Introduction

The notion of individual liberty in the United States is directly tied to the level of autonomy one holds in making decisions and exercising free speech in the real world. Considering that the lines delineating the real world and that which exists in a digital space are increasingly becoming blurred, having a concrete understanding of the policies relating to the usage of one’s personal data as well as the potential effects that the storage of data profiles can have on citizens in a democracy is essential for artists and activists to operate freely. In many scenarios, both domestically and abroad, a digital expression of one’s beliefs can be easily sought after by both public and private entities because bulk data harvesting has become so commonplace. Whether artists create content digitally or use digital spaces to exhibit their art and promote their messages, if the content isn’t entirely neutral, it may be subject to unwanted oversight.

Domestically, the internet currently allows for the free expression of ideas by citizens of the United States, whether through mass social media platforms or less popularized ones, under both the First Amendment and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which protects internet companies from being held liable for their users’ content. These platforms function as “town squares” in which people have the ability to practice public discourse as a democratic right. Public discourse can be exhibited both verbally or through artistic expression in person and can be done anonymously if proper precautions are taken by the artist and/or activist. But, in the digital world, true anonymity is not easy to come by unless the user has the technical knowledge to remain anonymous.

Deliberating on potential regulatory frameworks and preexisting laws regarding privacy and intellectual property can occur through many structures and perspectives. Lawmakers, in international spheres and on the federal and state levels, are generally guided by ideological lines on what is or is not appropriate to censor. As such, this research is centered around the question:

“What should artists who use internet platforms as a public forum expect regarding the privacy of their data and the potential both private companies and governmental entities have in censoring or using their work? ”

The Importance of a Virtual “Town Square”

Public spaces provide opportunities to demonstrate against state values or actions, but as society inches farther into the information age, and as society develops digital alternatives to socializing (largely because of pandemic-related restrictions and the addictive qualities of social media), more demonstration may occur digitally rather than in person. Much of the time, artists tend to act and ask for forgiveness afterwards if the message is presented through the lens of freedom of expression laws (this can be the case in in many Westernized nations). As testament to this, in Australia, racial inequalities are extremely prevalent, and civil disobedience has undoubtedly increased awareness of the “fear-state” propagated by the suppression of protestors practicing civil disobedience through performative art or more direct demonstration (McQuilten 2019).

The emergence of social distancing measures due to the Covid-19 pandemic has proven that demonstrating in a public space, whether in the form of protest or artistic expression, is not as viable as it once was. Even though physical protests still occur, the potential for a future where performative art and activism exist almost solely in a virtual space is undoubtedly plausible. Citizens need to be afforded public spaces in a democracy since these spaces allow for, nearly, unconditional debate on topics of public importance.

In the broadest sense, public discourse, in person, is a tool average citizens have used for centuries to voice their own opinions, while simultaneously leaving the floor open for opposition. In these scenarios, if a person hopes to stay anonymous, there are easy protections one could take to increase the chance of staying anonymous. Because bulk data retention has become normalized in digital spheres, however, there is far less of a chance for the average citizen to voice concern about public issues online without having documented digital proof of these acts saved in server farms.

The guise of surveillance as a necessary security tool allows for governing bodies to designate the “time, place, and manner” reasonable for protest groups to assemble (Starr et al. 2008). Within these parameters, activists still protest, and similarly, performative artists will still exhibit their artistic messages, which allows for an extension of ideology without being required to put a face to the cause, if the artist so chooses. Relatedly, there are a wide range of possibilities as to how U.S. state or federal governing bodies could similarly police the digital assembly of protest or artistic expression posed against the state, but in these instances, due to an inherent lack of digital privacy on many internet platforms, individuals have less of a chance to demonstrate without the expectation of direct governmental oversight.

Domestic Data Privacy Legislation

While legislation regarding the collection and security of individuals’ data is essential to maintain a safeguarded flow of information, both in private and public sectors, without a standardized view of the needs of citizens as people (as opposed to the characterization of a citizen as a consumer), the fragmented landscape will continue to fragment, and with it, a collective understanding of what precedents should be newly set before censoring ideas, concepts, digital posts and the like.

California’s Proposition 24

Domestic privacy laws vary state by state, but California’s recent passage of Proposition 24 (a.k.a. the California Privacy Rights Act of 2020), which will amend aspects to the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 regarding the state’s citizens digital privacy, is considered to be the reference point by which other state legislators could base their decisions. The enactment of this proposition is expected to have varying effects on internet users after it becomes operative on January 1, 2023, though it is not clear, in practice, how or when these effects will occur. More specifically, the American Civil Liberties Union expects that some technology or social media companies may begin charging users subscription costs or increased subscription costs if they choose to prevent the website from saving their personal data for the purpose of selling it to advertisers, but this is only based on speculation at the moment. However, it is clear that California internet users who take advantage of this development will immediately be able to navigate across digital platforms without expecting the unchecked sale and sharing of their personal data, if they so choose.

While the passage of this proposition may not immediately have a direct impact on independent digital artists and activists, because individual internet users will have the chance to “opt out” of the sale and sharing of their personal data, there would be less of a chance for either bad actors, law enforcement officials or potential authoritarian regimes to be able to access personal information. Another protection enabled under the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) called the “Right to Restrict Use of Sensitive Personal Information” makes the tracking of individual users more difficult as consumers may limit the use of “precise geolocation data, race, religion, sexual orientation, social security numbers, and certain health information outside the context of HIPAA.” This allows for an even higher potential of anonymity for internet users, but could pave way for the necessity of internet-based companies to exist by the direct monetary payment of users as opposed to the ad-based models many companies use today.

The EARN IT Act

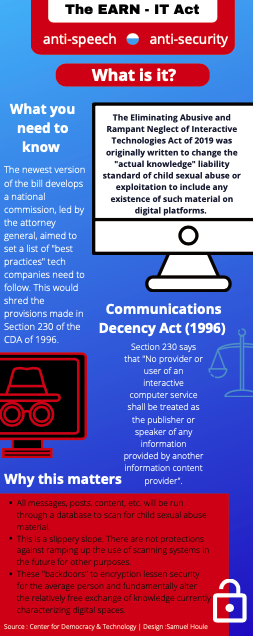

Figure 1: EARN IT Act infographic. Source: Author.

American policymakers have quietly passed the EARN IT Act (Eliminating the Abusive and Rampant Neglect of Interactive Technologies Act of 2020) through the Senate Judiciary Committee and have released an amended version to the House to be voted on. This version provides an optional “best practices” standard, which will be determined in the future by a national commission of 19 individuals, chaired by the attorney general. Its passage would push internet-based companies to lessen the potential for liability in scenarios when the company’s users post content that could have a linkage to child sexual abuse material (CSAM) by either adhering to the designated “best practices” or following specific state guidelines. While it is no debate that child sexual exploitation should always be condemned, online or elsewhere, the degradation of current encryption standards (that occurs by adhering to the “best practices” standards or that which would be outlined on a state-by-state basis) by the implementation of “backdoors” for law enforcement, on both the state and federal level, means this front does not come without a clear price to the privacy of American citizens, especially in the long term. Putting this amount of power into the hands of tech giants is not in the public’s interest, and even Brad Smith, chief legal officer and president of Microsoft, believes that there should never be democracies which ”cede the future to leaders the public did not elect” (Smith and Browne 2019). Without a comprehensive solution, tech elites may increasingly become the judge, jury and executioner regarding what is and is not acceptable in society—digitally or elsewhere.

Social Media Companies as “Agents of the Government”

Considering that the execution of the EARN IT Act would push social media companies to more aggressively target content with algorithms—designed to flag postings or messages with any relation to CSAM—and decrease the already -ow standards of privacy regarding user profiles, these private entities would functionally become “agents of the government” due to the legal precedent set in Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Association. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that the necessity of proper care and management of railways “justified a departure from standard warrant and probable-cause requirements in searches.” In reference to this scenario, the stipulations set under the EARN IT Act would allow for the search and seizure of content that would otherwise be considered unlawful because of the notion of a “special need.” The transformation from a solely private entity to one with “the Government’s encouragement, endorsement, and participation” in the search for CSAM would insinuate that any evidence gained through algorithmic scanning would not be admissible in court without a warrant, due to the Fourth Amendment. If the government, at either the federal or state level, chooses to accept the evidence without a warrant, the question of unconstitutionality arises. This points to the notion that the EARN IT Act’s main purpose is not solely combatting online child sexual exploitation, but to press forward in lessening end-to-end encryption of private entities.

It is for these reasons that more than 50 private, civil privacy-related organizations have denounced this bill. In the context of artistic expression, because there is no one, set legal guideline for how the breaking of current encryption standards would only be utilized for the purpose of combatting online CSAM, digital activists who use art as a tool to practice dissidence towards the state, digital artists, and artists who use internet platforms to document and spread awareness of their messages could very well be subject to scrutinization by controlling government entities. These government entities could be from various levels of the bureaucracy, and decisions could be split among all 50 state legislatures. This fragmentation would only further entrench an individual state government’s ability to define the acceptability of certain concepts, from what is “obscene” or not to even what forms of content should be flagged under the umbrella of national security.

Additionally, the form of algorithms that would be used for the purpose of content moderation, as they exist currently, are not equipped to consistently, effectively, and fairly parse apart flagged content and acceptable content. Even current Facebook anti-nudity filters wrongly interpret certain images as pornography. A recent mishap in the filtering process led a digital photograph of three onions to be flagged as “overtly sexual.” While this specific instance was harmless, future occurrences of false flagging may condemn users even if they are innocent or have no harm in mind when posting or messaging on the internet, especially if censorship were to ramp up because of ideological pressures.

Investigative journalism has always been a hotly contested topic amongst tech elites since its mere existence adds potential to the level of scrutiny both governmental officials and industry giants come into contact with due to their decisions and impact on the transfer of information in society. Mark Zuckerberg signed off on a change in algorithmic processing at Facebook in 2017 that led to a decrease in web traffic flow to left-leaning news sites. Mother Jones, one such left-wing news source, reportedly had increased costs (in the hundreds of thousands range) because of this decision and has made clear that they believe this was a deliberate attack on factual digital reporting. Art as a tool of dissidence closely relates to the sentiment behind some forms of investigative journalism as the proponents of both tend to react to ideological pressures of the state. If the EARN IT Act would force social media companies, such as Facebook, to increase algorithmic oversight of its content, individuals like Zuckerberg could, in turn, have even more of an effect on free expression.

A Comparison of International Digital Privacy

The concern of digital privacy is ubiquitous around the globe. As testament to this, the Communist Party of China, the state authority governing the People’s Republic of China, has been eliminating dissidence through direct government action. These officials are continuing to gain more control to characterize information on digital platforms in such a way that increases the potential for suppression of conflicting ideologies between the citizens of China and the government. For instance, “China’s Provisions on Ecological Governance of Online Information Content” is now in effect, which is a set of provisions that allows for information spread by internet content creators to be specifically categorized as “illegal” or “negative,” among other draconian designations.

Internet governance in China, as it currently stands, is a prime example of state-enforced knowledge control. The very existence of independent content creators is seen as a threat to the outlined basis of what Xi Jinping and other officials believe the internet should represent as a pillar of societal interaction, interstate communication, and other transfers of information (Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies 2018). Legislation is also currently being drafted for a stricter national security law in Hong Kong. The provisions within the legislation would have “internet service providers, telecommunication operators, those who manage social networks and online platforms, and potentially those operating the numerous data centers in Hong Kong” face higher levels of censorship to shield themselves from the liability of their users. This same sentiment is tied to legislation in the U.S., although not necessarily to the same degree. Regardless, it is clear that global scrutiny towards citizens’ digital presences is wholly increasing.

The European Union lies at the forefront of collective governance, relating to digital privacy, that attempts to put citizens’ personal rights over that of economic growth. The political and social sentiment around the collection of individuals’ data largely differs from that of China and the U.S. The enforcement of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) shows that EU lawmakers are aware that the scope of commercial data use from internet platform users is too vast for any one person to be aware of all that is occurring (Ausloos 2020). As such, the right to erasure is far more prevalent and accepted in the EU, which gives more freedom to its citizens in their digital presence. In tandem with this, bulk data retention was also recently ruled as illegal.

However, in the EU, there are still strict guidelines centered around copyrighted material on digital platforms. While the protection of intellectual property is essential in the designation of personal rights to opinion and creation, the future may hold even harsher laws towards violators, even if the violation is accidental. Memes were exempt within the passage of these laws, which does allow for a fair level of freedom of expression, but many experts claim the protections currently set in place are not sufficient and could be subject to change in the future. This could ultimately impact aspects of the free exchange of information that currently is characteristic of the internet.

These cases of internet governance by foreign states shed light on the legislative extremes that exist within major tech economies. In any country, digital privacy protections are essential to level the playing field for those acting against state interests for positive change. More specifically, because criminal data records can be relatively easily procured if needed, those who are arrested for something once could still be impacted even if they are not charged, especially if there are not protections against the length of time certain data can be saved digitally, such as that which is listed within California’s Proposition 24. Considering that private social media companies may now need to act with more state oversight, the potential for the misuse of data and user-generated content in the sphere of law enforcement is high, and with this trend, the possibility for false or unconstitutional arrests is also higher than in the past. Without setting a functional legal precedent to guide these instances of content moderation and censorship, the trend is likely to continue as the surveillance state becomes further entrenched into society.

If an artist were to be arrested for public art against the state but not charged, this could still impact their livelihood. Similarly, this could occur in a digital space as well. While, for example, China and the United States’ governments are fundamentally different in principle, there are still domestic state actors with agendas that are in complete opposition to any forms of civil disobedience. In line with this notion, a recent change in policy within the U.S. State Department has citizenship-seekers provide their social media accounts in their application, which insinuates that any postings the federal government deems unacceptable could hinder the path to citizenship. This would force artists who use social media to self-censor in fear of alienation or state scrutiny, even if there is nothing inherently illegal about their digital content and/or views.

The Scope and Effects of Misinformation and Media Bias

Misinformation in the digital age is rampant and detrimental to society in a number of ways, but one of—if not the most noteworthy aspect to this sentiment—is that the act of misinforming usually occurs along ideological lines, which means left, right, and centrist viewpoints must coexist under the First Amendment in digital spaces, even if certain viewpoints are not factually backed; it is left up to the decision-makers and owners of these internet platforms to determine what is and is not acceptable to post or message. Herein lies the dilemma of the pervasive influence of social media companies, because stricter control over hate speech, for instance (through any medium, such as text posts, memes, videos, etc.), would arguably lessen the impact of, per se, systematic racism, to a degree, but could also pave way to setting a dangerous precedent that could equally impact other forms of positive civil disobedience on the opposite end of the spectrum. For instance, hate speech defined by a more left-leaning Supreme Court would likely differ largely from that which would be defined under a right-leaning Supreme Court. This is not to say that hate speech shouldn’t be moderated by companies directly, but unless the people react negatively towards companies who fail to effectively moderate hate speech, a mandate from the governmental level is not going to necessarily solve anything; there must be both bureaucratic and public support. Private entities, such as arts management organizations, should also take strong stances towards effective content moderation that occurs without an expectation of a loss of digital privacy. Most digital users have been tricked into believing these concepts are mutually exclusive.

Alternative Routes to an Impactful Digital Presence

Until a collective, standardized digital privacy effort occurs on both the state and federal level, with foreign cooperation, both artists and activists should be careful where and how they post their content digitally. Even though landmark precedents have previously been set and are prominently known—such as the decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) in which Justice Brennan wrote that there is a “profound national commitment that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials”—the emergence of governmental officials blocking forms of free speech online is at an all-time high. Without updating the legality around such issues, this issue will only snowball.

Because Facebook has such a comparative monopoly on user data to all, if not most other, competing social media companies, there are huge barriers to entry, which is why Facebook is so hotly contested in anti-trust talks. However, this factor does not insinuate it is impossible for those with a message—digital political organizers, activists, and artists who operate along ideological or political lines—to reach others. What this concept does mean is that these individuals must begin to more consciously choose where and how they place their message, be it textual or visual, until domestic data privacy laws are fully, or at least reasonably, user-first. If an artist continues to present politically divisive topics online, they should expect a digital trail to follow. The cost of increasing personal privacy in today’s digital landscape is one’s access to the masses.

To mitigate the harms of internet usage as an artist, there are alternatives that currently allow for a more secure and de-commercialized exchange of ideas on the internet. One such alternative is Telepath, which is similar to Twitter in that it has a scrolling feed, but different in that Telepath has specific guidelines related to concepts like kindness, fake news, and content moderation. If users would be allowed to relinquish the hold tech companies have on the usage of their data, and if internet users would start to shift away from social media outlets that already have mass collections of their data, the potential for censorship would be relatively low in comparison, as long as the users chose to follow the stipulations set by the moderators. Digital content will always be overseen by an entity, but it is up to individuals to choose whether a public or private entity is more effective and fairer in doing so. Until a secure standard is set, artists as individual consumers of digital platforms must begin to take matters into their own hands.

Resources

Ausloos, Jef. The Right to Erasure in EU Data Protection Law : from Individual Rights to Effective Protection New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Azarmi, Mana, and Hannah Quay-de La Vallee. "The New EARN IT Act Still Threatens Encryption and Child Exploitation Prosecutions." Center for Democracy and Technology. October 05, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://cdt.org/insights/the-new-earn-it-act-still-threatens-encryption-and-child-exploitation-prosecutions/.

Batycka, Dorian. "Art and Creative Acts That Were Censored in 2019." Hyperallergic. January 31, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/534808/art-and-creative-acts-that-were-censored-in-2019/.

"California Proposition 24: New Rules for Consumer Data Privacy." CalMatters. October 08, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://calmatters.org/election-2020-guide/proposition-24-data-privacy/.

Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies. China Internet Development Report 2018 Blue Book of World Internet Conference 1st ed. 2020. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020.

Cook, Sarah. "How to Watch for Freedom Disappearing in Hong Kong." Foreign Policy. June 24, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/24/freedom-disappearing-hong-kong-china-national-security-law/.

Edelman, Gilad. "The Fight Over the Fight Over California's Privacy Future." Wired. September 21, 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/california-prop-24-fight-over-privacy-future/.

Friese, Stephanie. "Pondering Public Art? Legal Concerns and Artists Rights Are Part of the Palette." NAIOP Commercial Real Estate Development Association. 2018. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://www.naiop.org/Research-and-Publications/Magazine/2018/Winter-2018-2019/Development-Ownership/Pondering-Public-Art-Legal-Concerns-and-Artists-Rights-are-Part-of-the-Palette.

Geiger, Gabriel. “The European Court Just Ruled That Bulk Data Retention Schemes Are Illegal.” VICE, October 6, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en/article/bv89aa/the-european-court-just-ruled-that-bulk-data-retention-schemes-are-illegal.

Harris, Dan. "China's Glorious New Internet Censorship: What a Beautiful World This Will Be." China Law Blog. March 18, 2020. Accessed November 08, 2020. https://www.chinalawblog.com/2020/03/chinas-glorious-new-internet-censorship-what-a-beautiful-world-this-will-be.html.

H.R. Doc. No. Congressional Research Service-R45631 at 3 (2019). "Data Protection Law: An Overview."

Hudson, David L., Jr. "'A Profound National Commitment' to 'Robust' Debate." Freedom Forum Institute. December 16, 2019. Accessed December 04, 2020. https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/2019/12/16/a-profound-national-commitment-to-robust-debate/.

Hutnik, Alysa Zeltzer, Aaron Burstein, and Carmen Hinebaugh. "It's Here: California Voters Approve the CPRA." Ad Law Access. November 04, 2020. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://www.adlawaccess.com/2020/11/articles/its-here-california-voters-approve-the-cpra/.

Jibilian, Isabella. "Mark Zuckerberg Reportedly Signed off on a Facebook Algorithm Change That Throttled Traffic to Progressive News Sites - and One Site Says That Quiet Change Cost Them $400,00 to $600,000 a Year." Business Insider. October 19, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-mark-zuckerberg-throttled-traffic-to-progressive-news-sites-wsj-2020-10.

Kang, Cecilia. 2020. "FTC Decision on Pursuing Facebook Antitrust Case is Said to be Near." New York Times, Oct 22. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/2453518290?accountid=9902.

Kleinman, Zoe. "Article 13: Memes Exempt as EU Backs Controversial Copyright Law." BBC News. March 26, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-47708144.

McQuilten, Grace. “Who Is Afraid of Public Space? Public Art in a Contested, Secured and Surveilled City.” Art & the public sphere 8, no. 2 (December 1, 2019): 235–254.

Morar, David, and Bruna Martins Dos Santos. "The Push for Content Moderation Legislation around the World." Brookings. September 21, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2020/09/21/the-push-for-content-moderation-legislation-around-the-world/.

Morrison, Sara. "California Just Strengthened Its Digital Privacy Protections Even More." Vox. November 04, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/11/4/21534746/california-proposition-24-digital-privacy-results.

Mullin, Joe. The EARN IT Bill Is the Government’s Plan to Scan Every Message Online.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. October 1, 2020. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/03/earn-it-bill-governments-not-so-secret-plan-scan-every-message-online.

Ohlheiser, Abby. "How the Truth Was Murdered." MIT Technology Review. October 13, 2020. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/10/07/1009336/how-the-truth-was-murdered-disinformation-abuse-harassment-online-2/.

Perez, Sarah. "Hands on with Telepath, the Social Network Taking Aim at Abuse, Fake News And, to Some Extent, 'free Speech'." TechCrunch. October 11, 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://techcrunch.com/2020/10/11/hands-on-with-telepath-the-social-network-taking-aim-at-abuse-fake-news-and-to-some-extent-free-speech/?utm_source=American Alliance of Museums&utm_campaign=92eb52b10d-Dispatches_October15_2020&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f06e575db6-92eb52b10d-37342201.

Robitzski, Dan. "Facebook Algorithm Flags Onions as "overtly Sexualized"." Futurism. October 06, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://futurism.com/the-byte/facebook-algorithm-flags-onions-overtly-sexualized.

Rodriguez, Salvador. "Facebook Is a Social Network Monopoly That Buys, Copies or Kills Competitors, Antitrust Committee Finds." CNBC. October 07, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/06/house-antitrust-committee-facebook-monopoly-buys-kills-competitors.html Links to an external site.

Smith, Brad, and Carol Ann Browne. Tools and Weapons. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2020. http://web.a.ebscohost.com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzIwMzc1NzhfX0FO0?sid=342014bc-d32b-4452-add1-e7050151ac09@sessionmgr4008&vid=0&format=EK&rid=1. page 296

Starr, Amory, Luis A. Fernandez, Randall Amster, Lesley J. Wood, and Manuel J. Caro. "The Impacts of State Surveillance on Political Assembly and Association: A Socio-Legal Analysis." Qualitative Sociology 31, no. 3 (2008): 251-70. Accessed October 20, 2020. doi:10.1007/s11133-008-9107-z.