Written by Carol Niedringhaus

Introduction

“Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope.” The iconic opening scenes from the original Star Wars film, A New Hope, epitomize what we think of when we consider the word “hologram.” In the film, Princess Leia Organa records a message that is stored in R2-D2’s memory and is later projected as a life-like, three-dimensional image to Luke Skywalker and an aged Obi-Wan, making it seem as though she were in the room with them. The surprise and awe displayed by Luke when viewing this futuristic message is mimicked by many audience members even to this day. In the minds of science fiction fans everywhere, the hologram is a concept that evokes feelings of wonder at the possibilities for technological advances.

Obi-Wan Kenobi and Luke Skywalker viewing Princess Leia’s hologram in the first Star Wars film. Source: Smithsonian Magazine

But what is a hologram? According to Sean Johnston an educator at the University of Glasgow, the word “hologram” has morphed over the years from its original intended purpose of describing a scientific process, to a word associated with particular cultural connotations. First introduced to the public consciousness in the 1960s, the word itself has become a cultural phenomenon eliciting connections with “magic, modernity, and optimism” rather than a realistic output that can be viewed or used by the general public. This makes breaking down what holograms are challenging since the word itself is less of an object and more of a concept in the collective consciousness.

In order to understand holograms and the art of holography, one must look at it from a scientific perspective as well as from an arts and cultural perspective. This article will attempt to describe the scientific origins of holograms, contextualize holography’s use in the visual arts, and analyze their current and potential future place within the popular music industry. These perspectives will serve as a demonstration as to how holograms have disrupted the arts in the past and the implications of current holographic disruptions within the industry.

Holograms as a Scientific Concept

A hologram is defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as, “a three-dimensional image reproduced from a pattern of interference produced by a split coherent beam of radiation.” While this is a practical definition, it is confusing and does not fit well with our science fiction interpretation of holograms. Holography itself is a complex scientific process with a long history of development and use dating back almost 75 years and continuing into the present era.

Scientist Dennis Gabor developed the “Theory of Holography” in 1947 while conducting research on improving the image resolution of electron microscopes. He would go on to win a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1971 for “his invention and development of the holographic method.” This process is referred to as “electron holography” and is still used in electron microscopy today. However, what we envision when talking about holograms is “optical holography,” which is the process of creating three-dimensional objects with light. Because of the inability to create fully “coherent” or monochrome light sources, development of these optical holograms did not begin until the 1960s. With the invention of lasers, a much more powerful light source than previously available, by Russian scientists in 1960, other scientists were able to continue experimenting with the concept, eventually creating the first 3D holographic image in 1962. From there, holography was utilized as a new visual medium that was continually improved upon by scientists through the 1970s until it eventually lost its allure and became less popular over the following decades.

The process of creating a hologram is complicated. It is a difficult feat to create a 2-dimensional image that appears three-dimensional and seems to move as the viewer moves; an optical illusion called the “parallax effect.” Transmission holograms, first produced by scientists Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks in 1962, are the most common type of hologram and are produced by “…shining laser light through [the recording medium] and looking at the reconstructed image from the side of the hologram opposite the [light] source.”

The process of creating a transmission hologram. Source: researchgate.net

This helpful video from Physics Girl provides an in-depth, understandable look at the physics involved in creating Transmission hologram images. For those without time to watch, here is a quick summarization of the main points regarding how a hologram is created. First, a single laser beam is utilized and passed through a lens where it is split into two separate beams. Then, each beam is sent through a “beam spreader” to make them spread out. One of the beams, called the “object beam” bounces off the object being imaged and is then projected onto the holographic film. The second beam, called the “reference beam,” is projected directly onto the holographic film without bouncing off of another image. When the beams meet on the holographic film, they create an interference pattern that is specifically coded through this process, to produce a 3D holographic image of the object. Although this represents a simplistic version of the physical phenomena happening, it can give non-physicists a good idea of how the process of creating a hologram actually works.

While the process of creating a hologram is universal, there are distinctions within holography regarding how light it utilized to produce the image. A second type of hologram that was developed after the Transmission hologram is called a “rainbow transmission” hologram that allows illumination through white light rather than utilizing lasers. More recently, researchers at the University of Rochester debuted a new type of hologram display system called the Illumyn 3-D display that comes closest to producing the futuristic holograms seen in science fiction.

Illumyn 3-D display. Laser light must be projected through the glass sphere in order to create the holographic image. Source: KPBS News

It uses lasers to project a 3D image in mid-air without the need of a projection screen or holographic film. However, it does require the use of a glass sphere containing Cesium vapor (an elemental metal), so it still is not possible to create 3D projections in mid-air without the use of a secondary source to project the light in the correct manner. These examples are by no means the only types of holograms that can be created, but it provides some context for the breadth of holography as a science and how researchers are actively working to improve upon the existing technology.

Holography and the Arts

With the discovery of holograms as a scientific process, their popularity grew among artists in the 1970s until their novelty gradually waned in the 1980s. Among other non-microscopy uses, holography was publicized by the engineering industry “…as ‘lensless 3D photography.” The prediction was that holography would eventually replace traditional photography as well as traditional television and movies as the entertainment media of choice. This prediction was clearly incorrect. However, artists still used holograms in various exhibitions and there are excellent examples of holographic imaging being used in the visual arts.

In 1968, UK artist Margaret Benyon was able to obtain the necessary equipment to experiment with holographic art through an arts fellowship at Nottingham University. She is credited with laying the groundwork for “…critical discussion around the process [of holography] and its use by artists.” Her doctoral thesis examined the “Art of Holography” and here pioneering work earned her the distinction of being the “mother” of British creative holography. Her work is referenced frequently in academic writings regarding holographic art.

The Tigirl by Margaret Benyon. Source: The Conversation

Pushing up the Daisies by Margaret Benyon. Source: Gallery 286 London

With this rise in the availability of equipment and overall popularity, museums specializing in displaying holographic artworks began appearing in the 1970s. However, as an art form, holography never was truly considered an artistic medium. Distinctions began emerging between artists whose primary medium was holography and those artists who merely experimented with holography, but who still focused the bulk of their practice in traditional mediums. Even though holography showed promise as an emerging art form, it never reached the level of acceptance that allowed museums and galleries to display those artists’ works unless the artists was already a known contributor to their collections.

Part of this lack of inclusion in traditional arts spaces may have to do with the practical considerations revolving around how holographic art must be displayed. Melissa Crenshaw writes in her article entitled “The Dynamic Display of Art Holography” that the way holography exhibitions are displayed can either “…enhance or diminish the impact of the images…” based on lighting and other exhibition factors. Additional writing from a 1996 article entitled “Display and applied holography in museum practice” thoroughly lays out the scientific criteria necessary for successfully presenting a holographic display. The writing in this particular article is extremely dense and relies on the mathematics and physics required to achieve a successful hologram. It is no wonder museums may be hesitant to display these artworks when the implementation of such works is, by nature, detailed and complex. Thus, places such as the Museum of Holography specialize in making sure holographic works of art are provided the opportunity to be displayed in an authentic setting, while also engaging audiences through education about holography as a science and as an art form.

Holographic exhibitions have been, and will continue to be, an important part of artistic work produced around the world. Exhibitions like those that took place in 2017 in London, New York, and New Mexico, as well as a 2018 academic symposium dedicated to discussion about holographic art and technology, speaks to its lasting place in the artistic sphere.

Popular Music and Modern “Holograms”

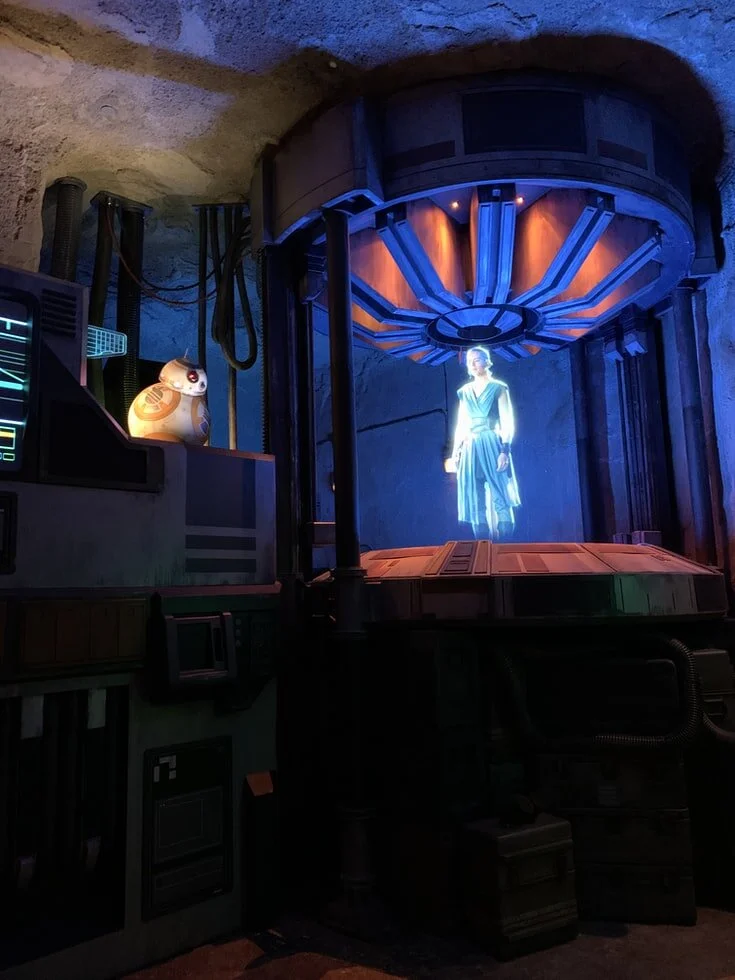

In addition to holography making its way into the visual arts world, holograms have recently been taking the music industry by storm. But the holographic techniques utilized for performance art look exceptionally different from those utilized in the visual arts. They differ so drastically that they are not, technically speaking, holograms at all. In most cases, the “holograms” being displayed are no more than an optical illusion. The illusion is known as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ and has been in use since the 1860s. It is produced by using a reflection of an unseen object to generate a ghostly image that appears to float across the stage. However, unlike a real hologram, the image is “…a 2D trick…” most well-known for being used in the Disney attraction “The Haunted Mansion” where ghostly figures appear to dance around the haunted ballroom. Although the holograms produced for touring performances are created by much more evolved technology, the basic principle is more closely related to the idea behind ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ than it is to a complex optical hologram. Yet, the allure of these “holograms” remains strong among popular music lovers, regardless of the scientific and semantic issues.

The “hologram” craze started in 2012 at the annual Coachella festival. Unbeknownst to the audience, a digitally recreated 3D image of slain rapper Tupac Shakur walked onstage and performed a set of songs with the popular artist Snoop Dogg.

Snoop Dogg and a hologram of deceased rap icon Tupac Shakur perform at the 2012 Coachella festival. Source: Artnet

This event served as a catalyst for the music industry and more and more iconic, deceased stars have seen a rebirth in their careers from beyond the grave. Stars such as Michael Jackson, Buddy Holly, Roy Orbison, Frank Zappa, Whitney Houston, and opera singer Marie Callas represent a few of the popular artists brought back to life for international tours and performances after their death. Watching videos of the performances of these dead artists is surreal. But people are gravitating toward these live performances as an in-demand form of performance art, which has seen recent popularity throughout the world even outside of the music industry.

In addition to the rising desire for performance art rather than traditional static art, there is also the issue of the impact of artistic legacies. Even after a performer passes, it is not uncommon to see their work become more popular, at least for a while immediately following their death, thus providing the industry with renewed economic support. According to Pollstar, “Roughly half of the top 20 top-grossing North American touring acts of 2019 were led by artists who were at least 60 years old.” This trend indicates that hologram technology could help to sustain a music industry that is currently built on an aging demographic that could collapse with the passing of any of the most beloved stars.

Beyond the implications for the music industry and its sustainability, the recent popularity of hologram concerts has opened up a new business opportunity. Base Hologram has become the leading hologram production company, securing the rights to acts including Maria Callas, Buddy Holly, and Whitney Houston, whose hologram was set to go on an international tour in 2020. The company credits its success to its advancement of the technology originally used to create the Tupac CGI image in 2012 to something that requires fewer practical limitations and better visual quality. Base Hologram states on their website that the company “….harnesses the magic of holographic live and out-of-home entertainment to create concerts, theatricals and spectacles to entertain all types of audiences…,” in order to create performances all over the world that seamlessly integrate real and holographic elements. The company uses a different kind of screen for their projections which allows for easier set up and tear down and allows the image to be projected directly onto the screen rather than using the Pepper’s Ghost technique. Although impressive, this technology does not have the ability to create a character in 3D that can do more than walk back and forth across the stage. The technology, as discussed earlier in this paper, does not yet exist at that level to create free-standing, 3D holographic projections.

With increased demand has come increased scrutiny. Ethical questions about “reanimating” dead performers have been abundant since this technology started being used. One journalist, Simon Reynolds, argued that these hologram performances could be considered “ghost slavery,” as the artist had no say in whether their likeness was used. Others argue that recreating the images of these singers negates the inherent beauty of the music they left behind by “…grafting a false image…” to their iconic images. Some have even gone so far as to call it “tacky and exploitative” as well as just plain dumb. Still, others, including various highly visible celebrities, are fans of the emerging trend of hologram concerts. It is a multi-faceted issue that currently does not have a clear answer.

Conclusion

Whether someone is a fan of science fiction or not, it can be agreed that holograms have had a distinct impact on the arts. Although they were not initially intended for anything other than scientific use, holograms made their way into the public’s imagination and conjured up ideas of the future of technological advances. While holographic art has not maintained the popularity in visual arts that it enjoyed in the 1970s and 80s, audiences are increasingly interested in seeing holograms, of a sort, through popular music performances around the world. It remains to be seen whether this development in the music industry leads to lasting change or whether the ethical debates and divided opinions will render it an odd part of artistic history. In any case, holograms have disrupted, and continue to disrupt, the arts. As we look towards the future, we must acknowledge the significance of this technology and prepare for a new, mixed-reality world where tactile artistic mediums intertwine with holograms. And perhaps one day we will be able to channel our inner Princess Leia and send a hologram message to a galaxy far, far away.

+ Resources

Crenshaw, M. Melissa. “The Dynamic Display of Art Holography.” Arts 8, no. 3 (September 2019): 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030122.

“Definition of HOLOGRAM.” Accessed April 7, 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hologram.

Dinsmore, Sydney. “Reviewing the Inclusion of Artists’ Holograms in the Permanent Collections of Fine Art Museums.” Arts 8, no. 4 (December 2019): 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040147.

“Famous German Circus Replaces Live Animals with Cruelty-Free Holograms.” Accessed March 30, 2021. http://cladglobal.com/news?codeid=342231.

“Five Surprising Ways Holograms Are Revolutionising the World.” The Conversation. Accessed March 30, 2021. http://theconversation.com/five-surprising-ways-holograms-are-revolutionising-the-world-77886.

Harman, Mary. “Holographic Reconstruction of Objects in a Mixed-Reality, Post-Truth Era: A Personal Essay.” Arts 8, no. 3 (September 2019): 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030102.

“History of the Holography.” Accessed April 7, 2021. http://www.holography.ru/histeng.htm.

TheFreeDictionary.com. “Holographic Art.” Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Holographic+art.

“Holography - Wikipedia.” Accessed April 7, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holography.

Base Hologram. “Home Page.” Accessed March 30, 2021. https://basehologram.com/.

Ifeanyi, K. C., K. C. Ifeanyi, and K. C. Ifeanyi. “The Hologram Concert Revolution Is Here, Whether You like It or Not: Meet the Company Touring Whitney Houston and Buddy Holly.” Fast Company, June 19, 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90365452/hologram-concert-revolution-like-it-or-not-meet-company-touring-whitney-houston-buddy-holly.

John, Pearl. “The Silent Researcher Critique: A New Method for Obtaining a Critical Response to a Holographic Artwork.” Arts 8, no. 3 (September 2019): 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030117.

Johnston, Sean. “Holograms: The Story of a Word and Its Cultural Uses.” Leonardo 50 (July 11, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_01329.

Markov, V. B. “Display and Applied Holography in Museum Practice.” Optics & Laser Technology, Holography in the CIS, 28, no. 4 (June 1, 1996): 319–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-3992(95)00104-2.

Meier, Allison C. “The Rise and Fall of Hologram Art.” JSTOR Daily, May 7, 2019. https://daily.jstor.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-hologram-art/.

Ottewill, Jim. “How Hologram Technology Is Changing the Future of the Music Industry,” MusicTech. May 9, 2019. https://www.musictech.net/features/trends/hologram-technology-future-of-music-industry/.

“Patrick Boyd | Gallery 286 London.” Accessed April 8, 2021. http://www.gallery286.com/patrick-boyd-2017/.

Pepper, Andrew. “Fence-Sitting and an Opportunity to Unsettle the Settled: Placing Critical Pressure on Creative Holography.” Arts 9, no. 1 (March 2020): 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010034.

Physics Girl. How 3D Holograms Work, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ics3RVSn9w&t=238s. ppandp. “Aura Kinetica.” Currents New Media. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://currentsnewmedia.org/work/aura-kinetica/.

Reed, Ryan, and Ryan Reed. “Whitney Houston Hologram Tour Plots First 2020 Dates.” Rolling Stone (blog), September 17, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/whitney-houston-hologram-tour-2020-dates-image-885666/.

Schneider, Tim, January 13, and 2020. “The Gray Market: What the Craze for Holograms of Dead Pop Stars Could Mean for the Market for Performance Art (and Other Insights).” Artnet News, January 13, 2020. https://news.artnet.com/opinion/pop-star-holograms-performance-art-1750800.

KPBS Public Media. “Why Don’t We Have Princess Leia Holograms Yet?” Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/aug/26/why-dont-we-have-princess-leia-holograms-yet/.

Smithsonian Magazine. “Why Holograms Will Probably Never Be as Cool as They Were in ‘Star Wars.’” Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/holograms-are-no-longer-future-180961597/.