Heading into 2019, we find ourselves on the precipice of what some call Web 3.0 with other technologies extending far beyond the web. Technological change is advancing at quantum speed, with notable innovations likely to impact arts institutions significantly. Arts institutions world-wide continue to use 1st generation technologies for presence and engagement on the World Wide Web. When integrated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, these solutions were massive disruptions for business operations. Critical 1st gen tech, such as email, databases and websites, were tools that expanded institution operations internally and externally for communication and exchange with the world. Today almost every museum has a digital database of artwork, and nearly all nonprofit arts institutions are in the middle of their end-of-year email fundraising campaign.

Second generation (Web 2.0) technologies such as Facebook, Twitter, WeChat, and podcasting have similarly altered the daily operations of the arts management workload around the globe. The following 8 emerging technologies are already disrupting some institutions, but are primed to explode in the near future. Curiously, none of these solutions are new technology per se, but they have simply reached a tipping point of accessibility and affordability thereby catapulting them into the marketplace for users and institutions. Some innovations are mostly behind the scenes, for instance blockchain, while others are more active in the artistic and public spheres, like augmented reality and virtual reality. When encountering ‘emerging technologies’ it is important to note that whatever is accounted for today may not be true in a year. Regardless, a savvy arts manager should be aware of how institutions can, or will be incorporating these technologies in order to be relevant in their communities and among their peers.

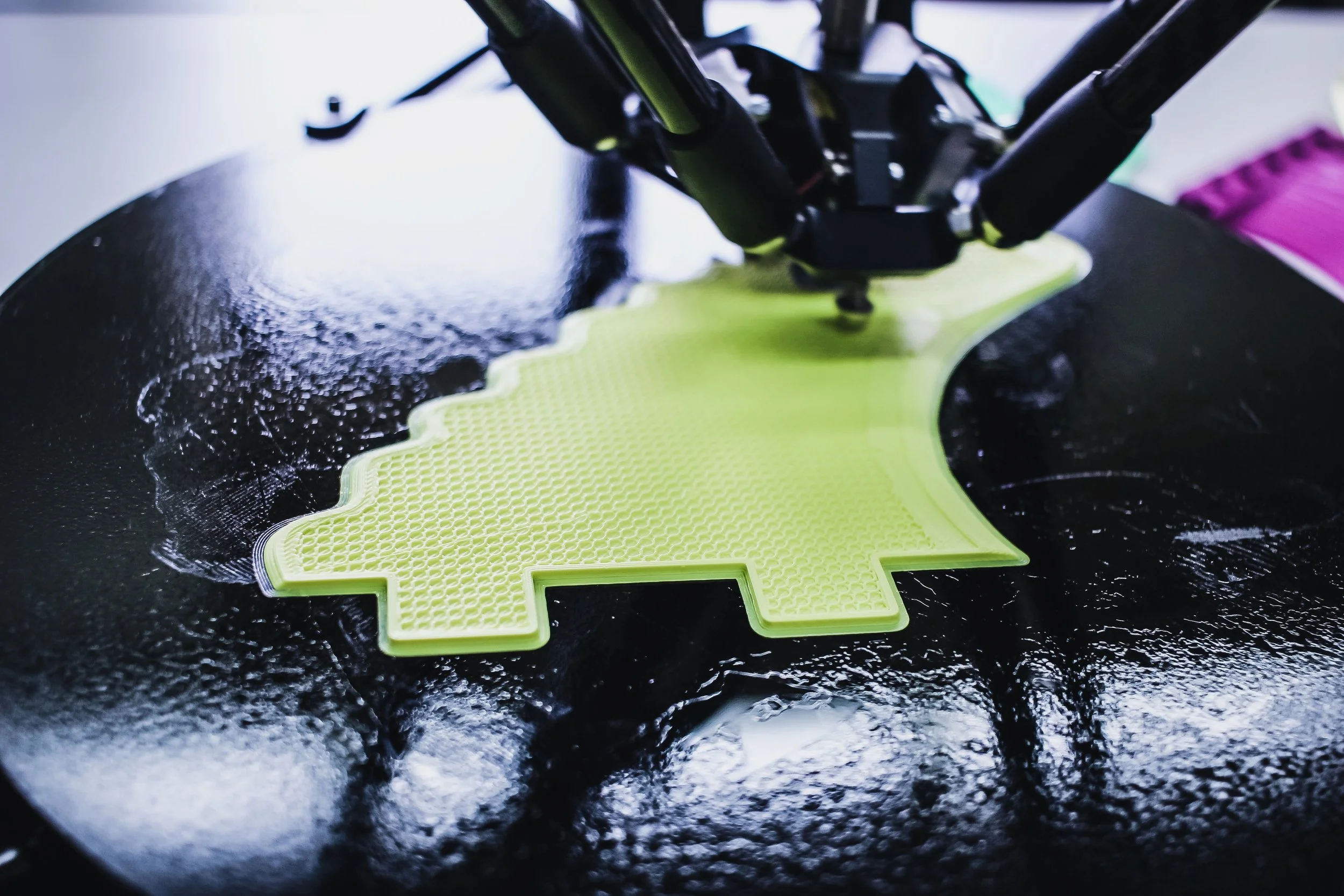

3D PRINTING

3D printing is an excellent example of something that is not a new technology, per se, but is now financially accessible to arts institutions and individuals for use. 3D printing is a manufacturing process by which a computer program controls an additive process for creating a 3-dimensional object. The most common materials for public use are plastics and resins, although titanium and other metals are also possible.

The uses of 3D printing in museums are vast, but most discussions cover the uses of 3D printing for accessibility and education programming. Museums, like the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, use 3D printed objects for touch tours. Similarly, education programs can use 3D reconstructions of existing arts objects to help students understand process and structures. On a larger scale, entire exhibits may be created using 3D technology for reconstruction to allow for education about historical objects or sites.

In the performing arts, 3-D printing is used in creation of stage properties, and Instructables even has code for creating 3-D instruments.

BLOCKCHAIN

Blockchain is a newer technology and its potential uses in the arts and cultural space are expanding. Simply stated, blockchain is a permanent, digital ledger. Blockchain gained international awareness through one blockchain solution: Bitcoin. But Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies are not the same as blockchain, they are simply an easily understood implementation of blockchain as a ledger-form, natural framework for any form of currency. The technology processes running a blockchain are, however, more complex than just a ‘digital ledger’.

Applications for the arts, however, are emerging quickly. Blockchain’s easiest application for the arts is in its value for tracking ownership and use of art objects — a digital framework for maintaining provenance on a material art work, for example, or for tracking digital sales for a song. Blockchain for contracts is also an emerging area of use for larger institutions. Emerging uses for blockchain are explained in a recent article by Jenee Iyer while specific implications for cryptocurrencies in museums is the focus of a recent blog post by Cuseum.

AUGMENTED, VIRTUAL & MIXED REALITY

Augmented reality, virtual reality and mixed reality are different solutions for those searching for an interactive digital experience. Museums and artists are actively using these solutions, creating in house AR or VR experiences or through apps created by vendors.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Augmented_reality_at_Museu_de_Matar%C3%B3_linking_to_Catalan_Wikipedia_(24).JPG

Augmented reality offerings layer over what an individual is seeing through a device. That layer could be a Pokémon, or it could be a text explanation of how mummification worked in ancient Egypt. Augmented reality typically requires an application (app) on a phone or tablet to be used in order for the individual to see the extra layer of information. Augmented reality triggers can be GPS points or images viewed through the lens of the camera on the device.

Articles, conferences and workshops focusing on how museums and performing arts institutions can best utilize augmented reality are common with expansion in the field due to last year’s release of free coding solutions for various device platforms (ARkit, ARcore, etx). The barriers to designing an AR experience lower as access for both design and use can be via the web (arbrowser.io). Examples of AR in museums abound, but leading experiences have been documented at the Detroit Institute for the Arts, the British Museum, and many more.

Artists using AR are increasing. Apps are often required and Rebekah Geiselman detailed how artists are increasingly utilizing AR apps for aesthetic expression. As more artists are working with AR, contemporary museums will have to consider the best way to collect and share this form of digital art.

Virtual reality, while available via browser or simple interfaces like Google Cardboard, provides an individual view within a particular. Again, an app or interface is required for use. Furthermore, it is typically a solo experience (one person, one headset), although that is changing quickly as designers are creating ways in which multiple people can share in a virtual reality experience. Artists are increasingly using this form of visual storytelling, allowing for a perceptively immersive event like Carne Y Arena. Performing Arts organizations such as orchestras are beginning to experiment with using VR as a path for future audience development as demonstrated by Esa Pekka Salonen with the Philharmonia’s recent experiment.

Unlike AR, in which there is a device between the individual and the image in a shared and often open space, VR’s immersion is noted for its need for safety precautions. VR experiences can create nausea and, if moving is encouraged or implied, users can lose their balance or simply walk into obstacles as they navigate the virtual space.

Implementers be warned: audiences are just getting used to these interfaces. Hence, providing clear instructions and, at times, guided support for exhibits using VR and AR experiences is required. Both technologies require specific behaviors to navigate apps or devices appropriately to encounter the arts experience. As museums move into incorporating more of these solutions for either user discovery (AR) or artist projects (VR) staffing and technology challenges will continue to emerge.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE / MACHINE LEARNING

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are not identical but linked technologies used for different outcomes. Applied artificial intelligence as currently implemented utilizes programs to accomplish tasks in a way that mimics human decision-making processes. For example, trading stocks or autonomous vehicles.

Machine learning is a subset of AI in which machines are collecting data by which the machine learns on its own. The concept was credited to a computer scientist in 1959 who twisted the concept of teaching computers everything humans know in order to accomplish tasks to allowing computers to learn on their own. AI is used in our everyday lives from our spam filters in our email to our preference lists on various entertainment channels. AI is also becoming common through uses with chatbots on websites or social media that allow for instant answers for common questions. But there are more deliberate applications in the museum space.

A recent Microsoft app, Seeing AI, utilizes this technology. The app is a tool that low-vision visitors could use in museums to not just navigate space and people but to investigate art. At the Pinacotech Museum in São Paulo an IBM Watson solution allows visitors to query 7 different art works on any question the guest wishes, and the technology will respond with a more personalized answer. A different solution with IBM Watson uses AI to query users during an experience of an exhibition in order to determine perceptions and positions on the Anthropocene. The individual’s results were shared with the individual via a digital visualization of the patron’s responses in comparison to their peers (in the museum and around the world).

It is important to note, however, that as in all things tech, machine learning comes with built in biases of its human programmers. Our machines are only as smart as the data provided, which is often skewed due to availability. The ubiquity of AI in our everyday operations has already been slowed with many companies pulling away from automated solutions until data biases can be removed.

DATA VISUALIZATION

The use of data analytics, whether using big data or internal information, is an almost common concept in society as we move into the 4th industrial revolution fueled by the computer - age. What has changed in recent years is an understanding of the importance of data visualization and the need to finds ways to communicate new discoveries of data using visual techniques. Whether communicating to staff, leadership, funders, artists or your community, learning how to visualize data truthfully and effectively is increasingly critical to an organization’s success.

A leader in the space of data visualization is Albert Cairo who has written several articles and books on the subject and provides resources free to the public. See http://www.thefunctionalart.com/ . Visualization requires recognition that data doesn’t say anything on its own, but you need to work with questions and results to tell a story. Gillian Kim’s work provides and understanding of how to think through a visualization to best convey ideas.

Data analysis and visualization tools are often left to specialists, but powerful tools are entering the marketplace. Open source solutions are available in R while private companies are offering public solutions, like Tableau.

CYBER SECURITY

Security on the web has become increasingly complicated. Security of our data and other people’s data is the responsibility of all museums. Understanding how to create a cyber secure museum is critical to operations. Cybersecurity, simply put, is a methodology for protecting the data within your computer systems, from credit cards from sales to patron information. In previous years, a firewall seemed sufficient to the task. In current times, a clear method for encryption of data, dual -authentication for access to private information and a separate system for public Wi-Fi and internal operations are a minimum. It is also critical to recognize that threats to data security come from both external sources and internal sources.

At a recent Museums and the Web conference, Wendy Pryor explained how to protect museum information and assets in a formal presentation (provided here as a paper).

INTERNET OF THINGS (IOT)

The concepts behind IoT are convenience and efficiency. AI powered smart speakers (Google, Amazon, Apple) are some of the hottest products on the consumer market. These tools are increasingly being utilized for conveying information, and for offering purchasing and donation options for arts institutions. Current uses by nonprofits in the US are rare, although increasing. In the future it may be possible for a patron buy a ticket to a museum or artistic performance via an AI device, and, once the ticket is purchased — all linked ‘things’ would respond accordingly, for example, an autonomous vehicle would pick up the patron in time to make the event and query the patron for any pre-orders of food or services at the museum.

But the individual consumer is not the only space for IoT. Smart cities are the focus of cities, states, and researchers across the globe. Where and when a bus will arrive is as important as connecting LED street lights to levels needed due to both natural light and levels of use in the area. The arts, currently, are of limited presence in this discussion as many Smart City initiatives are mainly focused on critical infrastructure. Once, these issues are resolved, however, quality of life will move more centrally into the smart city agenda and museums and all art forms need to be included in the planning.

CONCLUSION

This article is a sampling of what is emerging and available at the close of 2018. Due to the speed by which technologies enter and mature, some of these will become mainstays to our societies in a few years while others may, like video discs, become a moment of inspiration that fueled the next wave. Furthermore, while not all of these technologies will be of use to every institution, a well-versed arts manager must know the options available in order to evaluate which is best for their institution.