“When you make a decision, you think it’s you doing it, but it’s not. It’s the spirit out there that’s connected to our world that decides what we do and we just have to go along for the ride.”

This is part of Colin’s monologue in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, revealing the film’s theme: while you feel like you are in control, you are actually controlled by others. This is the dilemma of interactive films, which is part of the reason why they are yet to become mainstream in entertainment, especially compared to interactive games.

Colin’s Monologue in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Source: YouTube.

The Dilemma of Interactive Films

As stated in preliminary research, the differences in enjoyment and storytelling models provide the theoretical base to account for the relatively small market interactive films have compared to games. While the audience expects a meaningful “end” to the story due to their eudaemonic motivation, these endings can still cause frustration. This is because the enjoyment they expect from this interactive narrative stems from the enjoyment model of an interactive game, in which the player’s autonomy is essential. If there are a limited number of endings no matter what the player chooses, then the player’s autonomy is compromised. It can even be worse if they watch an interactive movie at a cinema, where the storyline is determined by the majority votes at a decision point. If not fulfilled, this would disrupt people’s immersive experience and lower its pleasure. The major dilemma of interactive film is its conflict between giving the audience freedom of choice and compromising viewers’ real autonomy for the story narrative.

Interactive Films Now

Despite this dilemma, people are curious about this innovative entertainment activity. Since the first interactive movie, Kinoautomat, came out in the 1960s, technology developed for interactive games has advanced to a point where it is able to accomplish a mature interactive movie like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. However, it still does not work as well as interactive games, and here’s why:

There is yet to be a hybrid of film and interactive games

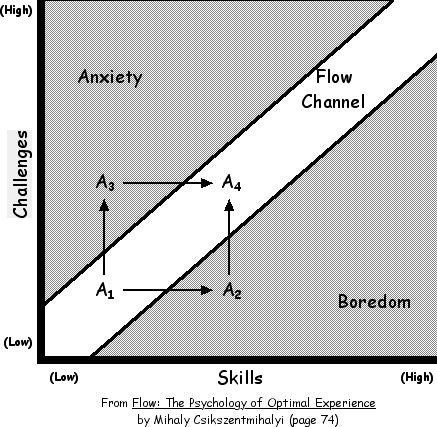

The Flow Theory of Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Source: Medium.

First, one concept should be clear. Interactive films are not a hybrid of traditional film and interactive games due to their deep engagement processes. For traditional films, audiences’ deep engagement is through an unconscious “suture” process. When a shot happens in a film, it implies the presence of an observer outside the film world, i.e. “consciousness,” which is called the Absent One. According to the Suture Theory, the audience will ignore the Absent One as pairs of reverse shots in the film suture this implication of “consciousness.” While the suturing process has expanded from reverse shots, its main idea is that the audience enjoys a film by unconsciously experiencing the narrative from within. For interactive games, audiences’ deep engagement is through repeated frequent interactions. The difference is that this is a conscious process, but the interaction pattern creates flow according to the Flow Theory, which optimizes their engagement.

Interactive films utilize both deep engagement models. The audience cannot remain in the suturing process because making choices breaks the short pair rhythm, which evokes people’s awareness of the Absent One. They cannot remain in the flow process either because the choices appear infrequently compared to the frequent interactions in normal interactive games. Thus, interactive films create a new engagement mechanism. A comparative study of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (interactive film), Late Shift (interactive game/cinema), and Detroit: Become Human (interactive game) will examine the impact of this new narrative style.

Comparison Case Study

Technology

The technology behind Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Source: YouTube.

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch was shot in a normal film set, but its pre/post-production process was revolutionary. The filmmakers initially used the programming software Twine to write the script to coordinate the storyline branches. However, in order to achieve the complexity of a feature film, Netflix developed its own software “Branch Manager” to keep track of all the options and construct the storyline structure. They also developed technologies such as “state tracking” to personalize each viewer’s journey through the subtle impact each choice may have for later scenes.

Even the shooting process becomes unconventional: the actors perform in various different ways for the same scene, and the script supervisor plays a much more essential part on set – not to mention the exceptional amount of devoted time and energy required. This movie has in total around 5 hours of footage for 5 main endings.

App Trailer for Late Shift. Source: YouTube.

CtrlMovie was the developer for Late Shift. CtrlMovie is a full-service toolset. It engages every step throughout the filmmaking process: writing, reading, editing, and platform delivery. Its mobile app allows Late Shift to be released in theaters and film festivals as the audience make their choices through the app, which assigns the next storyline option based on the vote count. It was also released as an interactive game on multiple platforms including PC, PS4, Xbox One, and Switch. The story has 7 different endings.

The technology behind Detroit: Become Human. Source: YouTube.

As an interactive game with a much larger setting and more interactions, Detroit: Become Human uses technology including 3D animations and motion capture. The game makers developed the script for 10 years, which includes more than 2,000 pages of text and 513 characters with their own story. The production has 35,000 different shots and 74,000 unique animations.

Cost

Due to the technological difference in each production, the costs also differ. The budget estimate was approximately 1.5 million dollars for Late Shift, and 30 million dollars for Detroit: Become Human. Due to the nature of Netflix, the budget information for Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is not accessible, but it cost twice as much as planned to produce. What’s more, online articles have disclosed that the rough estimate Netflix spends is between $100 and $250 million per blockbuster movie and between $300 to $500 million per popular TV series. Since Black Mirror was a successful TV series even before the film project launched, it is safe to assume Black Mirror: Bandersnatch was more expensive to produce than Detroit: Become Human to produce.

It is understandable that Late Shift has a much smaller budget, as it was intended to be a small-budget independent film specifically experimenting with this innovative technology. However, if Black Mirror costs more than Detroit: Become Human, it’s likely because of the new software, the extended shooting period, and the budget difference between film sets and animations. That’s another natural disadvantage interactive movies face in comparison to interactive games.

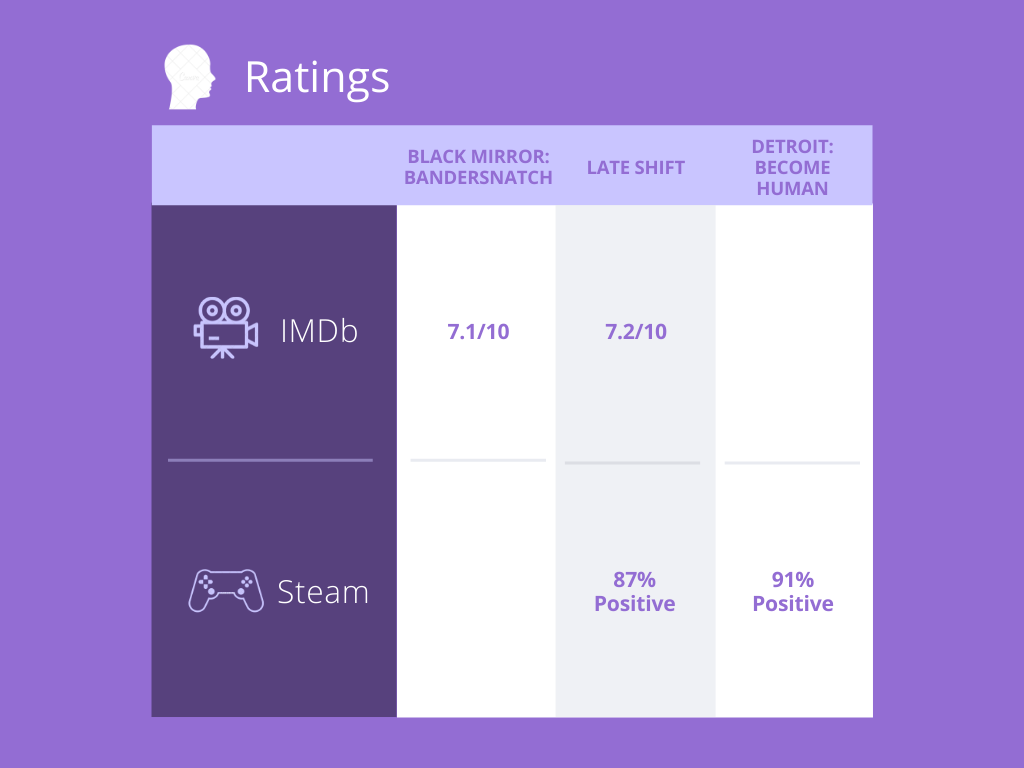

Ratings

Rating Comparison Table. Source: Author.

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch may cost more, but is rated lower than the other two as a game. There is an interesting difference in ratings for Late Shift, which is important to note. Many more people rated Late Shift on Steam, and its rating is much higher when perceived as a game rather than a film.

What’s more, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch earned a relatively high rating because the tact with which filmmakers executed the theme. The creators toy with the idea that you cannot control your fate, even though you think you are able to. This idea is expressed through the audiences who have the opportunity to control the character’s fate through choices. However, through acknowledging the dilemma presented in the plot, the audience receives the “deeper message” they expected from the frustration they may experience.

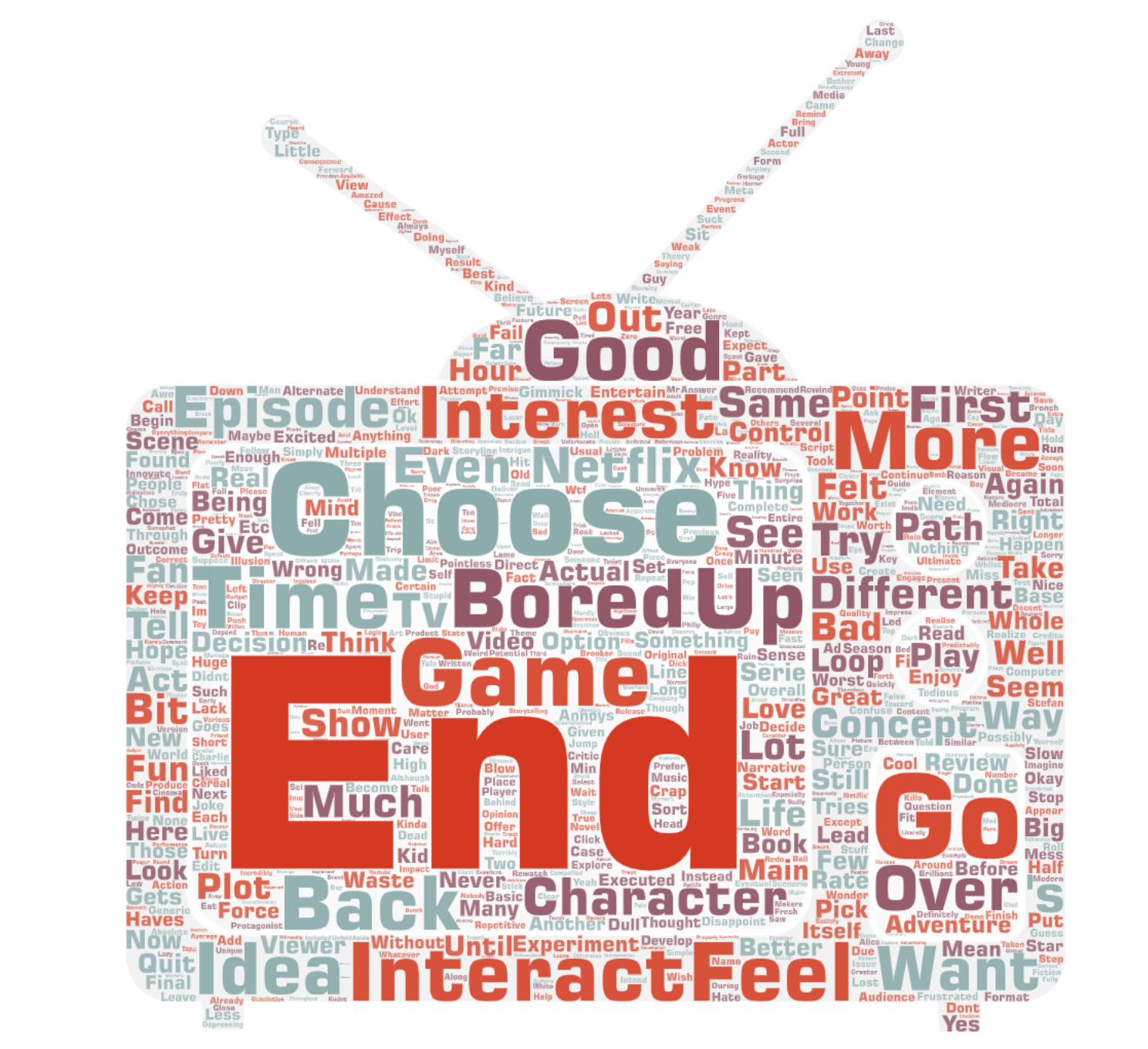

Word Cloud

After scraping more than 5000 online reviews in total for the three productions, here are the word clouds after deleting some of the most frequent, yet “meaningless” words (e.g. “Black” “Mirror” “Bandersnatch”).

Word Cloud Generated from Negative Reviews of Black Mirror Bandersnatch. Source: Author.

Word Cloud Generated from Positive Reviews of Black Mirror Bandersnatch. Source: Author.

One of the top words generated from Black Mirror’s negative reviews is “bored”. While acknowledging the interactive concept was an interesting attempt, most reviews complain about the exhaustion and frustration they experience with the storyline. Among the top voted reviews on IMDb, one reviewer stated, “the executional device (the interactivity) ended up hijacking the story in so far that I was more carried away by the choices I had to make than by the flow of the story itself.” This comment supports the aforementioned theoretical framework.

Word Cloud Generated from Late Shift Reviews as a Film. Source: Author.

Word Cloud Generated from Late Shift Reviews as a Game. Source: Author.

Due to the lack of access to the real theater experience (only in select theaters and film festivals), there are only a few online reviews of Late Shift as a film. However, the struggle is clear when it comes to watching it as a film in a theater. One review article says, “It felt very jarring when my choice was in the minority, and thus the protagonist did the exact opposite of what I wanted.” The UK distributor told the reviewer they just need to come and watch the film again to find out other endings, but the reviewer’s concern becomes: what if the next time the majority of the audience still generates the same storyline? Compared to the reviewers on Steam, the gaming platform, film critics show more concerns about how variability affects the theater audiences’ experience. The article clarified that if someone chooses to enjoy this production as a player rather than a viewer, they will definitely enjoy the story branches more as they get to make choices themselves.

Word Cloud Generated from Detroit: Become Human Reviews. Source: Author.

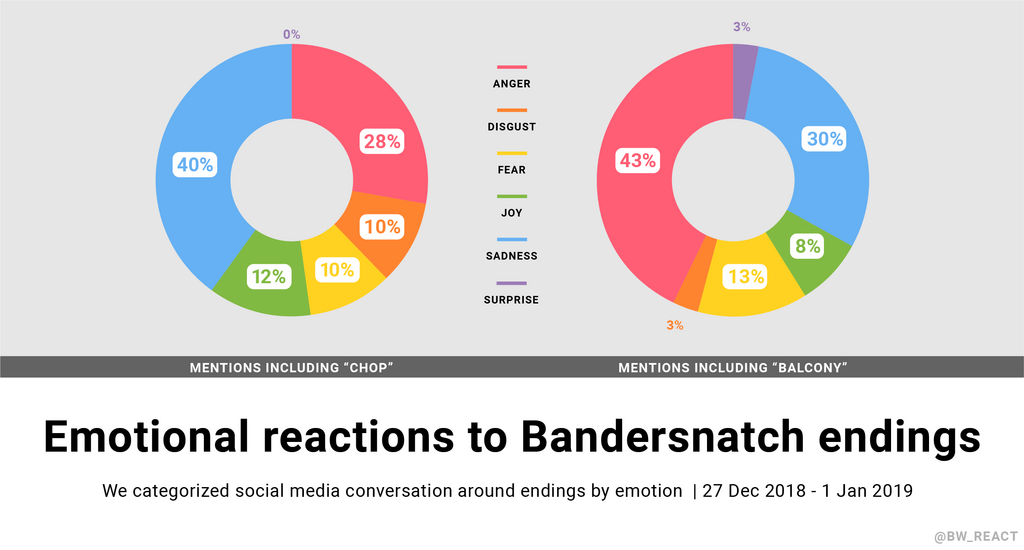

Emotional Reaction to Black Mirror

Emotional Reactions to Bandersnatch Endings. Source: Crowdsourcing a Review of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.

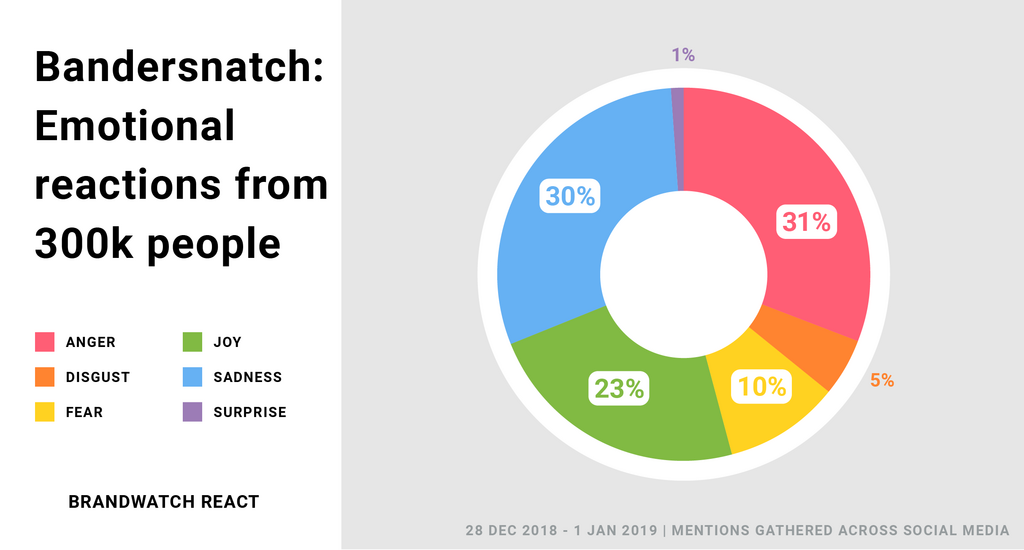

Emotional Reactions to Bandersnatch. Source: Crowdsourcing a Review of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.

Studies have shown that the burden of choice and need for a sense of completion create stress among many viewers of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. The research is supported by this crowdsourced review analysis.

While “joy” only comprises 12% and 8% of the ending-related word mentions, “sadness” comprises 40% and 30%, and “anger” comprises 28% and 43%. When the lens to Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is switched as a whole relating to storyline, the emotional reactions of people’s mentions are 31% anger, 30% sadness, and only 23% joy. Strong emotions expressed by viewers about a story can be a sign of success, but it also displays people’s overwhelming frustration towards the narrative.

Top Used Emojis in Bandersnatch Mentions. Source: Crowdsourcing a Review of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.

Conclusion

As the film industry expands its boundaries by integrating technologies from different fields of entertainment, interactive films are an important topic. Netflix has announced future plans to create more interactive film projects. However, the optimization of the audience experience will be unsuccessful until there is a more comprehensive understanding of engagement patterns and people’s expectations for the interactive film experience. This article attempts to open this discussion by examining theoretical frameworks as well as a comparative case study. As the major concern lies in the disruption of the audience’s engagement, potential future options can be VR or implicit interactions (making choices through the user’s implicit activity) to provide a more engaging process. When the hype for this innovative technology wears off, the core of the films will still be their stories. After all, it’s about storytelling.

+ Resources

Aloyants, Valery. “Detroit: Become Human - The Technology and Creative Process Adopted by Quantic Dream.” Resources 4 Gaming, April 21, 2021. https://www.resources4gaming.com/en/detroit-become-human-the-technology-and-creative-process-adopted-by-quantic-dream.

Anthony, Sebastian. “Late Shift, the World's First Interactive Cinema Movie, Reviewed.” Ars Technica, December 14, 2016. https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2016/12/late-shift-interactive-movie-review/.

“Black Mirror - Bandersnatch (Colin's Speech about the PAC-Man Metaphore).” YouTube. Sjef van Leeuwen, January 1, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3qxWbQ8qek.

Craig, Matthew J., Chad Edwards, and Autumn Edwards. “‘But They’Re My Avatar’: Examining Character Attachment to Android Avatars in Quantic Dream’s Detroit: Become Human.” Companion of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, March 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3371382.3378298.

Desowitz, Bill. “When Netflix's 'Black Mirror: Bandersnatch' Went Interactive, Editing Met Accounting.” IndieWire, May 3, 2019. https://www.indiewire.com/2019/05/black-mirror-bandersnatch-netflix-editing-interactive-1202130943/.

“Detroit: Become Human – Behind the Technology.” YouTube. Quantic Dream, June 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rFgsDvqOIz4.

Farokhmanesh, Megan. “Late Shift Is Another Step toward the Merging of Movies and Video Games.” The Verge, October 15, 2017. https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/15/16360964/late-shift-interactive-movie-films-as-video-games-chady-eli-mattar-interview.

Joyce, Gemma. “Crowdsourcing a Review of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.” Brandwatch, January 2, 2019. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/react-black-mirror-bandersnatch-review/.

Kirke, Alexis. “Why Interactive Films Will Never Work.” Medium, June 26, 2020. https://alexiskirke.medium.com/why-interactive-films-will-never-work-d33b1e8680d3.

Koenitz, Hartmut, Gabriele Ferri, Mads Haahr, Diğdem Sezen, and Tonguç İbrahim Sezen, eds. Interactive Digital Narrative: History, Theory and Practice. London: Routledge, 2017.

“Late Shift – App Trailer – Your Decisions Are You.” YouTube. LATE SHIFT - Your Decisions Are You, February 28, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIw1cGko3fQ.

Linneman, John. “Detroit: Become Human Is a Different Kind of Tech Showcase.” Eurogamer.net, May 24, 2018. https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/digitalfoundry-2018-detroit-become-human-tech-analysis.

Martens, Todd. “The Player: 'Late Shift' Is the First Fully Realized Choose-Your-Own Adventure Movie. or Is It a Game?” Los Angeles Times, April 28, 2016. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/herocomplex/la-ca-hc-the-player-late-shift-20160501-story.html.

McSweeney, Terence, and Stuart Joy. “Change Your Past, Your Present, Your Future? Interactive Narratives and Trauma in Bandersnatch (2018).” Through the Black Mirror, 2019, 271–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19458-1_21.

Mitchell, Alex, Fernández-Vara Clara, and David Thue. Interactive Storytelling: 7th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2014, Singapore, Singapore, November 3-6, 2014: Proceedings. Springer, 2014.

Moltenbrey, Karen. “The Editing and Tech behind Netflix's Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.” postPerspective, May 22, 2019. https://postperspective.com/netflixs-black-mirror-bandersnatch-lets-viewers-choose/.

Nee, Rebecca C. “Wild, Stressful, or Stupid: Que Es Bandersnatch? Exploring User Outcomes of NETFLIX’S Interactive Black Mirror Episode.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 2021, 135485652199655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521996557.

Oliver, Mary Beth, and Arthur A. Raney. “Entertainment as Pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motivations for Entertainment Consumption.” Journal of Communication 61, no. 5 (2011): 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x.

Przybylski, Andrew K., C. Scott Rigby, and Richard M. Ryan. “A Motivational Model of Video Game Engagement.” Review of General Psychology 14, no. 2 (June 2010): 154–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019440.

Schwartz, David I. “Beyond 'Bandersnatch,' the Future of Interactive TV Is Bright.” The Conversation, November 2, 2020. https://theconversation.com/beyond-bandersnatch-the-future-of-interactive-tv-is-bright-111037.

Stokman, Ben. “Movie Review: Late Shift.” Medium. Movie Time Guru, June 19, 2018. https://movietime.guru/late-shift-67efbd06c9c1.

Strause, Jackie. “'Black Mirror' Interactive Film: Inside the 2-Year Journey of 'Bandersnatch'.” The Hollywood Reporter, January 2, 2019. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/black-mirror-bandersnatch-netflixs-interactive-film-explained-1171486/.

Ping, Teng Yong. “Late Shift Review: Cinema Setting Detracts from Game-like Nature of 'Interactive Movie'.” Yahoo!, April 23, 2021. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/late-shift-review-cinema-setting-detracts-game-interactive-movie-094916928.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cub25lLXRhYi5jb20v&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAMM9LoHoc99hsNzat99skl5QDRyavR4HKoFlCXkC2-jrXJwkilN_mVHO17JZr4kO1mzZV849sIHLEnzN5J3Q3sUWHOlIN2MlYGsE-e7U80iHzRLvypFxLMOD234AQ7Hqt51i5HZtFuJzdf9T_Q5x73gY0x7dnUCrT78POvVup-du.

Poe, Arthur S. “How Much Does Netflix Pay for Movies, TV Shows, and Filmmakers?” Fiction Horizon, October 5, 2021. https://fictionhorizon.com/how-much-does-netflix-pay-for-movies-tv-shows-and-filmmakers/.

Prahl, Amanda. “Will Netflix Make More Interactive Movies? Turns out It Already Did!” POPSUGAR Entertainment, January 15, 2019. https://www.popsugar.com/entertainment/More-Interactive-Movies-Netflix-45661713.

Roschke, Ryan. “Blown Away by Black Mirror: Bandersnatch? Wait until You See How They Pulled It Off.” POPSUGAR Entertainment, January 12, 2019. https://www.popsugar.com/entertainment/How-Did-Make-Black-Mirror-Bandersnatch-45637910.

Roth, Christian, and Hartmut Koenitz. “Bandersnatch, Yea or Nay? Reception and User Experience of an Interactive Digital Narrative Video.” Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, June 4, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3317697.3325124.

Tal-Or, Nurit. “The Effects of Co-Viewers on the Viewing Experience.” Communication Theory 31, no. 3 (August 28, 2019). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtz012.

Tanak, Nour. “Interactive Cinema.” MediaLAB Amsterdam, January 2015. https://medialabamsterdam.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/InteractiveCinema_Guideline_v5.pdf.

“Technology.” CtrlMovie. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://ctrlmovie.com/technology.

“User-Submitted Review of ‘Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.’” IMDb, December 29, 2018. https://www.imdb.com/review/rw4543797/?ref_=rw_urv.

Veale, Kevin. “‘Interactive Cinema’ Is an Oxymoron, but May Not Always Be.” Game Studies, September 2012. http://gamestudies.org/1201/articles/veale.

Weiberg, Birk. “Beyond Interactive Cinema.” keyframe.org, August 1, 2002. http://www.keyframe.org/txt/interact/.

Wiberg, Mikael. “Implicit Interaction Design.” ACM Interactions. ACM, February 19, 2014. https://interactions.acm.org/blog/view/implicit-interaction-design.

Willoughby, Ian. “Groundbreaking Czechoslovak Interactive Film System Revived 40 Years Later.” Radio Prague International, June 14, 2007. https://english.radio.cz/groundbreaking-czechoslovak-interactive-film-system-revived-40-years-later-8607007.