Archeologists around the globe are calling for new methodologies to process and optimize mass-information about cultural heritage sites. The use of satellite imagery, advanced radar technology, and geographical information systems provide unprecedented opportunities to aggregate and analyze geographical data. These advancements enable instantaneous monitoring of at-risk sites, impacting how the cultural heritage sector advocates for world heritage and educates stakeholders.

THEN AND NOW

In the late 19th century, archeologists began using aerial photographs to detect changes in cultural heritage locations. Satellite imagery slowly took over, starting with the declassification of Cold War-era satellite imagery in the mid 1990’s and spring-boarded by IKONOS, the first commercially available high-resolution satellite sensor. Today, geographical data sets are more accessible, affordable, and abundant than ever before.

METHODOLOGY

The volume and velocity of data flowing into the archeological field is too great for any one archeologist, or even two or three. Scientists are experimenting with new methodologies, and while specifics vary, there is one area of consensus: a multi-source approach to data verification. For instance, the American School of Oriental Research (ASOR) confirms findings by cross-referencing information from satellite imagery, social media, news outlets, and in-country contacts.

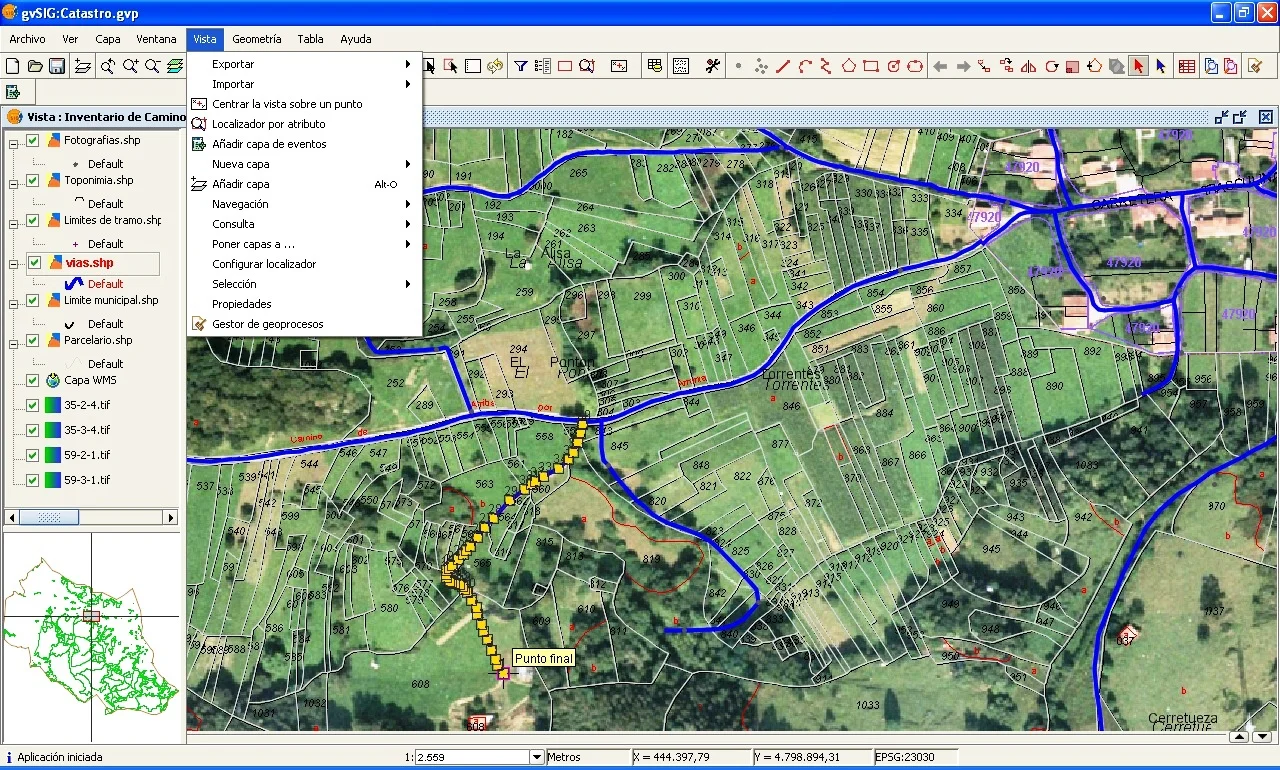

Interface of gvSIG, an open-source, desktop geographical information system. Source: Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GvSIG_-_Geographic_Information_System.jpg

Another experimental methodology touts the benefits of using a computer-automated system (Synthetic Aperture Radar) to track at-risk cultural heritage. Though the use of Synthetic Aperture Radar is both non-destructive and instantaneous, it does not eliminate the need for on-site verification.

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN CRISIS

Geospatial imagery plays an increasingly significant role in monitoring cultural heritage sites in conflict zones. ASOR, funded by the US State Department, uses comparative satellite imagery to track the severity and scope of looting in Syria. They found that looting was not more widespread in ISIS-held areas, but that it was more severe: 42% of ISIS-held cultural sites were identified as moderate to severe instances of looting.

Satellite image of Damascus, Syria by SPOT Satellite Imagery, commercial geographical imagery company. Source: Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Damascus_SPOT_1363.jpg

ASOR also uses geospatial imagery to detect methods used by looters. For example, one of the most damaging methods is the use of heavy machinery to unearth cultural heritage objects. In June of this year, ASOR’s Cultural Heritage Initiative proposed an “automation of change detection analysis”, wherein computers scan hundreds of thousands of satellite images, identify changes, and flag images for analysts attention. ASOR’s findings are used by government agencies, local stakeholders, UNESCO, and other heritage entities to create policies, counter extremism, and support investigations to recover stolen cultural property.

Before and after satellite image of destruction to a Syrian Reactor. 2008. Source: Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Syrian_Reactor_Before_After.jpg

The growing impact of these advancements necessitate a structural shift within the cultural heritage sector. In 2011, Rosa Lasaponara and Nicola Masini state in the Journal of Archaeological Science:

The integration of diverse data sources can strongly improve our capacity to uncover unique and invaluable information, from site discovery to studies focused on the dynamics of human frequentation in relation to environmental changes. This strategic integration requires a strong interaction among archaeologists, scientists and cultural heritage managers to improve traditional approaches [to] archaeological investigation, protection and conservation of archaeological heritage.

There is an emerging opportunity for collaboration, to connect cultural managers, scientists, and archaeologists to make the most of aggregate data and empirical findings. As archaeologists use digital technologies to swiftly identify and track changes in cultural heritage sites, whether due to climate change or war, cultural managers will be able to utilize mass-information to make insightful decisions about education, advocacy, and allocation of resources.

Sources

"Ancient History, Modern Destruction: Assessing the Current Status of Syria’s World Heritage Sites Using High-Resolution Satellite Imagery." American Association for the Advancement of Science. Last modified 2014. Accessed December 2, 2017. https://www.aaas.org/page/Ancient-history-modern-destruction-assessing-current-status-syria-s-world-heritage-sites-using.

Casana, J. "Satellite Imagery-Based Analysis of Archaeological Looting in Syria." Near Eastern Archaeology 78, no. 3 (2015): 142-152.

Cerra, D., S. Plank, V. Lysandrou, J. Tian. “Cultural Heritage Sites in Danger—Towards Automatic Damage Detection from Space.” Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 781. http://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/8/9/781.

Danti, Michael, Scott Branting, Susan Penacho. "The American Schools of Oriental Research Cultural Heritage Initiatives: Monitoring Cultural Heritage in Syria and Northern Iraq by Geospatial Imagery." Geosciences 7, no. 4 (2017): 95.

Deodato Tapete, Francesca Cigna, Daniel N.M. Donoghue, "‘Looting marks’ in space-borne SAR imagery: Measuring rates of archaeological looting in Apamea (Syria) with TerraSAR-X Staring Spotlight, In Remote Sensing of Environment," Volume 178, 2016, Pages 42-58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2016.02.055.

Lyons, J. “Documenting violations of international humanitarian law from space: A critical review of geospatial analysis of satellite imagery during armed conflicts in Gaza (2009), Georgia (2008), and Sri Lanka (2009).” International Review of the Red Cross, 94(886), 739-763.

"Notable & quotable: United nations institute for training and research; hundreds of cultural heritage sites in war-torn Syria have been looted, damaged or even completely destroyed," January 6, 2015. Wall Street Journal. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.cmu.edu/docview/1642427851?accountid=9902.

Lasaponara, Rosa, Nicola Masini. "Satellite remote sensing in archaeology: past, present and future perspectives," Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 38, Issue 9, 2011, Pages 1995-2002, ISSN 0305-4403, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030544031100032X

"Satellite Imagery Helping to Monitor Cultural Heritage Sites under Threat." United Nations Institute for Training and Research. Last modified June 30, 2016. Accessed December 2, 2017. http://www.unitar.org/satellite-imagery-helping-monitor-cultural-heritage-sites-under-threat.