How effectively are art museums actually providing neurodiverse accessibility, if at all? What strategies can be implemented to enhance inclusivity for neurodiverse visitors and support educators who aim to bring neurodiverse students into these spaces? Part One of this research offered background on what neurodiversity is, why museums should address it, and how to design a museum for neurodiverse accessibility.

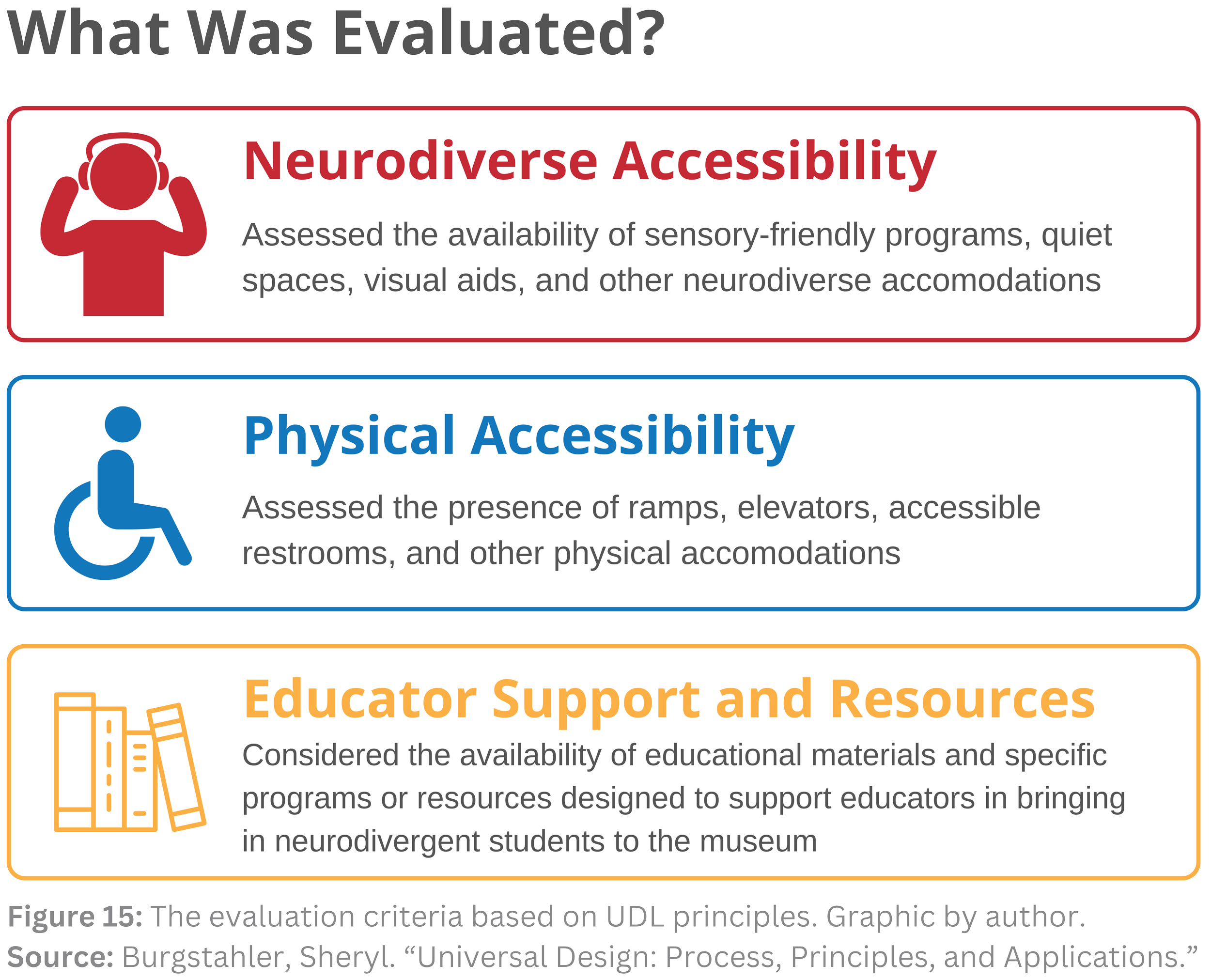

To better understand how art museums are addressing neurodiverse audiences, an evaluation was conducted of 30 Art Museums in three areas: neurodiverse accessibility offerings, physical accessibility offerings, and educator support and resources. showing that museums are still falling short of universal levels of accessibility.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY: HOW ARE ART MUSEUMS PERFORMING?

In an effort to understand how art museums are addressing neurodiverse audiences, I conducted my research utilizing the American Alliance of Museums database, specifically searching for art museums listed under the art museums/centers/sculpture gardens category. From the initial 738 results, 214 were disqualified as they were not typical field trip destinations for educators; these included gardens, airport galleries, and university-affiliated museums. From the final count of 514 art museums, 30 museums were randomly selected for analysis.

As depicted in Figure 14, the randomly selected art museums were well-distributed across the U.S., with some sparsity noted in the central and northern regions. Using the finalized list of art museums, further analysis involved examining each art museum’s website from the perspective of a school teacher looking for a suitable art museum to visit with a group of students, including those who are potentially neurodivergent. In particular, this process focused on the art museums’ homepage, the “plan your visit” page, and any dedicated sections or web pages that covered accessibility, educational resources, and field trips.

The criteria for grading each art museum focused on three main areas: neurodiverse accessibility offerings, physical accessibility offerings, and educator support and resources. The scoring system for these criteria was straightforward—each museum could earn points based on receiving a positive (3 points), partial (2 points), or negative (1 point) score, with a maximum possible score of 9 points.

Based on these individual scores, the total score for each art museum was then categorized into one of three levels (see figure 16). The scores were also impacted by how readily this information was available and if the websites were accessible. Again, taking into consideration how a teacher might approach this process.

In addition to the information accessible via each art museums’ website, additional factors were analyzed. These included:

The geographic location of each art museum, whether rural, urban, or suburban, was analyzed to understand if there was a correlation between location and accessibility measures.

The employee count of each art museum was recorded to assess if the quantity of staff helped towards facilitating a comprehensive, accessible experience.

Similarly, the number of staff members holding education-related positions or having “education” in their job title was analyzed.

Lastly, information regarding art museums' budgets were gathered from their FY22 Form 990's in order to determine whether a smaller, or larger, budget had any influence on museums’ accessibility.

The end goal was to comprehensively evaluate whether or not art museums within the U.S. were successfully providing well-rounded accessibility resources. In addition to this, examining all potential factors affecting the ability of an art museum to provide, or fail to provide, an inclusive and equitable experience to all visitors.

FINDINGS: MUSEUMS ARE… NOT QUITE THERE

The findings unveiled that museums haven’t quite achieved universal levels of accessibility.

At least, not entirely. Of the 30 sampled art museums, only 16.67% were able to meet or exceed standards in providing neurodiverse, physical accessibility, and educator resources.

Half of the art museums scored positively in terms of physical accessibility, demonstrating relatively better performance compared to other categories. However, there is still significant room for improvement, as 30% of art museums scored negatively.

These overall negative scores could be attributed to a variety of factors, ranging from an inadequate physical location to insufficient web accessibility features, which can impact those with neurodivergency, physical disability, and educators. An example of website inaccessibility can be found with the Metropolitan Museum of Design Detroit, which features a disjointed design. There is a lack of intuition in terms of website navigation. Typically, museum websites feature a dedicated "Education" page, appropriately titled with variations such as "Education," "Teaching," or similar terms.

The South Bend Museum of Art (see figure 21) website makes it easy to discern where one could find information regarding their educational programming. In the case of the Metropolitan Museum of Design Detroit, it is much more difficult. Educational information is located under the header “vibe”, which does not indicate education but rather an ethos or feeling.

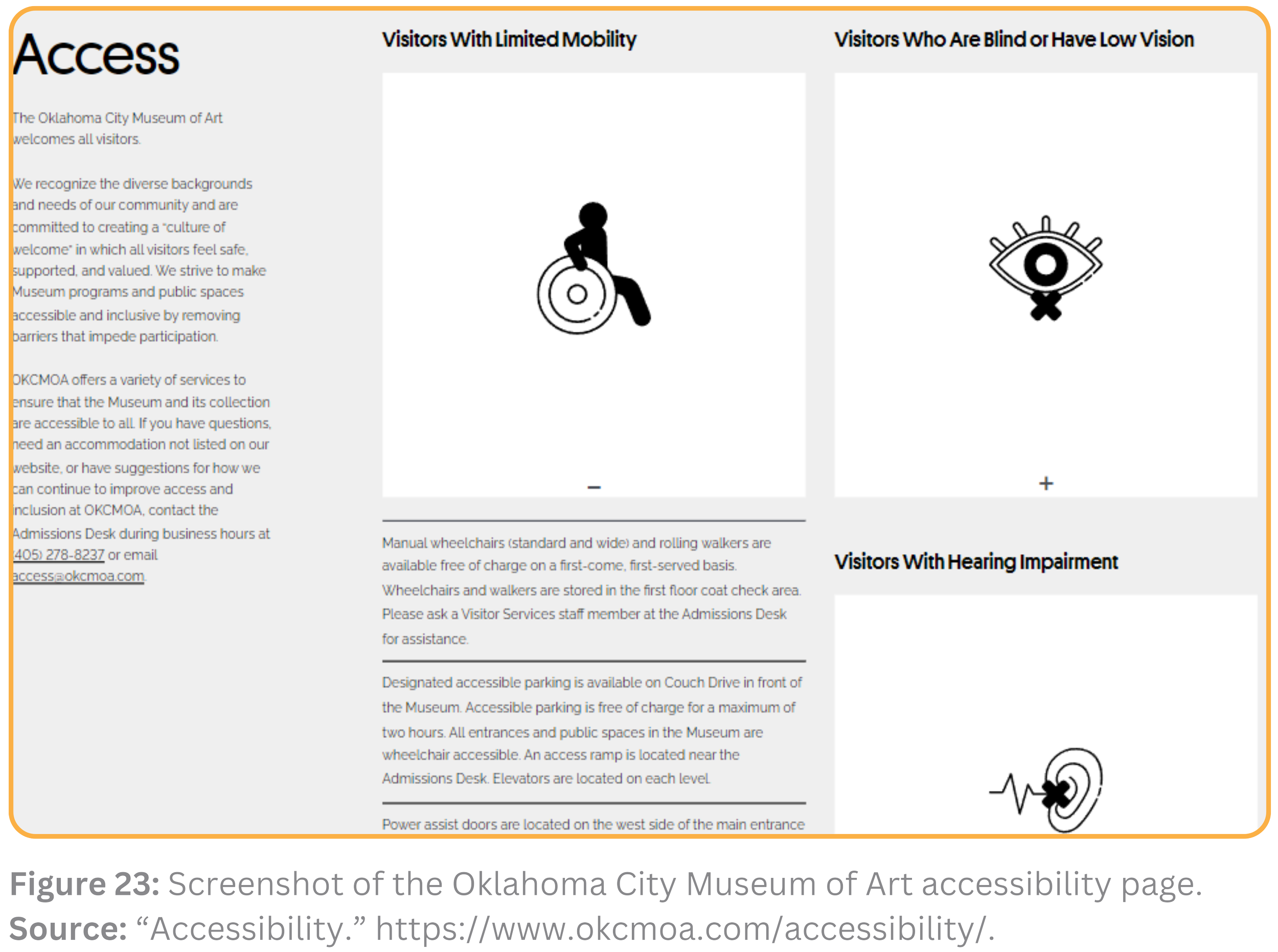

Among the most web accessible, and highest scoring museums, was the Oklahoma City Museum of Art (OKCMOA). The accessibility page includes clear subheadings, iconography, and drop downs to aid in providing the information a visitor or educator might need to know prior to visiting.

In addition to being easy to navigate, there is a wide range of resources available for neurodivergent individuals to plan their trip. In addition to noise-canceling headphones, wiggle seats, and fidgets, there are different social narratives available for all potential aspects of an art museum visit (even one for museum manners). OKCMOA also provides tailored access tours, which “...can include verbal description, sensory components, or simply provide a friendly and welcoming educator to accompany your group for one hour in the galleries.” For educators, OKCMOA offers free virtual field trips to students K-12 and in college, which focus on student-centered and inquiry-driven exploration of current exhibits.

Of course, continuous effort and investment are needed for more museums to reach this level of accessibility. Several factors can impact an art museum's ability to provide such comprehensive resources, including its location, employee count, and budget.

REGARDING LOCATION

Arts museums located in urban areas were shown to have the highest passing rates (52%), while suburban art museums have a much lower pass rate (12.50%).

However, suburban art museums have the highest borderline rate (50%), which indicates that many have the potential to improve and enhance their offerings to better meet accessibility standards. Rural art museums may appear to struggle the most with providing accessibility measures and resources to educators, with no art museums passing and a high failing rate, but there is one singular outlier representing rural art museums amongst the sample data, so this should be taken with a grain of salt.

REGARDING EMPLOYEE AND EDUCATIONAL STAFF COUNT

Many art museums within the sample set have small (1-20) or medium (21-100) employee counts, with a smaller portion having large (100+) employee counts. The qualifiers for employee counts (Small: 1-20, Medium: 21-100, Large: 100+) were specifically based on the employee counts collected via LinkedIn estimations or as reported by the art museums themselves.

The data indicates that larger art museums, with their higher passing rate of 80% and no failing scores, may be better equipped to provide neurodiverse accessibility, physical accessibility, and educator resources. A larger staff count and overall larger capacity might significantly contribute to an art museum's ability to research, implement, and properly provide accessible options for neurodiverse visitors. In contrast, smaller art museums face more challenges, likely due to capacity issues, as evidenced by their high failing rate of 46% and low passing rate of 8%. Medium-sized art museums perform relatively well, but there is still room for improvement, indicating that increased staff and resources could further enhance their accessibility offerings.

Delving further into education-related staff members, the qualifiers for educational staff counts (None Listed, Small: 1-20, Moderate to Large: 21-100) were specifically based on the data gathered on art museums' staff who hold education-related roles or have education in their job titles.

Museum educators, as defined by the American Alliance of Museums, "...seek to promote the process of individual and group discovery...[and to]... serve as audience advocates..." With that in mind, the data reveals that art museums without listed education staff can face significant challenges when it comes to providing accessibility, as indicated by their high failing rates (67%) and the absence of passing scores.

Though art museums with smaller education-related staff have mixed performance, they still outperform those without. This suggests a critical need for dedicated education staff to improve accessibility and resource provision. Individuals with backgrounds in education can offer the necessary support to help these museums enhance their offerings and better serve their audiences.

REGARDING BUDGET SIZE

Initially, the assumption was that art museums with larger budgets would have the highest passing rates, given their ability to invest in training, educational staff, and necessary accommodations to enhance the museum space. It was found that the financial status of art museums can play a significant role in their ability to meet accessibility standards, but it is, evidently, not the sole determinant of success.

Art museums with a medium-sized budget are struggling the most, with no passing or borderline scores and a 100% failing rate. Large art museums perform relatively well, with a 60% passing rate. However, a notable portion are borderline (30%) and failing (60%), indicating that even well-funded institutions can face challenges in meeting accessibility standards.

Why could this be the case? — One of the art museums that indicated having a large FY22 budget ($5,625,315.00), The Nevada Museum of Art remains on the borderline. This museum received a borderline score primarily due to its focus on physical disability resources while neglecting to provide neurodiverse accessibility options or easily accessible information regarding tours for neurodivergent students. According to the 2022 Annual Report, the Nevada Museum of Art began its multi-year, $60 million expansion project, which is anticipated to reach completion in 2025. This project represents a significant investment, but it remains to be seen whether the expansion will include enhancements to the museums’ current accessibility offerings.

Ultimately, the survey reveals that while some progress has been made, many art museums still fall short in providing comprehensive accessibility offerings, particularly for neurodiverse visitors. To better serve all audiences, museums should focus on inclusivity by investing in resources that address visitor needs (see figure 8), expanding education staff, and improving web accessibility and design.

CONCLUSION: MUSEUMS HAVE TO DO BETTER

Art museums have yet to address the unique needs of neurodivergent individuals across the board. Unfortunately, most art museums fail to provide the necessary support. Art museums have important roles in maintaining and addressing the needs of their audience, both in inviting art consumers just to walk through the door as well as making them feel welcome before, during, and after their visit.

Art museums don’t have to reinvent the wheel to begin slow, steady implementation of neurodiverse resources. That being said, they do need to take action and responsibility. A few of the art museums researched issued disclaimers on their websites, which explained their ongoing efforts towards providing better options to visitors.

By acknowledging that the process can be started gradually with small changes implemented here and there, art museums can make meaningful progress and become a space for neurodivergent people to fully engage.

-

“(1) The Language of Neurodiversity: Terms and Definitions in the Age of Inclusivity | LinkedIn.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/language-neurodiversity-terms-definitions-age-susan/.

“Accessibility - Cameron Art Museum.” https://cameronartmuseum.org/accessibility/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Museum Accessibility: An Art and a Science,” October 21, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/2022/10/21/museum-accessibility-an-art-and-a-science/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Neurodivergent Needs: A Q&A with ADDitude Magazine,” February 16, 2024. https://www.aam-us.org/2024/02/16/neurodivergent-needs-a-qa-with-additude-magazine/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Tips for Creating Accessible Museums: Universal Design and Universal Design for Learning,” November 27, 2023. https://www.aam-us.org/2023/11/27/tips-for-creating-accessible-museums-universal-design-and-universal-design-for-learning/.

“Art Museum Attendance | American Academy of Arts and Sciences.” https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/public-life/art-museum-attendance.

Ashford, Melanie. “Digital Accessibility For Physical Disabilities.” https://www.accessibility.com/blog/digital-accessibility-for-physical-disabilities.

“Ask an Autistic #13 - What Are Special Interests? - YouTube.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytWwFr5_pbY.

Castillo, Ruth Igielnik, Elizabeth Grieco and Alexandra. “Evaluating What Makes a U.S. Community Urban, Suburban or Rural.” Pew Research Center (blog), November 22, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/decoded/2019/11/evaluating-what-makes-a-us-community-urban-suburban-or-rural/.

CCC-A, Kristie Brown Lofland, M. S. “Writing and Using Social Narratives: Articles: Indiana Resource Center for Autism: Indiana University Bloomington.” Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/writing-and-using-social-narratives.html.

CDC. “Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), February 22, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html.

“Census Reporter: Making Census Data Easy to Use.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://censusreporter.org/.

Cleveland Clinic. “Neurodivergent: What It Is, Symptoms & Types.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent.

Creative Differences: A Handbook for Embracing Neurodiversity in the Creative Industries. Universal Music, 2020.

“Definition of DISJOINTED,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disjointed.

“Definition of TECHNOLOGY,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technology.

“Definition of VIBE,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vibe.

Deloitte Insights. “Creating Support for Neurodiversity in the Workplace.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/neurodiversity-in-the-workplace.html.

“Disability Language Style Guide | National Center on Disability and Journalism.” Accessed June 22, 2024. https://ncdj.org/style-guide/.

“Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion (DEAI), & Anti-Racism – American Alliance of Museums.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.aam-us.org/topic/diversity-equity-accessibility-inclusion-anti-racism/.

Doyle, Nancy. “Neurodiversity at Work: A Biopsychosocial Model and the Impact on Working Adults.” British Medical Bulletin 135, no. 1 (September 30, 2020): 108–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa021.

Editors, ADDitude. “ADHD Goes to the Museum.” ADDitude (blog), August 20, 2023. https://www.additudemag.com/overstimulated-understimulated-museum-accessibility-adhd/.

Felton, Amber. “What Is Hyposensitivity?” WebMD. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.webmd.com/brain/autism/what-is-hyposensitivity.

“Find a Museum.” https://ww2.aam-us.org/about-museums/find-a-museum.

Forbes Health. “What Does It Mean To Be Neurodivergent?,” October 4, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/what-is-neurodivergent/.

Gold, C., T. Wigram, and C. Elefant. “Music Therapy for Autistic Spectrum Disorder.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 2 (April 19, 2006): CD004381. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub2.

“Home | Oklahoma City Museum of Art | OKCMOA.” https://www.okcmoa.com/.

“How Field Trips Boost Students Lifelong Success.” https://www.neamb.com/work-life/how-field-trips-boost-students-lifelong-success.

Insights of a Neurodivergent Clinician. “Sensory Overload and Emotions.” https://neurodivergentinsights.com/blog/sensory-overload-and-emotions.

Learning Differences for Young Children, Teens and Young Adults, March 31, 2021. https://www.chconline.org/resourcelibrary/adhd-symptoms-unmasked-by-the-pandemic-diagnoses-spike-among-adults-children/.

Lord, Barry. The Manual of Museum Learning. Rowman Altamira, 2007.

“Making Content Usable for People with Cognitive and Learning Disabilities.” https://www.w3.org/TR/coga-usable/.

Marco, Elysa Jill, Leighton Barett, Nicholas Hinkley, Susanna Shan Hill, and Srikantan Subramanian Nagarajan. “Sensory Processing in Autism: A Review of Neurophysiologic Findings.” Pediatric Research 69, no. 5 Pt 2 (May 2011): 48R-54R. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54.

MEd, Nicole Baumer, MD, and Julia Frueh MD. “What Is Neurodiversity?” Harvard Health, November 23, 2021. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-neurodiversity-202111232645.

MMODD. “Metropolitan Museum of Design Detroit | We Are a Design Museum in Detroit | 905 Henry Street, Detroit, MI, USA.” Accessed August 15, 2024. https://www.mm-o-dd.org.

Museum of Pop Culture. “Accessibility.” https://www.mopop.org/visit/accessibility/.

Museum, The Walters Art. “Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion Goals,” n.d.

“Neurodiversity in the Workplace.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://askearn.org/page/neurodiversity-in-the-workplace.

“Neurodiversity, Neurodivergent, Neurodiverse, Neurotypical – Editorial Style Guide.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://editorial-styleguide.umark.wisc.edu/term/neurodiversity-neurodivergent-neurodiverse-neurotypical/.

Oklahoma City Museum of Art | OKCMOA. “Accessibility.” https://www.okcmoa.com/accessibility/.

Rondeau, James. “An Update on Our Racial Justice and Equity Work,” June 3, 2021. https://www.artic.edu/articles/928/an-update-on-our-racial-justice-and-equity-work.

“Sensory Differences - a Guide for All Audiences.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/sensory-differences/sensory-differences/all-audiences.

SFMOMA. “March 2021 Update: Institutional Commitments.” Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.sfmoma.org/dei-actions/dei-update-march/.

“South Bend Museum Of Art – SEE, BELONG, MAKE.” https://southbendart.org/.

Staff, Kappan. “The Benefits of Multiple Arts-Based Field Trips.” Kappan Online, April 26, 2021. https://kappanonline.org/benefits-multiple-arts-based-field-trips-florick-greene/.

“Stimming: What Is It and Does It Matter? | CHOP Research Institute.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.research.chop.edu/car-autism-roadmap/stimming-what-is-it-and-does-it-matter.

Teach Online. “Designing for Neurodiversity,” April 11, 2023. https://teachonline.asu.edu/2023/04/designing-for-neurodiversity/.

Team, ADDA Editorial. “ADHD & Hyperfixation: The Phenomenon of Extreme Focus.” ADDA - Attention Deficit Disorder Association (blog), March 20, 2023. https://add.org/adhd-hyperfixation/.

“The Push and Pull for Accessibility,” October 25, 2023. https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2023/push-and-pull-accessibility.

“The Value of Art Therapy for Those on the Autism Spectrum,” March 31, 2017. https://www.3blmedia.com/news/value-art-therapy-those-autism-spectrum.

Tuckman, Ari, Psy.D., and MBA. “Why Deadlines Pounce and Long-Term Plans Never Happen.” ADDitude, June 27, 2017. https://www.additudemag.com/how-to-plan-ahead-when-you-have-adhd-understand-time/.

Understood, Autism. “Information Processing Differences.” Autism Understood, June 5, 2023. https://autismunderstood.co.uk/autistic-differences/information-processing-differences/.

“Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications | DO-IT.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.washington.edu/doit/universal-design-process-principles-and-applications.

“Using Universal Design for Empowering Neurodiversity in the Classroom,” February 24, 2020. https://sites.tufts.edu/teaching/2020/02/24/using-universal-design-for-empowering-neurodiversity-in-the-classroom/.

Verywell Mind. “Overstimulation in ADHD.” https://www.verywellmind.com/adhd-symptom-spotlight-overstimulation-5323859.

Wakeman, Caressa. “June 23, 2024 | Neurodiversity in Engineering,” June 28, 2022. https://neurodiversity.engineering.uconn.edu/2022/06/.

Watson, Angela R. “Arts Smarts or Random Visits: Arts Field Trips in the American Education Policy Context,” n.d.

“WebAIM: Evaluating Cognitive Web Accessibility.” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://webaim.org/articles/evaluatingcognitive/.

“What Do We Know About Noise Sensitivity in Autism?” Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.kennedykrieger.org/stories/interactive-autism-network-ian/noise-sensitivity-autism.

“What Is Physical Accessibility? | National Disability Navigator Resource Collaborative.” https://nationaldisabilitynavigator.org/ndnrc-materials/disability-guide/what-is-physical-accessibility/.

World Economic Forum. “Explainer: What Is Neurodivergence? Here’s What You Need to Know,” October 10, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/explainer-neurodivergence-mental-health/.

WYSE Travel Confederation. “Travel Improves Educational Attainment & Future Success,” October 24, 2013. https://www.wysetc.org/2013/10/travel-improves-educational-attainment-future-success/.

Yum, Lori Deuchar. “ADHD Symptoms Unmasked by the Pandemic: Diagnoses Spike Among Adults, Children.” CHC Resource Library, March 31, 2021. https://www.chconline.org/resourcelibrary/adhd-symptoms-unmasked-by-the-pandemic-diagnoses-spike-among-adults-children/.