these studies were published in peer-reviewed journals, and all of them landed on similar conclusions. Namely, despite some drawbacks discussed later, MMO-embedded “virtual” third places functioned as socially leveling, playful, and accessible spaces for conversation just as well as or better than Oldenburg’s in-person third places.

In The Great Good Place, Oldenburg argues that socially leveling, lively, and lighthearted conversations are crucial for third place function (26), and these types of conversations were found to be common in MMO third place studies. In their 2006 paper published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication entitled “Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) Name” (a nod to the show Cheers set in a very third place-like local bar), authors Constance A. Steinkuehler and Dmitri Williams noted from their ethnographies of MMOs that “individuals with diverse worldviews found themselves interacting on a level playing field” (902). The observed interactions also consistently met Oldenburg’s criteria of playfulness. Steinkuehler and Williams observed that “the introduction of seriousness is typically met with teasing and cajoling in order to return the group to a more playful and casual state” (899). Similarly, in their article “Virtual ‘Third Places’: A Case Study of Sociability in Massively Multiplayer Games,” authors Nicolas Ducheneaut, Robert Moore, and Eric Nickell’s found the number of “joyful utterances” from Star Wars Galaxies players within the game’s cantinas (Figure 3) to be “almost exactly as upbeat as Oldenburg’s minimum standard” (150), which Oldenburg estimates to be roughly 15 laughs per hour (52). These examples clearly demonstrate the potential for virtual third places to meet many of Oldenburg’s conversational criteria.

Figure 3: Screenshot of Star Wars Galaxies cantina. Source: Medium.

These MMO third place studies also noted how virtual third places can perhaps even outperform physical spaces in another key area of Oldenburg’s criteria: accessibility. Steinkuehler and Williams noted that video game communities were “accessible directly from one’s home, making them even more accommodating to individual schedules and preferences” (894). The caveat, of course, is that online access is not without its own challenges. In his article “Computer-mediated communication as a virtual third place: building Oldenburg’s great good places on the world wide web” in the journal New Media & Society, Northern Colorado University’s Charles Soukup reminds readers that “computer-mediated environments are far from accessible to ‘anyone and everyone’” citing racial divides in internet access as well as potential issues of language barriers and hardware cost barriers (428). Still, the potential for virtual third places to reach some populations not best served by one single physical space remains.

The biggest skepticism about the function of online platforms as third places comes from limitations of the platforms themselves, particularly the absence of some neutral ground characteristics like flexible, proximity-based chance interactions with others. Much like non-place-based platforms like social media or chat platforms, older MMOs presented “no way to move away from the ‘noise’ of the main floor to a quieter alcove or backroom, for instance” (Ducheaneat et al. 158). This sort of platform-enforced inflexibility is the same reason our pandemic favorite, Zoom, isn’t a third place and is a factor in why many find Zoom so exhausting. People want the opportunity to move around, see new sights, and talk to new people.

However, since the bulk of this research was conducted nearly 15 years ago, newer games and online platforms have addressed some of these proximity-based issues related to Oldenburg’s neutral ground criteria and created positive results in their users. In one pandemic favorite, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, players can have spontaneous interactions with real-life or game-originated friends, gather around for some music (Figure 4), or even invite friends to enjoy art collections. Animal Crossing’s casual, life-based play has also had a notably positive psychological impact on many of its players during the 2020 period of social isolation. The game has been called everything from “extremely soothing” to a pandemic “lifeline” for people struggling with anxiety and depression, to, in true third-place fashion, "a game that you visit, like your local Zen garden—and villagers are out catching rays.” In many ways, the story of Animal Crossing may be the best example of what organizations and audiences might stand to gain from building high-quality, virtual third places for the arts.

Figure 4. Animal Crossing friends gather for music. Source: NME.

The Audience’s Need for Connection

If video games provide an example of how virtual third places in the arts might function, then data on the role of connection in the arts experience demonstrates why building virtual third places might be beneficial, perhaps even crucial, to arts audiences now and in the future. As lobbies remain closed, virtual third places that mimic lobby-like environments can help fill the gap created by virtual-only programming and remain as an alternate space for interaction once the pandemic subsides.

Arts audiences crave connection as a part of their arts experiences. LaPlaca Cohen’s Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis indicates that 65% of respondents miss cultural activities’ ability to facilitate “spending quality time with family or friends.” During the pandemic, 53% of LaPlaca Cohen’s respondents participated in some sort of digital cultural activity, and 49% voiced desire for arts and cultural organizations to help them “stay connected” during this time. Current audience priorities are not dissimilar from pre-pandemic audience priorities either. In LaPlaca Cohen’s Culture Track ’17 report, 56% of respondents identified that “connecting with my community” was a motivator for cultural participation, while “social” was the most-identified “characteristic of an ideal cultural activity.” This data serves as a clear call to action for arts managers to find routes for audiences to connect right now and in perpetuity. In other words, pandemic or not, the audience need for connection through art remains.

Figure 5: Data from research survey on connection via online platforms. Source: Author.

Additionally, despite general societal skepticism about the quality of communication online, users have noted the efficacy of some online platforms for connection. In a survey conducted for this research, 95.7% of respondents said they felt “a connection with the people (friends, family, community members, users)” while using an online platform in 2020 (Figure 5). Respondents were asked to specifically think of platforms outside of social media. Some (41.7%) even formed new relationships with people through solely using online platforms (Figure 6). Additionally, in a recent article for CNN, users of the platform Gather (discussed later) noted that the platform has helped them feel “more together now, sometimes, than we were before” with colleagues. Similarly, University of Pennsylvania students shared in an article in The Daily Pennsylvanian that Gather has “kept us close despite being spread out around the world.” While online connection may not be ideal, online connection, especially in times of great need, is both possible and effective.

Figure 6. Survey data on the formation of new relationships over online platforms in 2020. Source: Author.

Looking forward, given that many patrons engaging with digital content are new, online third places can help retain patrons who might not be willing or able to walk through the doors once Covid-19 subsides. Before the pandemic, two of the top three barriers to cultural participation as noted by LaPlaca Cohen’s Culture Track ’17 were “it’s not for someone like me” and “it’s inconvenient.” The 2020 version of this study speaks to how these barriers can, in part, be addressed by perpetual digital content and community offerings. In La Placa Cohen’s Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis, 55% of 2020 digital theater content consumers had not visited a physical theater in the past year, and data was similar for digital consumers of other art forms: 40% for art museums and 36% for classical music. LaPlaca Cohen CEO Arthur Cohen commented on this phenomenon in a September 2020 CI to Eye podcast interview with Capacity Interactive’s Erik Gensler: “if there have been perceived obstacles to participating as a physical experience, which are generally because you don't feel included or invited, don't see people like you participating, don't think it's for you…these are all threshold fear drivers,” then suggested that “they seem to dissipate online." LaPlaca Cohen data paired with Cohen’s comments illustrate how maintaining digital content and community connections after the pandemic can help maintain access for audiences who experience these barriers.

Respondent quotes from Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis also demonstrate how online platforms expand arts accessibility. Comments included: “I’m disabled, so even COVID-19 aside, I appreciate digital access to cultural explorations I might not otherwise have,” and “I was able to participate in activities that I might not be able to afford financially.” A third respondent noted their hope for continued online accessibility in the future by sharing “I hope this kind of creativity in access and availability grows in non-pandemic times.” While these quotes were pulled from questions about digital content, the above data about connection suggests that audiences might have similar sentiments towards pairing digital arts content with virtual third places to enhance their experiences.

“I hope this kind of creativity in access and availability grows in non-pandemic times.”

From Data to Action: Tools for building Virtual Third Places

If you are ready to act on building a virtual place for your audiences, there’s good news: several tools for doing so are user-friendly and relatively affordable. While there are myriad platforms that could theoretically serve as virtual third places for arts organizations, three promising options based on Oldenburg’s third place criteria are Gather, Mozilla Hubs, and High Fidelity. All of these platforms center conversation, are easy-to-use (accessible), and provide neutral ground where users can come and go from conversations by moving around the virtual space. Given these features, all of them can create space for playful, casual conversation that research shows is possible in the online world. Though there is evidence that some arts organizations are already starting to experiment with these platforms, colleges, weddings, conferences, and other groups have widely utilized them with mostly positive reviews. The platforms, however, have slightly different defining features and, thus, likely different use cases for different audiences and organizations.

Gather

Gather (sometimes also called Gather.town) is perhaps the most widely used of the three platforms and has become a popular event-hosting choice for colleges (including Carnegie Mellon University) and even weddings. In Gather, users can click a link to enter, choose a customizable avatar, type their name, and be walking through the space within one minute. Like real life social spaces, users can see who is in the room, but they cannot hear conversations or see user videos until they move closer to others (Figure 7). Gather provides several different template rooms—such as lounges, beer gardens, and lecture halls—that you can choose from, but you can also customize your own—perhaps to replicate a real-life lobby. Gather is also the only platform of the three that simultaneously incorporates video and audio. Some reviews note that Gather’s 2-D graphics are not particularly impressive, but Gather’s visual simplicity also adds to its charm and intuitiveness. One couple who chose to host their wedding in Gather noted that even the oldest members of their party could easily navigate the platform. Gather is also free for up to 25 guests and offers straight-forward pricing for additional capacity and features. Thus, if you are seeking a simple, affordable virtual third place platform that allows for both audio and video, Gather is worth a try.

Figure 7: Carnegie Mellon University students meet in a Gather "lounge." Source: Author.

Mozilla Hubs

Mozilla Hubs has many of the same features as Gather, but Hubs uses 3-D spaces and avatars rather than 2-D graphics and video. Though Mozilla Hubs also allows you to instantly create a room based on a template, it has also been used to host highly-customized events such as an October 2020 architecture conference. Hubs also allows users to enter through a link, and users are then prompted to choose their avatar before moving into the 3-D virtual rooms via their computer or by connecting a VR headset. Users can also embed 3-D objects in the space, which makes it particularly promising for arts organizations. In fact, a quick search of “Mozilla Hubs arts” returns several public Hubs arts galleries and festival spaces including one called “Area for Virtual Art” (Figure 8). Hubs rooms are public and free to use with no capacity limit; however, customizable, fully secure spaces for business are also available through the paid Hubs Cloud version. If customizable 3-D space is a priority, Mozilla Hubs is the tool to try.

Figure 8: Area for Virtual Art space in Mozilla Hubs. Source: Author.

High Fidelity

Finally, High Fidelity maintains all the proximity-based features of Gather and Mozilla Hubs, but boasts high-quality audio that “simulates acoustic reality” as the distinctive feature. When listening through headphones, High Fidelity’s spatial audio technology creates a sort of 3-D audio experience, where others’ voices are heard based on their location and proximity relative to the listener. Much like other platforms, users enter High Fidelity spaces through a link, then choose a display name and photo (if they wish) before entering the space. Unlike Gather and Mozilla Hubs, the space that High Fidelity offers through its free beta version is 2-D and not customizable, but the default space is neutral enough to serve a wide variety of organizations, as seen below in Figure 9. High Fidelity also accommodates up to 20 people for free, but paid versions can accommodate up to 120 people. Again, High Fidelity’s best feature is its audio quality, so it is best suited for applications where audiences may value audio over video or 3-D features offered by other platforms.

Figure 9: Layout of High Fidelity beta default space. Source: Author.

Gather, Mozilla Hubs, and High Fidelity all offer interfaces that serve audience connection in much more dynamic ways than a simple live chat function beside a livestream. With minimal effort, arts managers can create virtual third places that allow audiences to see and hear each other—and even meet new people—in many of the same ways they might in the lobby before or after a show.

Figure 10: Virtual Third Place Platforms: A Comparison. Source: Gather, Mozilla Hubs, High Fidelity, and Author.

Conclusion

In his interview on Capacity Interactive’s podcast CI to Eye, LaPlaca Cohen CEO Arthur Cohen says of virtual arts experiences: “I think we're just learning that this is another type of social experience that our brains are a little bit catching up with. It's not without its challenges and fatigue, but it is a really important point of connection." Cohen’s sentiments sum up well what we know from video game research, what data from LaPlaca Cohen and other sources say about audiences’ needs for connection, and what arts organizations stand to gain from moving not just the art, but also the interaction, online.

Though no virtual platform can perfectly replace the organic community built by in-person interaction, virtual third places, built with Oldenburg’s criteria in mind, might create something similarly joyful and uniquely accessible to connect arts communities in times of pandemic-driven social isolation and beyond.

Resources

“Area for Virtual Art.” Mozilla Hubs. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://hubs.mozilla.com/tPmdd5H/area-for-virtual-art/.

Capacity Interactive. “A Massive Survey about the Arts in 2020 America: Arthur Cohen.” CI to Eye. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://ideas.capacityinteractive.com/ci-to-eye-podcast-episodes/a-massive-survey-about-the-arts-in-2020-america-arthur-cohen.

“Capacity Upgrade Request | High Fidelity Beta Release.” High Fidelity. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.highfidelity.com/online-audio-space-capacity-upgrade.

Chang-Yi Zawacki, Selina, and Sarah Waldorf. “How to Build an Art Museum in Animal Crossing.” The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty (blog), April 16, 2020. https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/how-to-build-an-art-museum-in-animal-crossing/.

Collins, Ang. “Animal Crossing’s Low-Stakes Domesticity Is a Soothing Balm for Stressed Millennials.” The Guardian, April 1, 2020. http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/apr/02/animal-crossings-low-stakes-domesticity-is-a-soothing-balm-for-stressed-millennials.

Coup, Brett. “Virtual Poster Session with Gather.Town - Carleton College.” Carleton College Academic Technology Blog (blog), November 13, 2020. http://www.carleton.edu/academic-technology/blog.

Ducheneaut, Nicholase, Robert Moore, Eric Nickell, Barry Brown, and Louise Barkhuus. “Virtual ‘Third Places’: A Case Study of Sociability in Massively Multiplayer Games.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 16, no. 1 (April 2007): 129–66.

Fairs, Markus. “Space Popular Designs World’s First Virtual Architecture Conference.” Dezeen (blog), November 3, 2020. https://www.dezeen.com/2020/11/03/space-popular-worlds-first-virtual-architecture-conference/.

Forney, E. “Virtual Spaces for Realistic Learning.” Carnegie Mellon University. Accessed November 2, 2020. https://engineering.cmu.edu/news-events/news/2020/10/27-cee-gather.html.

“Gather.” Accessed October 20, 2020. https://gather.town/.

“Gather Pricing.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://gather.town/pricing.

“Get Ready for Virtual Halloween with Mozilla Hubs.” The Firefox Frontier (blog). Accessed December 6, 2020. https://blog.mozilla.org/firefox/virtual-halloween-mozilla-hubs.

“Hard Questions: Is Spending Time on Social Media Bad for Us? - About Facebook.” Accessed October 17, 2020. https://about.fb.com/news/2017/12/hard-questions-is-spending-time-on-social-media-bad-for-us/.

Hayden, Scott. “‘High Fidelity’ Shifts Focus Towards Non-VR Due to Slow Growth.” RoadTOVR, April 17, 2019. https://www.roadtovr.com/high-fidelity-shifts-focus-towards-non-vr-due-slow-growth/.

Henley, Stacy. “How to Create Your Own Music Festival in ‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons”.” NME (blog), May 29, 2020. https://www.nme.com/guides/gaming-guides/how-to-create-music-festival-animal-crossing-new-horizons-2678218.

High Fidelity. “Host Your Event in High Fidelity.” YouTube, July 2, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8n-wbjex8ak.

High Fidelity. What If Zoom Had Spatial Audio? Youtube, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWsPvzw5Z8M&feature=youtu.be&__hstc=207334796.338d826cd7664412fd375a33db6dba92.1607272747383.1607272747383.1607272747383.1&__hssc=207334796.1.1607792675292&__hsfp=2686683400&hsCtaTracking=1b0834fc-1ff6-4b2f-9d82-63f1932aa20d%7C998ab4ef-9159-4099-9fd9-1ea94f60ee00.

“How to Add Friends in Animal Crossing: New Horizons.” Digital Trends. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/how-to-add-friends-animal-crossing-new-horizons/.

“Hubs by Mozilla.” Accessed December 6, 2020. https://hubs.mozilla.com/.

“Hubs Cloud.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://hubs.mozilla.com/cloud.

Eventbrite. “Inside the Wild Heart - Streaming through Gather Town.” Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.eventbrite.com/e/128779993427?aff=efbneb.

Khoury, Keely. “Barcelona Architecture Conference Held in Virtual Reality,” Springwise, November 17, 2020. https://www.springwise.com/innovation/work-lifestyle/space-popular-virtual-architecture-conference.

King, Darryn. “The Unbearable Lightness of Animal Crossing.” Wired, April 8, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/unbearable-lightness-animal-crossing/.

LaPlaca Cohen. “CCTC Interactive Tool.” Culture Track, 2020. https://culturetrack.com/cctc-interactive-tool/.

LaPlaca Cohen. “Culture + Community in a Time of Crisis.” LaPlaca Cohen, July 7, 2020. https://s28475.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CCTC-Key-Findings-from-Wave-1_9.29.pdf.

LaPlaca Cohen. “Culture Track ’17.” LaPlaca Cohen, 2017. http://s28475.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CT2017-Top-Line-Report.pdf.

Lee, Isaac. “Penn Students Use Digital Platform Gather to Imitate In-Person Office Hours.” The Daily Pennsylvanian, October 22, 2020. https://www.thedp.com/article/2020/10/gather-town-penn-cis-virtual-office-hours.

Lewis, Rachel Charlene, Marina Watanabe, Alison Vu, and Roslyn Talusan. “‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons’ Is the Perfect Quarantine Video Game.” Bitch Media. Accessed December 6, 2020. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/how-animal-crossing-helps-with-mental-health.

Matsakis, Louise. “Zoom Not Cutting It for You? Try Exploring a Virtual World.” Wired, May 5, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/zoom-not-cutting-it-virtual-world-online-town/.

Metz, Rachel. “Forget Zoom: You Can Do Meetings on a Website That Looks like a Retro Video Game.” CNN, October 6, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/06/tech/gather-zoom-video-game-chat/index.html.

Muncy, Leah. “Animal Crossing: New Horizons Review 2020.” New York Magazine, December 3, 2020, sec. The Strategist. https://nymag.com/strategist/article/animal-crossing-new-horizons-review.html.

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. Da Capo Press, 1989.

High Fidelity. “Online Audio Spaces for Groups and Crowds High Fidelity.” Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.highfidelity.com.

Russell, Anna. “Zoom Fatigue and the New Ways to Party.” The New Yorker, September 17, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/zoom-fatigue-and-the-new-ways-to-party.

Schultz, Ryan. “Comparing the New High Fidelity with Online Town and Gather: ‘Choices!’” Ryan Schultz: News and Views on Social VR, Virtual Worlds, and the Metaverse, May 25, 2020. https://ryanschultz.com/2020/05/25/comparing-the-new-high-fidelity-with-online-town-and-gather-choices/.

Skarredghost. “Mozilla Hubs Review: A Completely Open and Free VR Social for the Web.” The Ghost Howls (blog), April 27, 2018. https://skarredghost.com/2018/04/27/mozilla-hubs-review-a-completely-open-and-free-vr-social-for-the-web/.

Soukup, Charles. “Computer-Mediated Communication as a Virtual Third Place: Building Oldenburg’s Great Good Places on the World Wide Web.” New Media & Society 8, no. 3 (June 2006): 421–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444806061953.

Steinkuehler, Constance A., and Dmitri Williams. “Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) Name: Online Games as ‘Third Places.’” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11, no. 4 (July 2006): 885–909.

“Third Places in Culture - Ray Oldenburg Q&A.” Steelcase. Accessed September 24, 2020. https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/topics/design-q-a/q-ray-oldenburg/.

University, Carnegie Mellon. “THE Virtual FAIR - Student Leadership, Involvement, and Civic Engagement - Division of Student Affairs - Carnegie Mellon University.” Accessed December 12, 2020. http://www.cmu.edu/student-affairs/slice/involvement/the-fair.html.

Webb, Kevin. “‘Animal Crossing: New Horizons’ for the Switch: What We Know so Far.” Business Insider, June 13, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/animal-crossing-new-horizons-nintendo-switch-release-date-2019-6#up-to-eight-player-characters-can-live-on-the-same-island-and-four-people-can-play-new-horizons-at-once-using-the-same-switch-if-youre-playing-online-you-can-have-eight-players-exploring-the-same-island-at-once-2.

“What Is a Third Place?.” Forge America. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.forgeamerica.com/blog/2015/12/3/what-is-a-third-place.