Before the Birmingham Museums Trust in the UK moved to share some of their digitized collections as open access, they made about £12,000 from image licensing fees. After the organization embraced open access policies for these works, they lost half of those funds. However, their marketing department estimates that since they have received £100,000 of press coverage. While those numbers are impressive themselves, Linda Spurdle, Digital Development Manager, emphasizes that they do not nearly cover the other perspective: the impact on people using the collections.

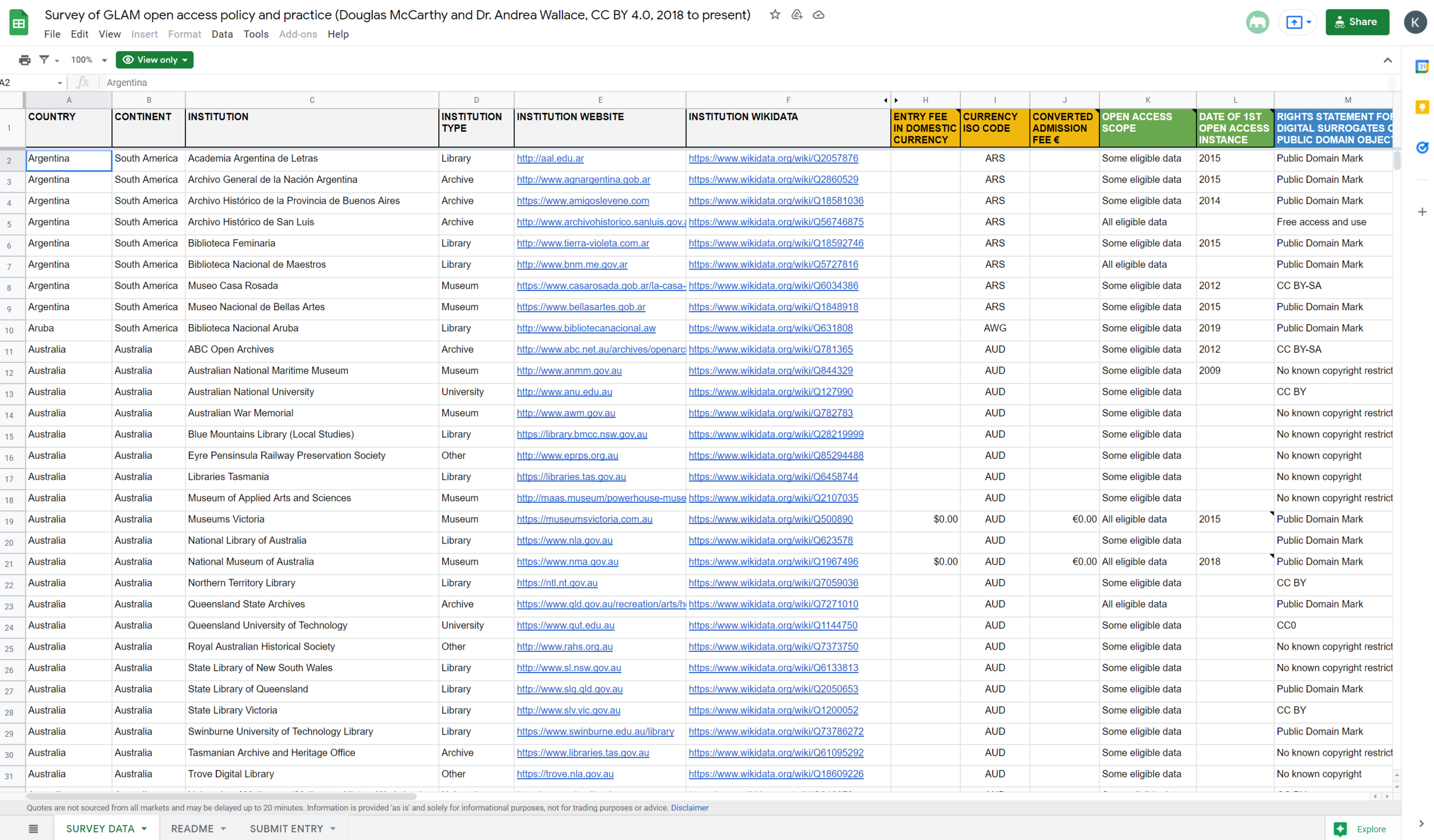

According to the Western Museum Association, Open Access refers to efforts made by museums to provide high-resolution downloadable images free of charge to maximize the ability of the user to interact with, share, and reuse the images. More information on Open Access can be found in the article: What is Open Access and Why Does it Matter in the Museum Space? In 2018, Douglas McCarthy, Collections Engagement Manager at Europeana, and Dr. Andrea Wallace, Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Exeter, set out to see how many cultural heritage institutions make their digital collections available for free use, as well as how they do it. The pair created a Google Sheet survey that has listed over 1,200 international institutions, including Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums.

Figure 1: A preview image of the Open Access survey. Screenshot by Author.

Over one-third of these records name specific Museums. While Open Access encompasses numerous industries, this article focuses Open Access technology and usage in the context of Museums and Artists. It summarizes findings on the utilization and impact of Open Access initiatives into three conclusions:

1. The technology of open access is critical to its usage in collections

2. Open access collections provide more commercial opportunities for artists

3. Open access collections create deeper conversations on the role of museums

Part 1: The Technology of Open Access is Critical to its Usage in Collections

Metadata & Its Importance to Open Access

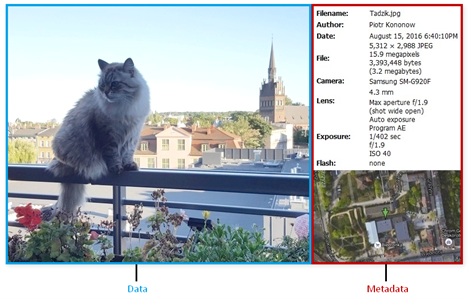

Metadata, simply put, is ‘data about data’. Metadata is the information that is stored within a file or document that would not be obviously evident in looking at the file or document. In fact, metadata is incredibly frequent in daily life through pictures taken, music listened to, blog posts read, etc. Figure 1 shows metadata in the context of a snapped photo.

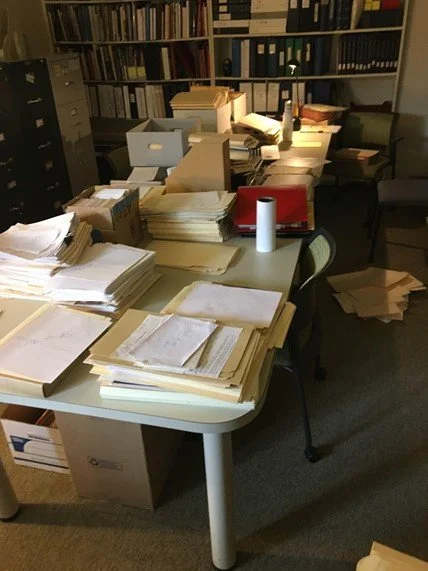

Figure 2: The difference between data and metadata shown through an example of a photo of a cat. Source: Dataedo.

In the context of this blog post, it is the title, author name, published time, category, and any other relevant tags on the post. In the context of Museum objects, it is the title, artist, date, medium, dimensions, provenance, etc. The University of Notre Dame’s MARBLE platform, standing for Museums, Archives, Rare Books, & Libraries Exploration, encourages comparative research for both Notre Dames’ Hesburgh Libraries and Snite Museum of Art and allows students, alumnus, and staff in the field to provide resources and posts about their processes. Alumnus Liam Maher detailed his experience at the Snite Museum of Art, cleaning up metadata to allow the organization to digitize. Maher concluded that the process of cleaning up and digitizing metadata would allow visitors to view collections more in-depth, immerse themselves in exhibitions from the past, and better understand the institution’s history and its role in the global art scene. Maher also emphasized, “Every digitized collection requires months of planning and development, usable and flexible metadata, and meticulous editing and updating information.” Figure 3 shows a look at the metadata Maher organized and digitized.

Figure 3: Exhibitions files: important metadata, from the Snite Museum of Art. Source: Liam Maher on MARBLE.

Similarly, on the MARBLE platform, Hanna Bertoldi details how important standard language is to the program, stating: “Museum metadata has the potential to bridge gaps between cultural heritage institutions and provide access beyond virtual and physical barriers. This unbounded potential can only be leveraged by using accurate and standardized metadata.” Regarding the term ‘standardized metadata,’ The Getty Research Institute developed standard controlled vocabularies for cataloging art, architecture, decorative arts, visual surrogates, art conservation, and bibliographic materials to foster interconnectedness among data and information. For example, if one museum uses ‘Claude Monet’ and another utilizes ‘Oscar-Claude Monet,’ the museum world would be hindered in collaborating, sharing, and improving information on his works and career.

While the Getty Vocabulary allows a standardized system for mapping data, this vocabulary only began to be developed in the 1980s. Even Getty acknowledges its limitations, stating, “The Getty Vocabularies strive to be ever more multilingual, multicultural, and inclusive.” How many more museums like the Snite Museum are still utilizing and relying on paper data, or haven’t even begun to make sense of standardized language? Both Maher’s story and Bertoldi’s words emphasize that while metadata is critical to the collaboration of institutions between each other in the public, the process is time consuming and requires upkeep and precision.

As more institutions adapt to standardized language and digitize their metadata, both the public and other institutions can began interacting with and exploring works on a deeper scale. Open Access specifically allows metadata on museum objects to be accessible and used by the public. For example, Figure 3 shows an Open Access image of Frederic Edwin Church’s painting, Twilight of the Wilderness, from the Cleveland Museum of Art Collections.

Figure 3: Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860. Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826-1900). Oil on canvas; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund 1965.233 Source: CMA.

The sharing of metadata in Open Access collections varies, with the Cleveland Museum of Art sharing 35 lines of metadata where available, and other Open Access museums sharing none. Thus, as more institutions expand metadata offerings, other institutions can benefit from better understanding their own collections’ objects. Additionally, those interacting with the work gain a deeper understanding of an objects past and acquisition, which in the realm of Museums, may not necessary be by ethical means. This article digs deeper into these discoveries and conversations in Part 3.

What is API and what does it mean for Open Access Collections?

API, the acronym for Application Programming Interface, connects two applications and allows them to ‘communicate’ to each other. As a software intermediary, API transfers information to and from different platforms, similar to how a waiter communicates an order to a kitchen. As an example, travel sites like Kayak or Expedia use airline’s API to communicate with airline databases and return the most recent information.

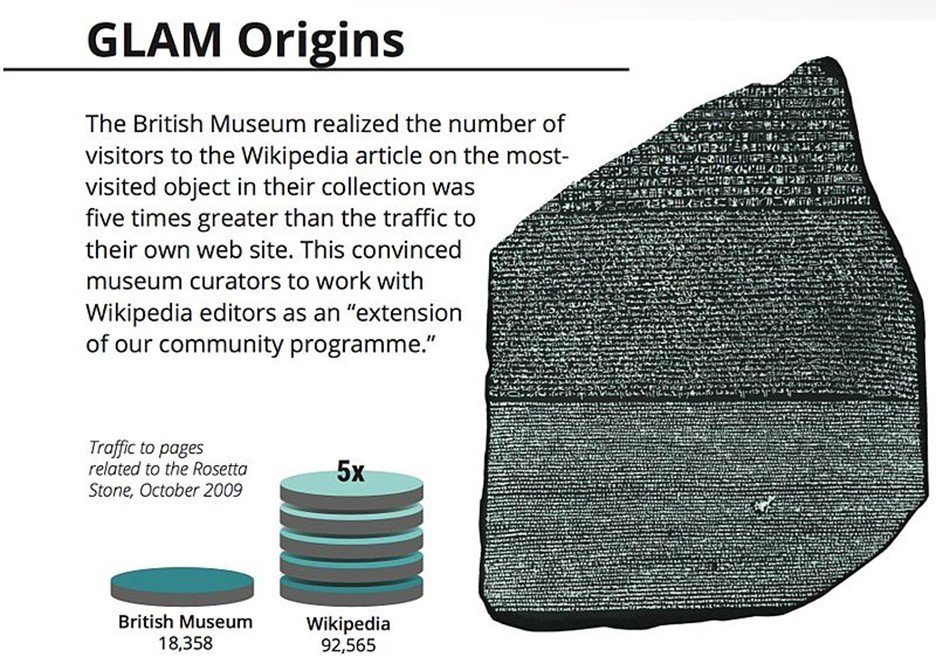

In the realm of Open Access, museums leverage API to allow developers to pull current access to their data and images. For example, Wikimedia, Internet Archive, Artstor, Artsy, and Creative Commons have incorporated the Cleveland Museum of Art’s collections into their website through the museum’s API, allowing the sites to regularly update with any new content or changes. These collaborations are critical for museums, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: How public traffic varied between Wikipedia and the British Museum regarding the Rosetta Stone. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

As such, collaborative extensions of collection with sites like Wikipedia allow for museum collections and information to be more heavily accessed and viewed by the public. Programmable Web details the top 10 Museum APIs based on website visits. These include: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, London’s Natural History Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, and others.

In the context of Open Access initiatives, available APIs allow developers to access data, giving way to more interpretations and findings within collections. For example, the Smithsonian Institution, as part of their Open Access launch, released an API in addition to a GitHub data repository. Doing such allows students, researchers, programmers, and data scientists data access and platform integration. Fifteen students from the Parsons School of Design plugged into these tools with the Smithsonian, creating various projects that answered questions about the collections. For instance, student James Troxel utilized the Smithsonian API to map various geolocation points for gems and minerals in the Natural History’s Mineral Sciences collection, called the Smithsonian Rock Ranger.

Figure 5: A glimpse of the Smithsonian Rock Ranger. Source: Smithsonian Rock Ranger.

Thus, accessible APIs allow stronger collaboration between various public facing channels, like Wikipedia, and museums to increase public awareness and engagement with collections. Open APIs allow for stronger usage of the collections, better understandings of collections, and new interpretations about collection data. As seen in the collaboration with Parsons students, the technology of Open Access gives more creative opportunities to creators and researchers.

Part 2: Open Access Collections Provide More Commercial Opportunities to Artists

While the technology of Open Access is integral to its usage, so are the policies guiding it. Creative Commons Licenses allow Open Access works to be downloaded, shared, and reused for commercial purposes. While Creative Commons licenses vary greatly in their allowance of how artists can share and reuse the works, most large institutions like the Smithsonian, CMA, Metropolitan, etc, have utilized a Creative Commons Zero license that allows images to be shared for commercial purposes without acknowledgment. This allows for creators to financially gain from their creations that incorporate works from Open Access collections. While artists can repurpose works in creations of their own, the usage of collections varies, ranging from Museums sponsoring usages and collaborations to artists applying AI and Machine Learning to the collections.

Museums sponsor collections usage

While managing API, metadata, and digital collections entail time and effort, London’s Natural History Museum shares that while it has only digitized around 6% of its collections, the investment has cost tens of millions of pounds. Therefore, it is no surprise museums have sponsored the usage of their digital collections. Upon the launch of their Open Access initiatives, the Cleveland Museum of Art partnered with artists at American Greetings to create greeting cards that used images of the artwork from the collections. Figure 5 shows an example from this collaboration.

Figure 5: A greeting card from American Greetings that incorporates artwork from the CMA. Source: Cleveland.com.

This collaboration went even further, as American Greeting artist, Jess William, created a storyboard and vision for an animation (see Figure 6) that utilized 2 other paper artists, Cheryl Cochran and Randall Slaughter, as well as animator, Jon Adler.

Figure 5: Creative Direction, 2019. Jess Williams, Cheryl Cochran, Randall Slaughter, and Jon Adler. Source: Cargo Collective.

Once again, this collaboration presented another layer, as it resulted in an entire event: “A Taste of Creative.“ It was created to celebrate art and creativity in Cleveland through DIY card bar and collage workshops.

While the collaboration with American Greetings is one example of an increase in commercial opportunities, Museums sponsoring public engagement with their Open Access collections can also be seen in larger commercial forms. One such example is the collaboration between the Cooper Hewitt Interaction Lab and the Smithsonian Institution, sponsored by Verizon 5G Labs. This collaboration, Activating Smithsonian Access, called for proposals to create new digital interactions with any of the Smithsonian’s 3 million Open Access objects. This collaboration not only was a sponsoring of the collections, but the partnership granted $10,000 to seven finalist teams for their projects to be developed to function and be used by the public. One example of the 7 projects, Art Echo, leverages the teaching of Thomas Tajo, a blind echolocation user and teacher, to reveal the acoustic attributes of various 3D objects in the collections.

Figure 6: A preview of one gallery in the ArtEcho experience. Screenshot by Author.

Collaborations, such as ArtEcho, not only show new ways artists are interpreting and utilizing collections, but increase the physical access to objects and information. Thus, with Open Access collections, artists have access to more information and data, as well as increased commercial opportunities with museum institutions.

Open Access collections in Artists’ practices

Open Access initiatives not only provide opportunities for artists and creators through sponsorships, but also provide collections that can be reused. Two specific bodies of work showcase the utilization of open collections in practice. In her body of work, Regeneration Through Technology, artist Amy Karle, leveraged 3D scans of a fossilized Triceratops skeleton to create various artworks. The works take the first 3D scan of entire dinosaur skeleton, a 66-million-year old Triceratops skeleton known as “Hatcher,” and expands onto what computer-assisted technology can mean by "looking to the future. Karle’s work, Morphologies of Resurrection, leverages scan data from the spine of the dinosaur, depicting hypothetical evolutions of species through technological regeneration.

Figure 7: One work from Morphologies of Resurrections, 2020, Amy Karle. Source: Amy Karle.

While Karle’s work utilizes Open Access collection scan data to create her own artistic works, artist Refik Anadol similarly leverages technology with Open Access collections to create works. Specifically, Anadol trained an artificial intelligence model with the public metadata of the Museum of Modern Arts’ (MoMA) collection. Anadol’s AI-based images – machine interpretations of works in the collection – use a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), a type of neural network that generates new content based on a dataset. The following image (Figure 8) highlight various works Anadol produced with the collection. The works became an exhibition, Unsupervised, at the MoMA, and were released to collectors as NFTs.

Figure 8: Unsupervised — Machine Hallucinations — MoMA Dreams — A (etc.), 2021. Refik Anadol. Source: MoMA.

Both of Karle’s and Anadols works present two different ways Open Access collections can be utilized by artists. With more collections opening to commercial reutilization, artist have increased data sets, images, and opportunities for both technological and creative advancements in their own works.

Part 3: Open Access Collections & the Role of Museums

It is important to note that museums throughout history have served the role of deciding whose voices should be heard, creating unilateral relationships with the public. In the 21st century, this role has begun to shift, with museums building bilateral relationships and attempting to be audience driven. This shift importantly, as the Smithsonian Institution emphasizes, “entails museums being inwardly focused on their collections to being outwardly focused on providing service to their audiences.” While open access allows museums to embrace that shift, the initiatives have brought both artists and museum to further evaluate this changing role.

Artists on Museums’ problems through Open Access

With more artists engaging with museum collections through Open Access, artist have leveraged the opportunity to recognize and point out key issues in the role of museums. As more museums share metadata on the history and acquisition of works, as well as open access to controversial works, artists question these histories through their own creative interpretations. As part of the Activating Smithsonian Open Access project previously mentioned, team members, Mayowa Tomori, Michael Runge, Rita Troyer, Olivia Cueva, and Olu Gbadebo, created Casting Memories to address the controversial histories of the Benin Bronzes and honors the people of Benin with a way for them to experience their art. The team utilized open access images and with 3D modeling software and recreated some of the looted Benin Bronzes (Figure 9).

Figure 9: A view of one of the 3D recreated Bronzes. Source: SketchFab.

The team released the recreations as downloadable open-source models, thus allowing viewership and most importantly, a sense of liberation and ownership of the Bronzes.

Another example of this digital liberation can be seen in the instance of the Nefertiti Hack. Artists Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles released 3D digital scans of the bust of Nefertiti that was stolen from Egypt by German excavators in the early 1900s. The bust was hidden away for years, only being displayed to German audiences. After making countless requests for the bust to be returned, Egypt was told that “She is and remains the ambassador of Egypt in Berlin” In fact, even though the Neus Museum had 3D scans of the work, they were not permitted to be viewed by the public. Al-Badri and Nelles thus released the 3D scans to the public with a Creative Commons Zero license, completely opening access to the scans (Figure 10).

Figure 10: A view of the 3D scans of the bust of Nefertiti. Source: SketchFab.

How the scans were released remains a mystery, with Al-Badri stating, “Maybe it was a server hack, a copy scan, an inside job, the cleaner, a hoax. It can be all of this, it can be everything.” The artist pair built onto this Nefertit Hack and developed the NefertitiBot, a chatbot with the intention of taking back the interpretation narrative of objects away from museums. The artist pair encourage the bot to be used in museum installations to spark interaction and have the object tell its own story.

Al-Badri similarly brought attention to issues in repatriation and stolen histories through her work, Babylonian Visions. Similar to Anadol, Al-Badri trained a neural network utilizing using GAN technology to create entirely new objects based on ancestral works from Mesopotamian, Neo-Sumerian, and Assyrian artifacts (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Babylonian Vision, art created by GAN technology. Source: EPFL Pavilion.

Out of 5 museums she requested permission from, only the Met and the CMA had APIs that were easy and clear to how could she use the photos. For the other three, Al-Badri utilized web-scraping to download needed images, adding “They don’t understand their digital collections. They also probably don’t understand AI.”

Babylonian Visions, in addition to Casting Memories, Nefertiti Hack, and Nefertiti Bot, emphasize a key theme in artists leveraging Open Access collections to raise critical issues about the role of museums. The works questions how museums address (or do not address) these controversial pasts as they share more objects. While Open Access continues to add more objects to the public domain, critical issues still remain in the ownership of these objects and which museums share their collections. Regarding these various projects, it is important to note that Casting Memories grew from a collaboration with the Smithsonian, Al-Badri and Nelles encourage museums to include Nefertiti Bot in exhibitions, and Babylonian Visions credits the Met and CMA collections. So, while these artists address critical issues, they include museums in the discussion.

Changing Roles: Museums & Open Access

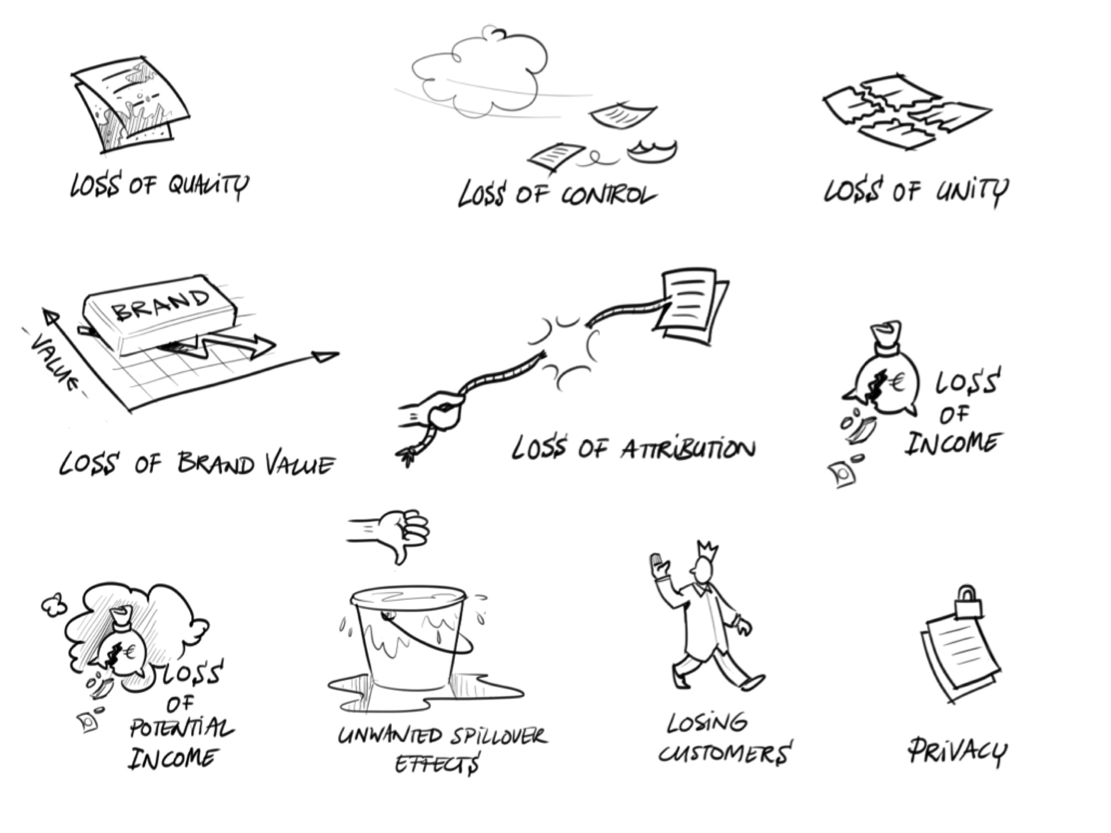

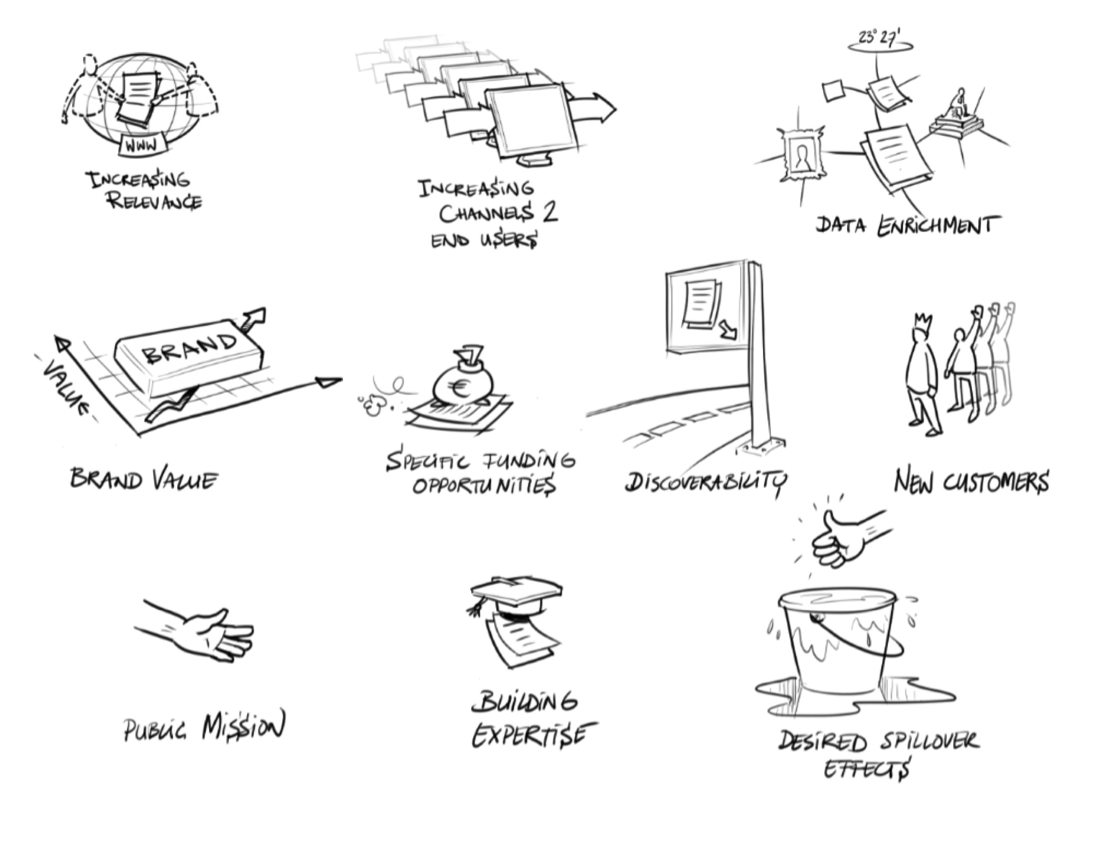

In 2011, Europeana released a white paper, The Problem of the Yellow Milkmaid on open metadata that covered benefits and risks based on workshops with cultural institutions at the time. Nearly ten years since, these risks and benefits are still relevant regarding the Open Access movement.

Figure 12: The perceived risks of open data. Source: MW2013.

Figure 13: The perceived benefits of open data. Source: MW2013.

While museums must face these risks in moving to Open Access, many other museums see Open Access as serving the mission, with the CMA director adding, “The CMA’s Open Access program brings our mission ‘for the benefit of all the people forever’ into the digital age.” The CMA additionally believes that sharing the images will only increase the desire for views to see the works in person, addressing the risk of less patrons with shared collections. Similarly, Effie Kapsalis, Senior Digital Officer at the Smithsonian, created the following video based on her report, the Impact of Open Access on Galleries, Libraries, Museums, & Archives, that highlights the benefits and impact of Open Access, including how institutions have gained new partners, received additional funding, and increased their relevancy.

Figure 14: Give it Away to Get Rich, 2016. Effie Kapsalis. Source: Creative Commons.

While open access still requires a nuanced approach to rights and reproduction policies and how items with significant heritage and culture are shared, it begins to address the complex role museums have played in society and how that role is beginning to shift in the 21st century. While museums grapple with their current role in society and as funding for museums and collection, preservation continues to shift and be questioned, Open Access grants museums the chance to further engage with the public and serve their mission. As UNESCO recommends,

“The provision of public access is the visible evidence of a memory institution’s validity and usefulness to society. It is the justification of public expenditure on preservation, because preservation without the intent of accessibility is pointless.”

While financial estimates of the impact of open access collections still vary, the impact can clearly be seen in the creative works and trailblazing projects of those who utilize them.

+ Resources

“5.2 Opportunities and Challenges of Open GLAM.” Creative Commons. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/chapter/5-2-challenges-and-opportunities-of-open-glam/.

“About.” Amy Karle, March 22, 2021. https://www.amykarle.com/about/.

“About.” MARBLE. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://innovation.library.nd.edu/marble/.

“About.” Refik Anadol, December 7, 2021. https://refikanadol.com/about/?i=d.

“About the Collection.” Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/neues-museum/collections-research/about-the-collection/.

“ArtEcho.” Cooper Hewitt. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://asoa.cooperhewitt.org/artecho/.

“Artist Amy Karle & The Smithsonian Institution Collaboration.” Amy Karle, March 3, 2020.

https://www.amykarle.com/project/_smithsonian_collaboration/.

Belice Baltussen, Lotte, Johan Oomen, Maarten Brinkerink, Maarten Zeinstra, and Nikki Timmermans. “Open Culture Data: Opening GLAM Data Bottom-Up.” MW2013, 2013. https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/open-culture-data-opening-glam-data-bottom-up/.

Birmingham Museums. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/.

Bond, Sarah E. “What the ‘Nefertiti Hack’ Tells Us about Digital Colonialism.” Hyperallergic,

August 4, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/647998/what-the-nefertiti-hack-tells-us-about-digital-colonialism/.

“Casting Memories.” Cooper Hewitt. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://asoa.cooperhewitt.org/castingmemories/#gallery.

“Creative Direction - CMA + AG.” Jess Williams, January 2019.

https://cargocollective.com/JessicaDonofrioWilliams.

Culbertson, Joy. “Top 10 Apis for Museums.” ProgrammableWeb, December 30, 2020. https://www.programmableweb.com/news/top-10-apis-museums/brief/2020/12/26#:~:text=The%20Smithsonian%20Institution%20Open%20Access%20API%20Track%20this,metrics%20about%20objects.%20Search%20by%20category%20or%20terms.

“Digitising All of the Natural History Museum's Collections Could Create Immense Global Societal Benefit – with Economic Value of More than £2bn.” Natural History Museum, October 26, 2021. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/press-office/press-releases/natural-history-museum-frontier-economics-ltd-collections-digitisation.html.

Fisher, Alise. “Smithsonian Releases 2.8 Million Free Images for Broader Public Use.”

Smithsonian Institution, February 25, 2020. https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/smithsonian-releases-28-million-free-images-broader-public-use.

“Generative Adversarial Network (GAN).” GeeksforGeeks, January 15, 2019. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/generative-adversarial-network-gan/#:~:text=Generative%20Adversarial%20Networks%20%28GANs%29%20can%20be%20broken%20down,the%20artificial%20intelligence%20%28AI%29%20algorithms%20for%20training%20purpose.

“Getty Vocabularies.” Getty Vocabularies (Getty Research Institute). Accessed December

3,2021. http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/index.html.

“(In)Visible Artifacts: Parsons Students Explore the Smithsonian Collections with Online Data Visualization Projects.” Smithsonian Institution, February 25, 2021. https://www.si.edu/openaccess/updates/parsons-visualizations.

Kononow, Piotr. “What Is Metadata.” Dataedo, September 16, 2018. https://dataedo.com/kb/data-glossary/what-is-metadata.

Litt, Steven. “Cleveland Museum of Art Launches next-Generation Open Access to Artworks

and Data Online.” cleveland.com, January 24, 2019. https://www.cleveland.com/life-and-culture/g66l-2019/01/fe82a74cbf1054/cleveland-museum-of-art-launches-nextgeneration-open-access-to-artworks-and-data-online-.html.

McCarthy, Douglas. “Licensing Policy and Practice in Open Glam.” Medium. Open GLAM, November 14, 2020. https://medium.com/open-glam/licensing-policy-and-practice-in-open-glam-49c867b49de8.

McCarthy, Douglas. “Open Access and Art History in the 21st Century: The Case for Open GLAM.” CODART, February 12, 2021. https://www.codart.nl/feature/museum-affairs/open-access-art-history-and-the-21st-century-museum/.

McCarthy, Douglas. “Uncovering the Global Picture of Open Glam.” Medium. Open GLAM, November 14, 2020. https://medium.com/open-glam/uncovering-the-global-picture-of-open-glam-af364aadeeee.

McKenzie, Cameron. “What Is Open API (Public Api)?” SearchAppArchitecture. TechTarget, October 13, 2021. https://searchapparchitecture.techtarget.com/definition/open-API-public-API.

“Modern Dream: How Refik Anadol Is Using Machine Learning and Nfts to Interpret Moma's Collection: Magazine: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, November 15, 2021. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/658.

Notaro Schreiber, Kelly. “The Cleveland Museum of Art Advances Open Access Movement.” Cleveland Museum of Art, January 23, 2019. https://www.clevelandart.org/about/press/media-kit/cleveland-museum-art-advances-open-access-movement.

“Open Access FAQs.” Cleveland Museum of Art, February 22, 2021. https://www.clevelandart.org/open-access-faqs.

Paqua, Megan. “Beyond Digitization: Planning for Open Access Collections.” Medium. Pratt

Institute, November 6, 2018. https://museumsdigitalculture.prattsi.org/beyond-digitization-planning-for-open-access-collections-fb7325163f5d.

Scott, Tamara. “How to Use an API: Just the Basics.” TechnologyAdvice, November 12, 2021. https://technologyadvice.com/blog/information-technology/how-to-use-an-api/.

“Smithsonian Institution Enterprise Data Access Network + Open Access Initiative Content Repository.” Smithsonian Institution EDAN Services. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://edan.si.edu/openaccess/docs/.

Snow, Jackie. “These Historical Artefacts Are Totally Faked.” WIRED UK, October 24, 2021. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/fake-artefacts-ai.

Tallon, Loic. “Introducing Open Access at the Met.” The Met, February 7,

“Twilight in the Wilderness.” Cleveland Museum of Art, October 21, 2021. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1965.233.

“Virtual CMA Dashboards.” Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed October 22,

Voon, Claire. “Could the Nefertiti Scan Be a Hoax - and Does That Matter?” Hyperallergic, March 31, 2016. https://hyperallergic.com/281739/could-the-nefertiti-scan-be-a-hoax-and-does-that-matter/.

“What Is an API? (Application Programming Interface).” MuleSoft. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.mulesoft.com/resources/api/what-is-an-api.

“What Is Metadata?” Harvard Law School. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://hls.harvard.edu/dept/its/what-is-metadata/.

“What Is Open Access?” GLAM 3D. Accessed October 21, 2021.

“What We Do.” Creative Commons, August 27, 2020. https://creativecommons.org/about/.